Treatment of early heart failure: an ACEI or a β-blocker first?

Transcript of Treatment of early heart failure: an ACEI or a β-blocker first?

Review

10.1517/13543784.15.5.487 © 2006 Informa UK Ltd ISSN 1354-3784 487

Central & Peripheral Nervous Systems

Treatment of early heart failure: an ACEI or a β-blocker first?Ronnie WillenheimerLund University, Department of Clinical Sciences, Malmö, Sweden, and University Hospital, Department of Cardiology, S-205 02 Malmö, Sweden

The basis of modern chronic heart failure (CHF) treatment is a combinationof optimum doses of a β-blocker and an angiotensin-converting enzymeinhibitor (ACEI); however, patients cannot be started on full doses of bothdrugs and treatment has to be initiated one way or the other. By traditionand according to guideline recommendations, an ACEI is usually initiatedfirst, followed by a β-blocker after a varying time period based on clinicaljudgement. Early β-blockade has several theoretical advantages, and twosurrogate end point studies have indicated that initiation of CHF treatmentwith a β-blocker may be superior to an ACEI. The Cardiac Insufficiency Biso-prolol III trial was the first trial investigating the optimum sequence of initi-ating treatment of CHF in terms of mortality and morbidity. The resultsindicated that, in stable, mildly to moderately symptomatic patients withsystolic CHF, initiation of therapy with the β-blocker bisoprolol followed bythe ACEI enalapril was similarly efficacious to the opposite sequence in termsof combined mortality and all-cause hospitalisation. However, initiating ther-apy with bisoprolol showed a trend towards better survival, but also towardsfurther worsening of CHF. This review aims to put these recent findings intoclinical perspective.

Keywords: adrenergic β-antagonists, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, heart failure

Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs (2006) 15(5):487-493

1. Introduction

The current European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heartfailure (CHF) recommend initiating therapy with an angiotensin-convertingenzyme inhibitor (ACEI). After up-titration to its target dose, the ACEI should befollowed by a β-blocker after an unspecified time interval [1]. This recommendationis not based on evidence from clinical studies, but this sequence became the clinicalstandard after ACEIs were shown to improve survival and reduce morbidity in CHFbefore β-blockers were tested [2]. Thereafter, it was commonly considered to beunethical to withhold treatment with an ACEI in CHF patients, and the beneficialeffects on survival and morbidity of β-blockers were shown in addition to a regimenincluding an ACEI [3-5]. The sequence of initiating therapy with an ACEI followedby a β-blocker was – until recently – unchallenged [6,7].

2. β-blocker or ACEI first?

2.1 Theoretical evidenceThere is a good deal of theoretical support for starting CHF treatment with aβ-blocker rather than with an ACEI. In patients with early CHF, the sympatheticsystem is systemically activated at an earlier stage than the renin–angiotensin–aldo-sterone system (RAAS) [8]. β-blockers effectively inhibit the activation of the RAASand sympathetic system, whereas ACEIs predominantly inhibit the RAAS and have

1. Introduction

2. β-blocker or ACEI first?

3. Expert opinion

Exp

ert O

pin.

Inv

estig

. Dru

gs D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Sout

hern

Cal

ifor

nia

on 1

1/09

/14

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

Treatment of early heart failure: an ACEI or a β-blocker first?

488 Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs (2006) 15(5)

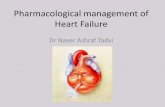

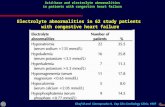

little clinical sympatho-inhibitory effect [9,10]. Sudden deathis the key cause of death in both early CHF (Figure 1) andmildly symptomatic CHF [11-13], and β-blockers have beenconclusively shown to prevent sudden death, whereas ACEIhave not [2-5,14-17]. This evidence alone strongly supportsstarting CHF therapy with a β-blocker rather than with anACEI. In addition, prior studies indicate that β-blockershave a more pronounced effect on survival compared withACEI [2-5], which also supports starting with a β-blocker.Furthermore, although the combination of both classes ofdrugs is recommended as the standard treatment for CHF,the vast majority of patients with CHF do not receive bothagents, especially not in adequate doses [18-20]. The first initi-ated treatment (traditionally an ACEI) is more likely to begiven at its target dose, whereas the second agent (usually aβ-blocker) is often given in suboptimal doses or not atall [18-20]. A likely reason for this undertreatment is a per-ceived problem by physicians and patients, rather than realproblems, as clinical trials generally demonstrate very goodtolerability of β-blockers in patients with CHF. Otherreasons may include insufficient knowledge about the bene-fits of ACEI and, especially, β-blocker treatment in CHF, aswell as logistic difficulties with regards to managing theup-titration of these agents.

2.2 Evidence from ‘surrogate end point’ clinical studiesTwo ‘surrogate end point’ studies support the strategy of initi-ating CHF therapy with a β-blocker first [21,22]. In CARMEN(Carvedilol and ACE-Inhibitor Remodelling Mild Heart Fail-ure Evaluation trial) [21], treatment with the β-blockercarvedilol was at least as effective as the ACEI enalapril interms of the effect on left ventricular volumes on echo-cardiography, whereas the combination group appeared to besuperior. However, the interpretation of this study was con-founded because a large proportion of patients had previouslyreceived an ACEI.

A study by Sliwa et al. [22] compared initiating therapy fornewly diagnosed CHF with carvedilol for 6 months followedby combined therapy with the ACEI perindopril for another6 months, with the opposite treatment order. Most of thepatients were relatively young, black Africans and all hadidiopathic cardiomyopathy as a cause for CHF. Starting withcarvedilol had a superior effect on New York Heart Associa-tion class, left ventricular ejection fraction, plasma N-termi-nal probrain natriuretic peptide concentration and leftventricular volumes.

2.3 CIBIS IIITo date, the CIBIS (Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol) IIItrial has been the first and only mortality/morbidity trialexamining the importance of the order of initiating CHFtherapy comparing the initial strategy of bisoprolol followedby enalapril with the opposite sequence. A large cohort of

1010 patients, of ≥ 65 years of age, with stable, mildly ormoderately symptomatic CHF and a left ventricular ejectionfraction of ≤ 35% were followed up for a mean of 1.2 years.Patients were randomly allocated to initial monotherapywith bisoprolol for 6 months, followed by the addition ofenalapril for ≥ 6 months, or the opposite sequence. The pri-mary objective was to assess non-inferiority for bisoprololfirst versus enalapril first with regard to the primary endpoint of combined mortality or all-cause hospitalisation.CIBIS III essentially showed that it did not matter if therapyfor CHF was started with bisoprolol or enalapril in terms ofcombined mortality and all-cause hospitalisation [7]. Thehazard ratio of bisoprolol first for this combined primaryend point was 0.94 by intention to treat analysis (95% con-fidence interval: 0.77 – 1.16; non-inferiority p = 0.02) and0.97 by per-protocol analysis. Thus the results were quitesimilar with either analysis, although non-inferiority forbisoprolol first was only formally proven by intention totreat analysis, primarily due to issues of statistical power [7].The two approaches also showed similar safety. By design,CIBIS III did not have the statistical power to assess differ-ences between the two treatment strategies in terms of sur-vival [6]; however, the mortality reduction for bisoprolol firstat the end of the 6-month monotherapy phase was 28%(p = 0.24). As all of the patients were followed up for≥ 1 year, the statistical power to detect any differencesbetween the two strategies was greatest at 1 year. For thisreason, a post hoc analysis of the primary end point and itscomponents was performed at 1 year. There were no differ-ences between the two strategies in terms of the combinedprimary end point or with regard to all-cause hospitalisa-tion. However, there was a 31% borderline significant(p = 0.06) mortality reduction for the bisoprolol-firstapproach after 1 year of treatment, and although the mortal-ity differences at the end of the monotherapy phase and at1 year were not statistically significant, they are of similarmagnitude to the 34 – 35% reductions shown for β-blockerscompared with placebo after ∼ 1 year of treatment in themajor β-blocker trials in CHF [3-5]. The importance of sud-den death to these mortality differences in CIBIS III iscurrently being analysed.

In contrast to the effect on survival, bisoprolol first wasassociated with a 25% increase in worsening of CHF events(p = 0.23), either occurring during a hospital stay or causing anew hospitalisation [7]. This was rather expected; althoughβ-blockers have been shown to decrease CHF hospitalisationlong-term [3-5], it is well recognised that initiation andup-titration of a β-blocker may cause minor and temporarydeterioration of CHF [1,23]. This is probably due to an earlyand temporary negative inotropic effect, which might appearto be clinically different in patients who are not receiving abackground ACEI. In clinical practice, this is usually handledby temporarily increasing the diuretic dose, which might havebeen sufficient reason for reporting this as an end point in

Exp

ert O

pin.

Inv

estig

. Dru

gs D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Sout

hern

Cal

ifor

nia

on 1

1/09

/14

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

Willenheimer

Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs (2006) 15(5) 489

CIBIS III patients. However, this finding may not necessarilyindicate that the bisoprolol-first strategy was actuallyassociated with a real risk increase of worsening of CHF com-pared with the enalapril-first approach. The difference inworsening of CHF events could be at least partly explained bythe fact that more patients survived in the bisoprolol-firstgroup, especially during the first year, causing more patientsto be at risk of worsening of CHF (i.e., the well-known phe-nomenon of competing risks). The observation that survivalwas borderline significant in favour of bisoprolol first alsocontradicts the fact that the excess of worsening of CHFevents in the bisoprolol-first group were serious.

2.3.1 SubgroupsCIBIS III did not include severely symptomatic CHFpatients or patients with clinical signs of pulmonarycongestion [6,7]. As it is counterintuitive to start treatmentwith a β-blocker in such patients, it may seem reasonable tofollow the current guideline recommendations [1,23] and starttreatment with an ACEI in this patient population. Amongpatients with stable, mildly to moderately symptomatic,systolic CHF, the CIBIS III results do not indicate anysubgroup of patients that would benefit more from eitherstrategy. With one exception, subgroup analysis showedhomogeneity across all of the subgroups [7]. In patients with aleft ventricular ejection fraction of < 28%, bisoprolol firstwas significantly superior to enalapril first. There was a trendin the opposite direction among patients with an ejection

fraction of 28 – 35%; however, with regard to ejectionfraction, this interaction was mainly due to an imbalancebetween the two study groups in non-cardiovascular hospital-isation during the monotherapy phase. Therefore, it isunlikely to be of clinical relevance. The CARMEN study [21]

does not help to select any subgroup of CHF patients thatwould particularly benefit from either strategy. The study bySliwa et al. [22] showed a benefit of a β-blocker-first strategyon ‘surrogate end points’ and predominantly included rela-tively young, black Africans, all of whom had idiopathiccardiomyopathy. In CIBIS III, patients were ≥ 65 years ofage and almost all of the patients had ischaemic heart diseaseand/or hypertension as CHF aetiology, and there was no dif-ference with regard to the primary end point depending onage or CHF aetiology. Consequently, there is no indicationthat age or aetiology matters in this respect.

2.4 Timing of initiationThere are no guideline recommendations or evidence withregard to the optimum timing between reaching the targetdose of the first drug (usually an ACEI) and starting thesecond (usually a β-blocker) [1,23]. Importantly, there are noreports on the efficacy and safety of simultaneously up-titr-ating both drugs, notwithstanding that this procedure issometimes exercised in clinical practice. The 6-month mono-therapy phase in CIBIS III was partly a compromise betweena monotherapy period long enough to have a fair chance ofdiscovering any difference between the two treatment

Figure 1. Early versus late stages of CHF. In the early phase of CHF, most deaths are sudden cardiac deaths, especially related to highsympathetic nervous system activity, whereas the major cause of death in later stages of CHF is progressive CHF death. As not all drugscan be initiated at once, an initial CHF therapy aimed at reducing sudden cardiac death may be advantageous, whereas therapy in laterstages has several purposes, and consists of multiple drugs and devices.CHF: Chronic heart failure.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

1 2 3

Rel

ativ

e co

ntr

ibu

tio

n (

%)

Goal: improve survival Goal: improve symptoms and survival

Time after diagnosis (years)

One drug at a time

Combination of several drugs

Sudden deathProgressive heart failure death

Exp

ert O

pin.

Inv

estig

. Dru

gs D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Sout

hern

Cal

ifor

nia

on 1

1/09

/14

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

Treatment of early heart failure: an ACEI or a β-blocker first?

490 Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs (2006) 15(5)

strategies, and an ethically justified length [6]. However, theaim was to up-titrate bisoprolol slowly in these elderlypatients and give the patients some time to stabilise onmonotherapy before adding enalapril, which justified≤ 6 months of monotherapy before adding enalapril. In orderfor the comparison between the treatment strategies to befair, bisoprolol could not be initiated earlier than after6 months in the enalapril-first group. Therefore, theCIBIS III design does not allow for any conclusions regardingthe optimum time interval between starting the respectivedrugs nor does it constitute a recommendation about timingin clinical practice. Many clinicians probably intend to starttheir patients on the second drug earlier than after 6 months,especially when starting with an ACEI. Nevertheless, surveysshow that most CHF patients never receive a β-blocker inclinical practice, whereas many other patients remain on anACEI for extended periods of time [18-20]. Any recommenda-tion about the time interval between the first and seconddrug has to be based on clinical experience and judgement,rather than evidence.

2.5 ConclusionsThe current European guidelines for the diagnosis and treat-ment of CHF recommend initiating therapy with an ACEI,to which a β-blocker should be added. This recommenda-tion is not based on evidence, but rather on chance. There issubstantial theoretical support for starting therapy with aβ-blocker rather than with an ACEI, and recent clinical evi-dence suggest that it is a least as beneficial to start with aβ-blocker in clinically stable, mild to moderately sympto-matic CHF patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunc-tion. There is no available data indicating that either strategyis more beneficial in certain subgroups of CHF patients.Consequently, the clinician must make the choice based onindividual judgement in each patient. Importantly, recentstudies have shown that β-blockers are (at least) equallyimportant to ACEI in patients with CHF, and β-blockersshould not be withheld from any patient with systolic CHF,unless contraindicated.

3. Expert opinion

3.1 The β-blocker first

In most of the cases, the author believes that the primarytherapeutic goal in the early phase of CHF should beimproved survival, whereas the long-term aim is improvedquality of life, physical function, morbidity and survival,which is feasible with combined therapy with optimum dosesof several drugs and devices (Figure 1). Mortality is high dur-ing the early phase of CHF and the majority of deaths aresudden deaths. β-blockers have been convincingly shown toreduce sudden death in patients with CHF, whereas ACEIshave not. The results of CIBIS III, with a 28% reduction of

mortality for bisoprolol first during the monotherapy phase(p = 0.24) and a 31% reduction of mortality at 1 year(p = 0.06), are in agreement with this, although final data arenot yet available on sudden death in CIBIS III. If the aim oftherapy in the early phase of CHF is to improve survival, this(if anything) would support starting CHF therapy with biso-prolol rather than enalapril in stable patients with mild ormoderate symptoms.

As the current recommendations to start CHF therapywith an ACEI are based on chance rather than evidence, thesituation may be turned the other way around. Ifmortality/morbidity trials in CHF with a β-blocker hadbeen performed before the corresponding ACEI trials, thecurrent guidelines probably would have recommended start-ing CHF therapy with a β-blocker. Based on such an oppo-site recommendation, CIBIS III would have been designedto assess non-inferiority for enalapril first versus bisoprololfirst, rather than the contrary (as in the CIBIS IIIdesign) [6,7]. In CIBIS III, non-inferiority for bisoprolol firstversus enalapril first was considered to be proven if theupper limit of the 95% confidence interval of the hazardratio for the combined primary end point (mortality orall-cause hospitalisation) was < 1.17. Using a definition ofnon-inferiority for enalapril first versus bisoprolol first simi-lar to the one actually applied in CIBIS III (for bisoprololfirst versus enalapril first), CIBIS III does not actually shownon-inferiority for enalapril first versus bisoprolol first: theupper limit of the 95% confidence interval of the hazardratio for enalapril first versus bisoprolol first with regard tothe primary end point is 1.3 by intention to treat, and 1.28by per-protocol analysis. This lack of non-inferiority for thisdrug sequence, in combination with the survival differencetending to favour bisoprolol first, would most likely havestrengthened the recommendation to start with a β-blocker(which would have prevailed in this scenario). One mightargue that the trend towards a benefit of enalapril first withregard to worsening of CHF events would support startingwith an ACEI; however, this difference may, at least partly,be explained by the survival benefit of the bisoprolol-firststrategy. Furthermore, this difference is likely to have beensmaller if investigators had been accustomed to startingCHF therapy with a β-blocker (as they would have in thisimaginary scenario). In addition, based on clinicalexperience, it is the author’s sincere belief that patients withstable, mild to moderate CHF are generally willing to paythe price of some worsening of CHF to improve the chanceof surviving to a later stage, when symptoms and quality oflife can be improved by multiple combinations of CHFdrugs and devices.

3.2 β-blockers in hypertension versus CHF

Lately, in hypertension, both the ASCOT (Anglo-ScandinavianCardiac Outcomes Trial) [24] and LIFE (Losartan Intervention

Exp

ert O

pin.

Inv

estig

. Dru

gs D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Sout

hern

Cal

ifor

nia

on 1

1/09

/14

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

Willenheimer

Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs (2006) 15(5) 491

For Endpoint) [25] trials have indicated that a β-blocker (i.e.,atenolol) in combination with a thiazide may be inferior to anACEI (i.e., perindopril) in combination with a Ca2+ channelblocker (i.e., amlodipine) or an angiotensin receptor blocker(i.e., losartan) in combination with a thiazide. This does notcontradict a similar or even superior efficacy of bisoprolol com-pared with enalapril in CHF. Hypertension and CHF arepathophysiologically somewhat different manifestations of thecardiovascular continuum; for example, the bloodpressure-lowering effect is very important in hypertension,whereas it may be may be better to effectively antagoniseneurohormonal activation without a significant bloodpressure-lowering effect in CHF. Moreover, different β-block-ers may differ in efficacy; atenolol has been examined in thesehypertension trials, whereas bisoprolol was used in CIBIS III.Furthermore, with reference to the LIFE trial, angiotensinreceptor blockers may be more efficacious than ACEI in hyper-tension and, with reference to ASCOT, amlodipine wasprobably very important to the result. Therefore, the resultsfrom large trials with regard to the efficacy of β-blockers inhypertension may not be at all relevant to the efficacy ofβ-blockers in CHF.

3.3 Up-titration and time interval between drugsThere is presently no rationale for simultaneous up-titrationof a β-blocker and an ACEI. Therefore, the author believesthat the β-blocker and ACEI should be up-titrated one at atime, at least for safety reasons. What is the optimumup-titration schedule and time interval between initiating thefirst and second drug? It might be argued that the mono-therapy phases in CIBIS III were too long, especially the5-month period of monotherapy with the target dose of enal-april. This may well be true, and the author certainly doesnot wait for 5 months before adding a β-blocker when start-ing a CHF patient on an ACEI. However, although oneshould not up-titrate too slowly or wait too long before initi-ating the second agent, it might not be better with a quickup-titration and a short interval between the first and seconddrug. In terms of survival, the non-significant benefit forbisoprolol first versus enalapril first (if anything) was morepronounced at 1 year than at the end of the 6-month mono-therapy phase in CBIS III. Thus, despite the addition of biso-prolol in the enalapril-first group, the mortality benefit forbisoprolol first at the end of the monotherapy phase seemedto increase during the first 6 months of combined therapy.This might be partly due to the fact that, in CIBIS III andclinical practice [19,20], the first initiated agent was lastprescribed at a significantly higher dose than the second

drug [7]. Consequently, if β-blockers are superior to ACEI interms of the survival effect, as indicated by prior findings [2-5],this might be important to short- as well as long-term sur-vival. With a shorter up-titration period and shorter intervalbetween the first and second drugs, it is possible that the dif-ference (with regard to the last prescribed dose) becomes evengreater. Consequently, reaching the optimum dose of theβ-blocker (and ACEI) may be more important than the speedof up-titration and the time interval between the first andsecond drug.

In CIBIS III, patients were 72.5 years of age on average atinclusion [7], and it is especially important to ‘start low and goslow’ in elderly patients. In the typical elderly ambulatoryCHF patient, the author usually up-titrates both an ACEIand a β-blocker with 2- – 4-week intervals. These intervalsmay be shorter if patients are closely monitored. The authoralso generally starts with enalapril 1.25 mg b.i.d. rather thanwith enalapril 2.5 mg (as in CIBIS III). Moreover, the dose ofboth enalapril and bisoprolol is doubled at each titration step,at least for the sake of simplicity. If the patient cannot toleratethe next dose level (e.g., 10 mg), it is possible to try the doselevel in between (e.g., 7.5 mg). Furthermore, in clinically sta-ble, elderly patients with mild to moderate symptoms, theauthor waits for ≥ 4 – 8 weeks after reaching the target dose ofthe first agent before starting the second drug. Consequently,whether starting with bisoprolol or enalapril, up-titrating thefirst agent with 4-week intervals would lead to the initiationof the second drug at 16 – 20 weeks after starting with thefirst one, compared with 26 weeks in the CIBIS III trial. It isimportant to repeatedly reassess the maximum-tolerated doseof both the β-blocker and ACEI in patients who have notreached target doses.

3.4 ConclusionsIn clinically stable CHF patients, there is now an evi-dence-based choice to start antineurohormonal treatmentwith bisoprolol or enalapril. Although it may intuitively seemespecially appealing to start CHF therapy with a β-blocker inpatients with ischaemic heart disease and/or tachycardia, thereis no available data indicating that either strategy is more ben-eficial in certain subgroups of CHF patients. However, theauthor considers a bisoprolol-first strategy to be an attractivechoice in almost all clinically stable patients with systolicCHF and mild or moderate symptoms. Last but not least,CIBIS III has taught clinicians that β-blockers are at leastequally important to ACEIs in patients with CHF. Unlesscontraindicated, β-blockers should not be withheld from anypatient with systolic CHF.

Exp

ert O

pin.

Inv

estig

. Dru

gs D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Sout

hern

Cal

ifor

nia

on 1

1/09

/14

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

Treatment of early heart failure: an ACEI or a β-blocker first?

492 Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs (2006) 15(5)

BibliographyPapers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

1. SWEDBERG K, CLELAND J, DARGIE H et al.: Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology: guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure: executive summary (update 2005). Eur. Heart J. (2005) 26:1115-1140.

•• Updated European guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of CHF.

2. GARG R, YUSUF S: Overview of randomized trials of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. Collaborative Group on ACE Inhibitor Trials. J. Am. Med. Assoc. (1995) 273:1450-1456.

• Overview of randomised trials of ACEIs on mortality and morbidity in patients with CHF.

3. CIBIS II INVESTIGATORS AND COMMITTEES: The Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study II (CIBIS II): a randomized trial. Lancet (1999) 353:9-13.

• Pivotal trial about the effects of β-blockade on mortality and morbidity in patients with CHF.

4. MERIT-HF STUDY GROUP: Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: metoprolol CR/XL randomized intervention trial in congestive heart failure (MERIT-HF). Lancet (1999) 353:2001-2007.

• Pivotal trial about the effects of β-blockade on mortality and morbidity in patients with CHF.

5. PACKER M, COATS AJ, FOWLER MB et al.: Carvedilol Prospective Randomized Cumulative Survival Study Group: effect of carvedilol on survival in severe chronic heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. (2001) 344:1651-1658.

• Pivotal trial about the effects of β-blockade on mortality and morbidity in patients with CHF.

6. WILLENHEIMER R, ERDMANN E, FOLLATH F et al.: on behalf of the CIBIS-III investigators: Comparison of treatment initiation with bisoprolol versus enalapril in chronic heart failure patients: rationale and design of CIBIS-III. Eur. J. Heart Fail. (2004) 6:493-500.

7. WILLENHEIMER R, VAN VELDHUISEN DJ, SILKE B et al.: On behalf of the CIBIS-III investigators. Effect on survival and hospitalization of initiating treatment for chronic heart failure with bisoprolol followed by enalapril, as compared with the opposite sequence. Results of the Randomized Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study (CIBIS) III. Circulation (2005) 112:2426-2435.

• Pivotal trial about the effects on mortality and morbidity of starting treatment in patients with CHF with β-blockade or ACE inhibition.

8. PACKER M: Pathophysiology of heart failure. Lancet (1992) 340:88-95.

9. CAMPBELL DJ, AGGARWAL A, ESLER M, KAYE D: β-blockers, angiotensin II, and ACE inhibitors in patients with heart failure. Lancet (2001) 358:1609-1610.

10. TEISMAN AC, VAN VELDHUISEN DJ, BOOMSMA F et al.: Chronic βblocker treatment in patients with advanced heart failure. Effects on neurohormones. Int. J. Cardiol. (2000) 73:7-14.

11. URETSKY BF, SHEAHAN RG: Primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in heart failure: will the solution be shocking? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. (1997) 30:1589-1597

12. HUIRKURI HV, CASTELLANOS A, MYERBURG RJ: Sudden death due to cardiac arrhythmias. N. Engl. J. Med. (2001) 345:1473-1482.

13. LANE RE, COWIE MR, CHOW AW: Prediction and prevention of sudden cardiac death in heart failure. Heart (2005) 91:674-680.

14. KRUM H: β-adrenoceptor blockers in chronic heart failure – a review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. (1997) 44:111-118.

15. HEIDENREICH PA, LEE TT, MASSIE BM: Effect of β-blockade on mortality in patients with heart failure: a meta analysis of randomized clinical trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. (1997) 30:27-34.

16. LECHAT P, PACKER M, CHALON S, CUCHERAT M, ARAB T, BOISSEL JP: Clinical effects of β-adrenergic blockade in chronic heart failure. A meta-analysis of double blind, placebo controlled, randomized trials. Circulation (1998) 98:1184-1191.

17. CLELAND JG, MASSIE BM, PACKER M: Sudden death in heart failure: vascular or electrical? Eur. J. Heart Fail. (1999) 1:41-45.

18. DAVIES M, HOBBS F, DAVIS R et al.: Prevalence of left-ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure in the Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening study: a population based study. Lancet (2001) 358:439-444.

19. CLELAND JG, COHEN-SOLAL A, AGUILAR JC et al.: IMPROVEMENT of Heart Failure Programme Committees and Investigators: improvement programme in evaluation and management; Study Group on Diagnosis of the Working Group on Heart Failure of The European Society of Cardiology Management of heart failure in primary care (the IMPROVEMENT of Heart Failure Programme): an international survey. Lancet (2002) 360:1631-1639.

• Important survey on the management of patients with CHF in clinical practice.

20. KOMAJDA M, LAPUERTA P, HERMANS N et al.: Adherence to guidelines is a predictor of outcome in chronic heart failure: the MAHLER survey. Eur. Heart J. (2005) 26:1653-1659.

• Important survey on the adherence to guideline recommendations and management of patients with CHF in clinical practice.

21. REMME WJ, RIEGGER G, HILDEBRANDT P et al.: The benefits of early combination treatment of carvedilol and an ACE-inhibitor in mild heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction. The carvedilol and ACE-inhibitor remodelling mild heart failure evaluation trial (CARMEN). Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. (2004) 18:57-66.

22. SLIWA K, NORTON GR, KONE N et al.: Impact of initiating carvedilol before angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy on cardiac function in newly diagnosed heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. (2004) 44:1825-1830.

23. HUNT SA, BAKER DW, CHIN MH et al.: American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1995 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure); International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation; Heart Failure Society of America: ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult: executive summary A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1995 Guidelines for the Evaluation and

Exp

ert O

pin.

Inv

estig

. Dru

gs D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Sout

hern

Cal

ifor

nia

on 1

1/09

/14

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

Willenheimer

Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs (2006) 15(5) 493

Management of Heart Failure): developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation; endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation (2001) 104:2996-3007.

24. DAHLOF B, SEVER PS, POULTER NR et al.: ASCOT Investigators. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as

required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet (2005) 366:895-906.

25. DAHLOF B, DEVEREUX RB, KJELDSEN SE et al.: LIFE Study Group. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet (2002) 359:995-1003.

AffiliationRonnie Willenheimer1,2 MD, PhD1Associate Professor of Cardiology, Lund University, Department of Clinical Sciences, Malmö, Sweden†2Associate Professor of Cardiology, University Hospital, Department of Cardiology, S-205 02 Malmö, SwedenTel: +46 40 33 1000; Fax: +46 40 33 6209;E-mail: [email protected]

Exp

ert O

pin.

Inv

estig

. Dru

gs D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y U

nive

rsity

of

Sout

hern

Cal

ifor

nia

on 1

1/09

/14

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.