Disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection in a patient carrying autoantibody to...

Transcript of Disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection in a patient carrying autoantibody to...

CASE REPORT

Disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection in a patientcarrying autoantibody to interferon-c

Takashi Ishii • Atsuhisa Tamura • Hirotoshi Matsui •

Hideaki Nagai • Shinobu Akagawa •

Akira Hebisawa • Ken Ohta

Received: 15 December 2012 / Accepted: 7 February 2013 / Published online: 28 February 2013

� Japanese Society of Chemotherapy and The Japanese Association for Infectious Diseases 2013

Abstract A 66-year-old man was admitted to our hospital

on suspicion of lung cancer with bone metastasis. He suf-

fered multiple joint and muscle pain. 18F-Fluorodeoxy

glucose positron emission tomography (FDG–PET)

showed multiple accumulations in the lung, bones includ-

ing the vertebrae, and mediastinal lymph nodes. Anti-

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody was

negative. Because Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC)

was isolated from bronchial lavage fluid, bronchial wall,

peripheral blood, and muscle abscess, he was diagnosed as

having disseminated MAC infection. Although multidrug

chemotherapy was initiated, his condition rapidly deterio-

rated at first. After surgical curettage of the musculoskel-

etal abscess, his condition gradually improved. As for

etiology, we suspected that neutralizing factors against

interferon-gamma (IFN-c) might be present in his serum

because a whole blood IFN-c release assay detected low

IFN-c level even with mitogen stimulation. By further

investigation, autoantibodies to IFN-c were detected, sug-

gesting the cause of severe MAC infection. We should

consider the presence of autoantibodies to IFN-c when a

patient with disseminated NTM infection does not indicate

the presence of HIV infection or other immunosuppressive

condition.

Keywords Disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex

infection � Autoantibody to interferon-c

Introduction

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), including Myco-

bacterium avium complex (MAC), are environmental

microorganisms living widely in soil and water. Infection

with NTM occurs with compromised local or general

immune responses [1]. Although MAC causes pulmonary

infections in patients who have underlying diseases such as

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasis,

pulmonary MAC infection occurs mainly in the form of

middle lobe or lingual segment lesions in middle-aged

women who have apparently no underlying disease [2]. As

for general immune compromise, patients with human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or a malignant

tumor are susceptible to MAC infection, as well as patients

who use anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a) drugs.

These patients might suffer a disseminated type of infec-

tion, especially seen in HIV patients [3].

The interleukin-12-dependent interferon-gamma (IFN-

c) pathway, which is the main regulatory pathway of cell-

mediated immunity, is supposed to have a crucial role in

NTM immunity [4]. Recently, an increasing number of

papers have reported disseminated NTM infection in

patients expressing autoantibodies to IFN-c, especially in

Asian patients [5]. In Japan, there have been two such

reports [6, 7]. Here we report a Japanese man who devel-

oped disseminated MAC infection, presumably caused by

autoantibodies to IFN-c.

Case report

A 66-year-old man was admitted to our hospital on suspicion

of lung cancer with bone metastasis in June 2011. He had

hepatitis C and had been treated with interferon-alpha until

T. Ishii (&) � A. Tamura � H. Matsui � H. Nagai �S. Akagawa � A. Hebisawa � K. Ohta

Department of Respiratory Medicine, Center for Pulmonary

Diseases, National Hospital Organization of Tokyo Hospital,

3-1-1 Takeoka, Kiyose, Tokyo 204-8585, Japan

e-mail: [email protected]

123

J Infect Chemother (2013) 19:1152–1157

DOI 10.1007/s10156-013-0572-2

April 2011. He suffered multiple joint and muscle pain in

June, diagnosed as polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) in another

hospital. Because PMR often accompanies malignant tumors,18F-fluorodeoxy glucose positron emission tomography

(FDG–PET) was performed to reveal multiple accumulations

in the lung, bones including the vertebrae, and mediastinal

lymph nodes. He was then referred to our hospital. He suffered

sudden hearing loss around the same time and had been taking

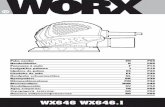

Table 1 Laboratory findings

sIL-2R Soluble interleukin-2

receptor, CCP cyclic

citrullinated peptide

WBC (/ll) 13,300 IgG (mg/dl) 1,339 Acid-fast test

Neu (%) 84 IgM (mg/dl) 116 Sputum

Mon (%) 3 IgE (IU/ml) 523 Smear (±)

Lym (%) 9 CRP (mg/dl) 2.85 Culture (?)

Eos (%) 4 b-D Glucan (pg/ml) \6.0 MAC-TRC (?)

Hb (g/dl) 11.4 HBs-Ag (-) Bronchial lavage fluid

Plt (/ll) 28.7 9 104 HCV-Ab (?) Smear (2?)

ESR (mm/h) 57 HIV-Ab (-) Culture (?)

sIL-2R (U/ml) 4,290 Blood

TP (g/dl) 6.5 CD4 (/ll) 559 Smear (-)

Alb (g/dl) 3.2 CEA (ng/ml) 3.6 Culture (?)

AST (IU/l) 10 Anti-CCP Ab (U/ml) 214 MAC-TRC (?)

ALT (IU/l) 16 RF (IU/ml) 46

LDH (IU/l) 150 HbA1c (%) 7.0

ALP (IU/l) 291 QFT@TB-3G

T-Bil (mg/dl) 0.47 Nil 0.04

Cre (mg/dl) 0.7 E-N 0.01

Na (mEq/l) 137 M-N 0.02

K (mEq/l) 4.4 T-SPOT TB (?)

BNP (pg/ml) 26.6

Fig. 1 a Chest X-ray shows

multiple infiltrates

predominantly in the right lung

field. b Chest computed

tomography (CT) shows

multiple infiltrates in lung fields

and swollen mediastinal lymph

nodes. c Transbronchial biopsy

specimen shows epithelioid cell

granulomas and erosion in

bronchus. Ziehl–Neelsen stain

revealed acid-fast bacilli (not

shown)

J Infect Chemother (2013) 19:1152–1157 1153

123

prednisolone (PSL) 15 mg/day. He complained of moderate

back pain and mild cough and sputum without preceding

weight loss.

On admission, his physical examination revealed low-

grade fever (37.3 �C). As shown in Table 1, laboratory

data revealed elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and

erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), plus hypoalbumi-

nemia. Soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R) level and

anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody titer were

elevated. Hemoglobin A1c was also elevated, although it

had been within normal range several months previously.

Anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody and

anti-human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV)-1 antibody were

negative. Antibody titers against Epstein–Barr virus indi-

cated a postinfection pattern. Mycobacterium avium was

isolated from sputum on admission. No other bacteria were

detected in sputum and blood. Chest X-ray (Fig. 1a)

exhibited multiple infiltrates. Computed tomography (CT)

(Fig. 1b) revealed multiple infiltrates and nodule-like

shadows, mainly in the right lung field, swelling in medi-

astinal lymph nodes, and destruction in the transverse

process of the lumbar vertebrae.

Bronchoscopic examination was performed twice on

suspicion of lung cancer. However, histological examina-

tion of transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) specimens

detected remarkable inflammation and granuloma forma-

tion in the bronchial walls (Fig. 1c), with bronchial lavage

fluid revealing large amounts of Mycobacterium avium. We

also confirmed that Mycobacterium avium was positive in

the peripheral blood culture. He was, therefore, diagnosed

as having disseminated MAC infection. The vertebral

lesion was suspected to be an abscess and osteomyelitis

caused by MAC.

Multidrug therapy by rifampicin (RFP, 450 mg/day),

ethambutol hydrochloride (EB, 750 mg/day), and clarithro-

mycin (CAM, 800 mg/day) was initiated after the second

bronchoscopy. However, his disease was rapidly progressive

and difficult to control, despite the reinforcement of therapy

with amikacin sulfate (AMK, 400 mg/day) and levo-

floxacin hydrate (LVFX, 500 mg/day) or moxifloxacin

hydrochloride (MFLX, 400 mg/day), even after cessation of

the oral PSL.

After a month of treatment, chest X-ray (Fig. 2a), CT

(Fig. 2b), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed

aggravation of lung lesions and multiple musculoskeletal

abscesses in the right clavicle and left iliopsoas muscle.

Because we thought chemotherapy alone was inadequate,

we referred him to an orthopedic surgeon to curette the

abscesses as an additional local treatment. Surgical curet-

tage of the abscess (iliopsoas muscle) and anterior inter-

body fusion were performed about 3 months after the

beginning of the treatment. Mycobacterium avium was

isolated from the abscess.

Disseminated MAC lesions were gradually improved

with continuation of the chemotherapy of RFP, EB, CAM,

and LVFX. Blood and sputum culture of MAC changed to

be negative together with improved inflammatory response

on blood examination. Chest X-ray exhibited improvement

of pulmonary lesions (Fig. 3). He was finally discharged in

March 2012, and so far no relapse of MAC has been

observed.

Fig. 2 a Chest X-ray after

1 week of chemotherapy shows

aggravation of the multiple

infiltrates, especially in the right

lung field. b Abdominal CT

reveals an abscess in the left

iliacus muscle

Fig. 3 Chest X-ray after curettage of abscess and continuation of

chemotherapy shows amelioration of the multiple infiltrates in both

lung fields

1154 J Infect Chemother (2013) 19:1152–1157

123

Although he took PSL on admission, his symptoms

began before the use of PSL, and the disease deteriorated

after he ceased using oral PSL. In addition, anti-HIV and

anti-HTLV-1 antibodies were negative. We suspected the

presence of other conditions of immunodeficiency.

Because the whole blood IFN-c release assay [using

QuantiFERON TB-3G (QFT-3G)] detected a low IFN-clevel even with mitogen stimulation (PSL was already

discontinued at the time), we performed the enzyme-linked

immunosorbent spot for tuberculosis test (T SPOT-TB); it

Table 2 Case reports of non-human immunodeficiency virus (non-HIV) patients with disseminated nontuberculous mycobacterial infection in

Japan since 2000

Age Sex Underlying disease Symptoms Location NTM isolates Treatment Outcomes Year

reported

45 F None Fever/BW loss/

cervical

lymphadenopathy

LNs/BR/

LU/SP/LI/

BO/PL/

SKs

M. intracellare INH/RFP/EB/CAM Improved 2002

63 F None Back pain BOs/LU MAC N.D. N.D. 2003

74 F Hepatitis

C/hypergammaglobulinemia

Fever/back pain LU/BO M. intracellare RFP/EB/

CAM ? CAM/

LVFX/SM

Improved 2008

44 F Anti-IFN-c autoantibody Fever/lumbago BOs/soft

tissue

M. avium RFP/EB/CAM/

LVFX/

SM ? drainage

Improved 2009

76 M DLBCL Dyspnea LNs/BOs M. avium RFP/EB/CAM/SM/

airway stenting/

RT/chemotherapy

for DLBCL

Improved 2010

27 M MDS/sPAP Fever LU/

meninges/

PL/SK

M. abscessus CAM/AMK/

IPM,CS/PBSCT

Died 2009

82 M Prostatic cancer (anti-

androgen therapy)

Fever/back pain/

ear pain

LNs/BR/

LU/LNs/

BOs/SK/

tympanum

M. avium RFP/EB/CAM/SM Improved 2006

54 M Anti-IFN-c autoantibody Fever/BW loss/

cough

LNs/SP/PL/

BOs

MAC RFP/EB/CAM/

SM ? treatment

for S. pyogenes

infection

Improved 2007

65 M Silicosis Fever/back pain LNs/SP/

BOs

M. avium RFP/EB/CAM/SM Improved 2009

81 M Short bowel syndrome,

malnutrition

Consciousness

disturbance/

anorexia

LU/BM M. kansasii N.D. Improved 2005

56 M Sweet’s disease Fever/anemia/

pancytopenia

LU/BL M. avium RFP/EB/CAM/SM Died 2004

64 M MDS N.D. BM/BR Others INH/RFP/EB/CAM Died 2001

61 F CML N.D. BM MAC RFP/EB/CAM/

LVFX

Died 2001

83 F Malignant lymphoma N.D. BM MAC None Died 2003

59 M Hepatitis B virus carrier Skin eruption/leg

swelling

LU/SK M. szulgai INH/RFP/PZA/SM Improved 2011

66 M Chronic hepatitis Lumbago LNs/BR/

LU/BO/

soft tissue

M. avium RFP/EB/CAM/

LVFX/

AMK ? drainage

Improved Present

case

LY lymph node, BR bronchus, LU lung, PL pleura or pleural effusion, SP spleen, LI liver, BM bone marrow, BL blood, BO bone, SK skin, INH

isoniazid, RFP rifampicin, EB ethambutol, CAM clarithromycin, LVFX levofloxacin, IPM/CS imipenem/cilastatin, AMK amikacin, SM strep-

tomycin, PZA pyrazinamide, DLBCL diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, MDS myelodysplastic syndrome, CML chronic myelogenous leukemia,

sPAP secondary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

J Infect Chemother (2013) 19:1152–1157 1155

123

proved to be positive, indicating an IFN-c-neutralizing

factor in the patient’s serum. We sent his whole blood

sample to Niigata University Medical and Dental Hospital

for further investigation. In his blood, no activation of the

IFN-c signal pathway was detected even after a direct IFN-

c stimulation. Then, a high titer of autoantibodies to IFN-cwas identified in his serum using enzyme-linked immu-

nosorbent assay (ELISA) [7].

Discussion

Here we have reported a HIV-negative man who had dis-

seminated NTM infection. It is considered rare in non-

HIV-infected patients [8], although it is on the increase. In

Japan, 16 cases of disseminated NTM patients without HIV

have been reported since 2000, including our case

(Table 2). The mean age was 63 years (range, 27–83

years). Of these 16 patients, 6 had hematological disorders.

Two had long-term steroid or immunosuppressive drug

therapy, and 3 had anti-interferon-gamma autoantibody. As

for mycobacterial species, MAC was the most common

(75 %); Mycobacteria abscessus, Mycobacteria szulgai,

and Mycobacteria kansasii were identified in 1 case each.

The most common organ involvement was bone (60 %).

The prognosis was poor even with chemotherapy and

surgical drainage. In Thailand, M. abscessus is identified

most frequently (48 %), and the most common organ

involved was the lymph nodes (89 %) [5], which differs

from our results.

In our case, the patient seemed to be immunocompetent.

We suspected the patient’s serum included an IFN-c-

neutralizing factor because of the discrepancy between the

results of QFT-3G and T SPOT-TB. T SPOT-TB can

identify the number of effector T cells, white blood cells

that produce IFN-c at the single cell level. Although we

could not specify the reason why his T SPOT-TB test was

positive (perhaps a past Mycobacteria tuberculosis infec-

tion existed), this result means the IFN-c productivity of

the lymphocytes is intact. Logically, the serum must have

included some factors that reduce the titer of IFN-c. The

dissociation between QFT-3G and T SPOT results may be

helpful in screening for autoantibodies to IFN-c.

After the first disseminated NTM infection case with

autoantibodies to IFN-c was reported in 2004 [8], there

have been increasing numbers of similar reports, especially

of Asian patients [5]. Although low titers of autoantibodies

to IFN-c could be observed in healthy people with viral

infection [9], patients with disseminated NTM infection had

high titers of the autoantibodies. Some patients presented

with other autoimmune disorders such as autoimmune

diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and hypogonadism [10].

In our case, the patient had high titers of anti-CCP

antibodies without apparent rheumatoid arthritis. Co-

infection with opportunistic pathogens was often reported,

and some patients had multiple species of NTM infection

[11]. Recurrent and persistent infections also could be seen.

This finding may indicate that the patients with these

autoantibodies are in an immunocompromised state, but

further follow-up of the patients is needed. Treatment with

multiple antibiotics seemed to be effective for NTM

infection, but two cases in Japan (including our case) nee-

ded surgical drainage of the abscess caused by NTM [7]. To

reduce the titer of autoantibodies to IFN-c for the refractory

case, intravenous immunoglobulin demonstrated little effi-

cacy [7]. On the other hand, anti-CD20 therapy reduced the

titer, leading to the improvement of disease control [12].

In conclusion, we have described a case of disseminated

MAC infection presumably resulting from autoantibodies

to IFN-c. We should consider the presence of autoanti-

bodies to IFN-c when a patient with disseminated NTM

infection does not indicate the presence of HIV infection or

other immunosuppressive condition.

Acknowledgments We thank the members of Department of

Medicine (II) in Niigata University Medical and Dental Hospital for

their contribution to testing for the anti-IFN-c antibodies. We also

thank the members of Department of Orthopedics in Murayama

Medical Center for their contribution of surgical treatment.

Conflict of interest None.

References

1. Griffith DE, Akasamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C,

Gordin F, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treat-

ment, and prevention, of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am

J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367–416.

2. Prince DS, Peterson DD, Steiner RM, Gottlieb JE, Scott R, Israel HL,

et al. Infection with Mycobacterium avium complex in patients

without predisposing conditions. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:

863–8.

3. Horsburgh CR. Mycobacterium avium complex infection in

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1993;324:

1332–8.

4. Doffinger R, Dupuis S, Picard C, Fieschi C, Feinberg J, Barcenas-

Morales G, et al. Inherited disorders of IL-12- and IFN-c-

mediated immunity. Mol Immunol. 2002;38:903–9.

5. Kampitak T, Suwanpimolkul G, Browne S, Suankratay C.

Anti-interferon-c autoantibody and opportunistic infections: case

series and review of the literature. Infection. 2011;39:65–71.

6. Tanaka Y, Hori T, Ito K, Fujita T, Ishikawa T, Uchiyama T.

Disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection in a

patient with autoantibody to interferon-gamma. Intern Med.

2007;46:1005–9.

7. Koya T, Tsubata C, Kagamu H, Koyama K, Hayashi M, Kuwabara

K, et al. Anti-interferon-c autoantibody in a patient with disseminated

Mycobacterium avium complex. J Infect Chemother. 2009;15:

118–22.

8. Hoflich C, Sabat R, Rosseau S, Temmesfeld B, Slevogt H,

Docke WD, et al. Naturally occurring anti-IFN-gamma

1156 J Infect Chemother (2013) 19:1152–1157

123

autoantibody and severe infections with Mycobacterium chelo-

neae and Burkholderia cocovenenans. Blood. 2004;103:673–5.

9. Caruso A, Turano A. Natural antibodies to interferon-gamma.

Biotherapy. 1997;10:29–37.

10. Doffinger R, Helbert MR, Barcenas-Morales G, Yang K, Dupuis S,

Ceron-Gutierrez C, et al. Autoantibodies to interferon-c in a patient

with selective susceptibility to mycobacterial infection and organ

specific autoimmunity. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:e10–4.

11. Patel SY, Ding L, Brown MR, Lantz L, Gay T, Cohen S, et al.

Anti-IFN-c autoantibodies in disseminated nontuberculous

mycobacterial infections. J Immunol. 2005;175:4769–76.

12. Sarah KB, Rifat Z, Elizabeth PS, Kamonwan J, Lindsey BR, Li D,

et al. Anti-CD20 (rituximab) therapy for anti-IFN-c autoantibody-

associated nontuberculous mycobacterial infection. Blood. 2012;

119(17):3933–9.

J Infect Chemother (2013) 19:1152–1157 1157

123