Linus Magnusson - diva-portal.se › smash › get › diva2:974273 › FULLTEXT01.pdf ·...

Transcript of Linus Magnusson - diva-portal.se › smash › get › diva2:974273 › FULLTEXT01.pdf ·...

1

Examensarbete vid Institutionen för Geovetenskaper ISSN 1650-6553 Nr 99

Development and validation of a new mass-consistent model using terrain-

influenced coordinates

Linus Magnusson

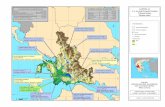

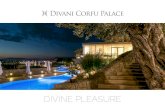

10 20 30 40 50 60

10

20

30

40

50

60

Time =18, Height =67.4, αz =4, Ri=−0.31905

km

Wind Speed λ − model m/s

5

5.5

6

6.5

7

7.5

8

8.5

9

10 20 30 40 50 60

10

20

30

40

50

60

km

Wind Speed MIUU model m/s

5

5.5

6

6.5

7

7.5

8

8.5

9

2

Abstract Simulations of the wind climate in complex terrain may be useful in many cases, e.g. for wind energy mapping. In this study a new mass-consistent model (MCM), the λ-model, was developed and the ability of the model was examined. In the model an initial wind field is adjusted to fulfill the requirement of being non-divergent at all points. The advance of the λ-model compared with previous MCM:s is the use of a terrain-influenced coordinate system. Except the wind field, the model parameters include constants α, one for each direction. Those constants have no obvious physical meaning and have to be determined empirically. To determine the ability and quality of the λ-model, the results were compared with results from the mesoscale MIUU-model. Firstly, comparisons were made for a Gauss-shaped hill, to find situations which are not caught by the λ-model, e.g. wakes and thermal effects. During daytime the results from the λ-model were good but the model fails during nighttime. From the comparisons between the models the importance of the α-constants were studied. Secondly, comparisons between the models were made for real terrain. Wind data from the MIUU-model with resolution 5 km was used as input data and was interpolated to a 1 km grid and made non-divergent by the λ-model. To study the quality of the results, they were compared with simulations from the MIUU-model with resolution 1 km. The results are quite accurate, after adjusting for a difference in mean wind speed between MIUU-model runs on 1km and 5 km resolution. Good results from the λ-model were reached if a climate average wind speed was calculated from several simulations with different wind directions. Especially if the mean wind speed for the domain in the λ-model was modified to the same level as in the MIUU 1 km. The λ-model may be a useful tool as the results were found to be reasonable good for many cases. But the user must be aware of situations when the model fails. Future studies could be done to investigate if the λ-model is useable for resolutions down to 100 meters.

3

Sammanfattning av ”Utveckling och utvärdering av en ny ’Mass-Consistent Model’ med terränginfluerat koordinatsystem” Modellering av vindklimat i komplex terräng är användbart i många sammanhang, t ex vid vindkartering för vindenergi. I den här studien utvecklas och undersöks användbarheten av en sk. Mass-Consistent Model, λ-modellen. Modellen bygger på att ett initialt vindfält justeras för att uppfylla kontinuitetsekvationen i alla punkter. För att göra vindfältet divergensfritt används en metod som bygger på variationskalkyl. Fördelen med denna nya modell jämfört med tidigare är användandet av ett terränginfluerat koordinatsystem. I teorin för λ-modellen införs en parameter α. Då denna inte har någon självklar fysikalisk betydelse behöver den bestämmas empiriskt. För att undersöka kvalitén hos λ-modellen gjordes jämförelser med den mesoskaliga MIUU-modellen. Det första steget var att jämföra körningar över en Gaussformad kulle, detta för att jämföra modellerna och finna situationer som λ-modellen inte löser upp. Exempel på sådana är termiska effekter och vakar. Resultaten under dagtid var bra medan under nattetid var det stora skillnader mellan modellerna. Utifrån resultaten kunde betydelsen av α-parametern studeras. Nästa steg var att jämföra med verklig terräng. Detta gjordes för ett område i Norrbotten. Här användes vinddata från MIUU-modellen med upplösning 5 km som indata för att beräkna vinden på en skala 1 km. För att undersöka kvalitén hos λ-modellen användes data från MIUU-modellen med upplösning 1 km som jämförelse. Resultaten avseende vindvariationerna i terrängen är tillfredställande, dock med något för höga vindhastigheter i λ-modellen. Detta visade sig bero på för högre medelvind i MIUU 5 km än i MIUU 1 km. Jämförelse mellan modellerna gjordes även för Suorva-dalen i Lappland vilken omges av bergig terräng. Resultaten här var sämre avseende medelvindarna, men med bättre resultat avseende vindriktningarna. Bra resultat för λ-modellen nåddes då resultat från flera simuleringar slogs samman till ett medelvärde. Framförallt blev resultatet bra då medelvinden justerades till samma nivå som MIUU 1 km. Sammanfattningsvis kan sägas att resultaten från λ-modellen är rimliga i många situationer men att det är viktigt att veta i vilka situationer den inte fungerar. Framtida undersökningar bör göras för att undersöka om modellen är användbar för upplösningar ner till ca 100 meter.

4

Contents 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 6 2. FLOW OVER HILLS .............................................................................................................................. 7 3. DESCRIPTION OF THE MIUU MODEL ............................................................................................ 9 4. THEORY..................................................................................................................................................10

4.1 CONSERVATION OF MASS.....................................................................................................................10 4.2 CALCULUS OF VARIATION....................................................................................................................11 4.3 TREATMENT OF THE CARTESIAN PROBLEM..........................................................................................11 4.4 TERRAIN-INFLUENCED COORDINATE SYSTEM ......................................................................................13 4.5 TREATMENT OF THE PROBLEM IN TERRAIN FOLLOWING COORDINATE SYSTEM....................................14 4.6 DISCRETISATION OF THE PROBLEM ......................................................................................................15 4.7 BOUNDARY CONDITIONS......................................................................................................................16 4.8 α-CONSTANTS......................................................................................................................................16

5. DESCRIPTION OF λ-MODEL .............................................................................................................17 5.1 COLLECTING DATA ..............................................................................................................................18 5.2 PREPARING DATA FOR λ-MODEL FROM MIUU 5 KM DATA...................................................................18 5.3 SOLVING THE EQUATION SYSTEM ........................................................................................................19

6. SIMULATED FLOW OVER HILL WITH λ-MODEL.......................................................................20 6.1 MODEL SETUP......................................................................................................................................20 6.2 RESULTS ..............................................................................................................................................21 6.3 DIVERGENCE .......................................................................................................................................22

7. SIMULATION – ARTIFICIAL HILL ..................................................................................................24 7.1 MODEL SETUP......................................................................................................................................24 7.2 RESULTS CASE 1..................................................................................................................................26 7.3 RESULTS FOR CASE 2...........................................................................................................................31 7.4 RESULTS AT OTHER LEVELS .................................................................................................................33

8. α-CONSTANTS.......................................................................................................................................33 8.1 PROPERTIES OF α-CONSTANTS .............................................................................................................33 8.2 CHOICE OF αZ.......................................................................................................................................35 8.3 IMPROVED USE OF α-CONSTANTS ........................................................................................................36

9. SIMULATION – AAPUA.......................................................................................................................37 9.1 MODEL SETUP......................................................................................................................................37 9.2 RESULTS ..............................................................................................................................................39

10. SIMULATION – SUORVA ..................................................................................................................44 10.1 MODEL SETUP ...................................................................................................................................44 10.2 RESULTS ............................................................................................................................................47

11. COMPOSITE SIMULATIONS ...........................................................................................................50 12. CONCLUSIONS....................................................................................................................................55

12.1 FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS ...................................................................................................................56 12.3 USING THE λ-MODEL WITH HIGHER RESOLUTION...............................................................................56

13. REFERENCES ......................................................................................................................................57 APPENDIX A. LIST OF SYMBOLS.........................................................................................................59

5

APPENDIX B. SOURCE CODE FOR THE NON-DIVERGENT PROCESS ......................................60 APPENDIX C. THE LINEAR EQUATION SYSTEM............................................................................64

6

1. Introduction The research on mesoscale models in complex terrain has been going on for many years and many different models have been developed. Due to the scale of interest, different simplifications of the basic equations of fluid mechanics have been done. For flow over hills both analytical and numerical models have been developed. Knowledge in the subject is important for example in air-pollution studies and wind energy mapping. There are various categories of numerical ‘flow over hill’ models. Firstly, they can be divided into two subgroups, steady state models and prognostic models (Pinard, 1999). Prognostic models take care of the basic equations of fluid mechanics (conservation of mass, momentum and energy) and are time dependent. An example of a prognostic mesoscale model is the MIUU-model, developed at the Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University. The model is hydrostatic, non-linear and uses higher order closure schemes. The MIUU-model is described in Section 3. In the steady-state models the assumption dU/dt=0 (acceleration term) is made (Pinard, 1999). Steady state models can be divided into two subgroups, mass conserving only and both mass and momentum conserving models. A theory for a two dimensional linear mass and momentum conservation model was introduced by Jackson and Hunt (1975). The theory divides the region above the hill into two parts. One inner region where the turbulence plays an important role on the mean flow and one outer region dominated by inertial forces. The equations for the perturbation were derived after linearization and other assumptions and solved with Fourier transforms. This report will focus on mass conservation models (MCM), also called mass-consistent models. MCM:s consist of two parts. Firstly, interpolating existing meteorological data into a three-dimensional grid generates the initial wind field. Secondly, the wind field is made non-divergent to fulfil the requirement of conservation of mass. For this, there exist different methods. One method, building on the Sasaki (1970) approach, uses calculus of variation to find the minimal value of an integral (see Section 4). In the late 70’s, two different models using this approach, MATHEW (Sherman, 1978) and MASCON (Dickerson, 1978), were developed. MASCON treats the sub-inversion layer as a single layer with variable height of the inversion. This theory gives an equation of constraint, which makes it possible to use calculus of variation to find the wind field. MATHEW treats a three dimensional problem instead of using the height of boundary layer. In Sherman (1978) MATHEW was used for assimilating a few observed data at ground to a domain. The initial upper wind is calculated from a power law and the geostrophic wind. The theory of MATHEW is described in Section 4.3.

7

In earlier papers, measurements were used as input data. These were interpolated into the domain grid. In Sherman (1978) the results of MATHEW was not verified with independent field data because all measurements were used as input data. In Walmsley et al (1990), a model called NOABLE*, building on the ideas from Sherman (1978), was compared with Mason-King Model D, MS-Micro/2 and BZ-WASP. These are three models building on the theory developed by Jackson and Hunt (1975). The comparisons also included measurements. The test area was Blashaval Hill, on the eastern side of the island of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. The models were in quite good agreement with each other and generally fell within the observed range of variation ±16% as compared to observation. Comparisons between the models showed that the three models building on Jackson and Hunt (1975) were somewhat better than NOABLE*. In Guo and Palutikof (1990) NOABLE* was compared with the MCM-model COMPLEX and measurements for three different sites in the UK. They compared the models with measurements also used as input data. Because adjustments were done by the models the results did not exactly match the measurements. They also found that NOABLE* overestimates wind speed at the top of the hill and underestimate the wind in low terrain. In this project the target was to find out whether it is possible to estimate the wind climate with a simple numerical model with high resolution. Therefore a new MCM-model, λ-model, was developed, building on the ideas from Sherman (1978). The major improvement with the new λ-model is the use of terrain-influenced coordinates and also the use of data from the MIUU-model as input data instead of measurements. The results from the new model are compared with results from the MIUU-model (simulations not used as input data) to determine the quality of the λ-model and to find cases when this model does not give a reliable result. To make it possible to find those situations, the theory of flow over hill was studied.

2. Flow over hills This short review from Stull (1988) chapter 14.2.3, explaining some general features regarding flow over hill is made in order to make it possible to explain the results from the λ-model and also the differences between the λ-model and the MIUU-model. The flow over a hill may differ quite a lot depending on stratification, wind speed and shape of the hill. Many “flow over hill” features are impossible to capture with the λ-model but may be found in the MIUU-model results, due to its more extensive physics. In a statically stable stratification, an air parcel lifted starts to oscillate with the Brunt-Väisälä frequency:

zgN

∂∂

=θ

θ0

2 (2.1)

8

When the parcel also moves with the flow, a wave-pattern is induced, so called lee waves. To describe the conditions in stable stratifications, the dimensionless Froude Number is introduced:

NHU

Fr = (2.2)

where H is the typical height scale of the hill or mountain.

Figure 2-1 a-e. The streamlines for the flow over hill for different Fr. After Stull (1988), p 602 For different Fr the streamlines over the hill will look quite different. For strongly stable stratification (Figure 2-1 a) with light wind, the buoyancy is dominating over dynamic forces. This leads to that the air is forced around the hill rather than over it. In front of the hill some air is blocked. For higher Fr (Figure 2-1 b) some of the air is passing over the hill. Behind the hill lee waves are formed by the perturbations caused by the hill. Some air is also streaming around the

9

hill. The wave formation is most intense for Fr=1 (Figure 2-1 c) when the natural wavelength of the air is the same as that of the hill. The theory behind lee waves is explained in Holton (1992). For Froude number above 1 (Figure 2-1 d) the dynamical effect dominates over buoyancy effect. This causes a cavity with reverse surface wind directions immediately behind the hill. For neutral stratification, which gives infinite Froude number, Fr is not a valid parameter. The wind field in front of the hill and above, is disturbed out to a distance of three times the size of the hill. Behind the hill there is a turbulent wake region with low mean wind speed. Above the top of the hill there is a speed-up effect, also called over-speeding. The shape of the wind profile above the hill is a combination between the speed-up effect and the friction at the ground. This combination gives a wind maximum at some height above ground. There are several analytical models describing the vertical profile; the maximum wind speed and the height for the maximum. The result from one analytical model (see Stull, 1988, pp 605) gives the magnitude of the speed-up for a three dimensional hill as percentage of the undisturbed wind speed,

½6.1 W

zM hillhill =∆ where ∆Mhill is the speed-up magnitude, zhill is

the height of the hill and W½ is the half width of the hill (distance between the top and the point where the elevation has decreased to half of its maximum). In Sections 7-11, the results from the λ-model and the MIUU-model will be compared and the differences found will be related to the different effects discussed in this section.

3. Description of the MIUU model The MIUU (short for Meteorological Institute, Uppsala University) model is a mesoscale model developed at the Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University during the latest 20 years (e.g. Enger 1990, Tjernström, 1987, Tjernström et al., 1988, Abiodun and Enger, 2002, Andrén, 1990, Mohr, 2003, Enger and Grisogono, 1998). The model is three dimensional, time dependent and hydrostatic. The coordinate system is the terrain following one described in Section 4.4 and the model uses a higher order closure scheme. Prognostic equations are used for horizontal wind, potential temperature, specific humidity and turbulent kinetic energy. For pressure, vertical velocity and other variables diagnostic equations are used for each time step. The vertical grid is staggered, with the wind components, temperature and humidity, on the main vertical levels and the turbulent energy defined in the vertical levels in between. The horizontal resolution can be specified equal at all grid points, telescopic with the highest resolution in the center of the domain or user-defined with uniform resolution in the center of the domain and sparser in the outermost grid points. Vertical levels are logarithmically spaced near the ground and linear for high levels. The numbers of vertical levels in the present simulations are 29 with the lowest on the height of z0 and the top at 10000 meters.

10

The model has for example been used to study terrain-induced flow, mountain waves, dispersion and wind-energy potential. For complex terrain, the MIUU-model has been used earlier with satisfactory results. In Bergström and Källstrand (2000), results from the MIUU-model are compared with measurements from 4 different sites in the Sourva valley. The result from the comparison shows that the MIUU-model nicely reproduces the wind field both in the valley and at the peak of one of the mountains near the valley. The MIUU model data will in this study be used as “true” values in comparison with the new λ-model. For the simulations with the MIUU-model the initial wind field was calculated from a pressure field corresponding to a specified geostrophic wind speed and direction. When the model starts running the radiation balance satisfies the midnight conditions. The results from the model are stored as the average fields once every hour. Results from the first hours of the model simulations are not in equilibrium, but hour 12 is close to equilibrium and thus used for comparisons in this report.

4. Theory Wind field simulations with a prognostic mesoscale model such as the MIUU-model needs much computer time. A more economic way is to use a simpler model. In this section the theory behind a mass-consistent model (MCM) will be discussed and modified to use a terrain-influenced coordinate system. The problem to solve in a MCM-model is to adjust a wind field so that it satisfies the conservation of mass in every grid point and the adjustment of the original field will be minimized. The reason for minimizing the adjustment is that the most reasonable solution which is non-divergent is the solution closest to the input data. To make it easy to implement the terrain it is preferable to use a terrain-influenced coordinate system. The derivation of the solution to the problem is based on calculus of variation which is a mathematical technique to find a minimal (or maximal) solution for an integral. This theory applied to a Cartesian system is earlier described in Sherman (1978).

4.1 Conservation of mass One of the basic equations in fluid dynamics is conservation of mass in the system.

( )[ ]Ut

rρρ

⋅∇−=∂∂ (4.1)

Under condition that the circulation is much less than scale depth of the atmosphere it is possible to use the shallow convection continuity equation (Pielke, 1984):

0=⋅∇ Ur

(4.1’) This is working under the assumption of incompressibility and homogeneity (constant density). This assumption is used in many mesoscale models.

11

4.2 Calculus of variation Calculus of variation is one of the main techniques in mathematics and physics. For a derivation of the theory, see Simmons (1999) chapter 12. The idea is to find the function y(x) so that the integral I has a minimum solution.

( ) ( ){ }∫=2

1

;',x

x

dxxxyxyfI (4.2)

where ( )dxdyxy ='

f is a known function and the limits are fixed. The minimal solution of the integral I can be found by Euler’s equation:

0'=

∂∂

−∂∂

yf

dxd

yf (4.3)

The theory is powerful and applicable in various problems. For example, calculus of variation is the basic idea for Hamiltonian and Lagrangian mechanics. The theory works in the same manner for more than one unknown function:

0'=

∂∂

−∂∂

ii yf

dxd

yf (4.3’)

If yi is working under the condition g(x,y)=0 (e.g the motion is limited to a plane or conservation of mass), a new function can be introduced, gfF λ+= , where λ is Lagrange multiplier. λ is a variable that describes the adjustment that has to be done to satisfy the condition. The minimum of the integral is then found from:

0'=

∂∂

−∂∂

ii yF

dxd

yF (4.3’’)

It gives us i equations plus the constrain equation which together close the system of equations.

4.3 Treatment of the Cartesian problem In order to make the wind field mass-consistent in a Cartesian coordinate system, the key is to minimize the integral in Eq. (4.4). The reason why the integral shall be minimized is that the resulting wind field solution should be the solution closest to the input wind field. Because the resulting wind field is non-divergent, that part of the integral is zero, see Eq. (6d).

12

( ) ( ) ( )∫∫∫ ⎥⎦

⎤⎢⎣

⎡∂∂

+∂∂

+∂∂

+−+−+−= dxdydzzw

yv

xuwwvvuuI zyx λααα 2~~~ 222222 (4.4)

(Difference between the fields) + 2λ (Continuity equation) αx,y,z are constants named Gaussian Precision Moduli and are described in Section 4.8. Splitting the integral in components gives:

( ) ( ) '2~;', 22 uuuxuuF xu λα +−= (4.5a)

( ) ( ) '2~;', 22 vvvyvvF yv λα +−= (4.5b)

( ) ( ) '2~,', 22 wwwzwwF zw λα +−= (4.5c) This step is not described in any of the reference papers. But to reach the result below with the Euler equation this step is needed. The theory of variational calculus says that the wind field giving the minimal solution for the integral in Eq. (4.4) can be found using Euler equation (Eq. 4.3’’). That gives rise to the following three equations for the adjusted wind field.

dxduu

x

λα 2

1~ += (4.6a)

dydvv

y

λα 2

1~ += (4.6b)

dzdww

z

λα 2

1~ += (4.6c)

The adjusted components must satisfy the continuity equation which is the constrain equation. Eq. (4.6 a-c) differentiated and inserted into the continuity equation gives:

2

2

22

2

22

2

2

1~1~1~0

zzw

yyv

xxu

zw

yv

xu

zyx ∂∂

+∂∂

+∂∂

+∂∂

+∂∂

+∂∂

==∂∂

+∂∂

+∂∂ λ

αλ

αλ

α

which can be rewritten to:

⎥⎦

⎤⎢⎣

⎡∂∂

+∂∂

+∂∂

−=∂∂

+∂∂

+∂∂

zw

yv

xu

zyx zyx

~~~1112

2

22

2

22

2

2

λα

λα

λα

(4.6d)

To find the adjusted wind field the problem to solve is actually the equation system (4.6a-d). In Eq. (4.6d) λ is the only unknown variable and therefore Eq. (4.6d) can be solved independently. But the equation is a differential equation on a form called Poissons equation. This differential equation is difficult to solve (in many cases impossible) analytically and therefore has to be solved numerically. When Eq. (4.6d) is solved the adjusted wind field can easily be found from equations (4.6a-c).

13

4.4 Terrain-influenced coordinate system The terrain-influenced coordinate system described below uses the conventional horizontal Cartesian coordinates but a terrain-influenced vertical coordinate η, which is by definition:

( ) ( )[ ]( )[ ]yxzs

yxzzszyx

G

G

,,

,,−−

=η (4.7)

where s is the top height of the model and zG is the height of ground. This system is terrain following near ground and plane at the top; η = 0 at z = zG and η = s at z = s. The base vectors are non-orthogonal. (Pielke, 1984)

Figure 4-1. Shows the vertical levels above a hill. After Pielke (1984) The system has following properties: u* = u v* = v

[ ]GG

G

G

G

zssw

zss

yz

vzss

xz

uw−

+⎟⎟⎠

⎞⎜⎜⎝

⎛−−

∂∂

+⎟⎟⎠

⎞⎜⎜⎝

⎛−−

∂∂

=ηη* (4.8)

In the following text the symbols u, v and w* are used as symbols for the terrain following components. The continuity equation:

( )[ ] 01 ** =−

∂∂

− iGiG

uzsxzs

ρ (4.9)

Under assumption of incompressible gas and horizontal homogeneity in density the continuity equation becomes:

011*

=∂∂

−−

∂∂

−−

∂∂

+∂∂

+∂∂ v

yz

zsu

xz

zsw

yv

xu G

G

G

Gη (4.9’)

14

4.5 Treatment of the problem in terrain following coordinate system One problem when using the Cartesian coordinate system is to incorporate a complex terrain into a model. Therefore, it is easier to use a terrain following coordinate system. For the coordinate system described in Section 4.4, the corresponding integral to Eq. (4.4) is:

( ) ( ) ( )

∫∫∫⎥⎥⎥⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢⎢⎢⎢

⎣

⎡

⎥⎥⎦

⎤

⎢⎢⎣

⎡⎥⎦

⎤⎢⎣

⎡∂

∂+

∂

∂

−−

∂∂

+∂∂

+∂∂

+

−+−+−

= η

ηλ

ααα

dxdyd

yz

vxz

uzs

wyv

xu

wwvvuuI

gg

g

zyx

12

~~~

*

2**22222

(4.10)

The steps to find the adjusted wind field are the same as in Section 4.3. The integral function divided into components:

( ) [ ]uZuuuF xxu −+−= '2~ 22 λα (4.11a)

( ) [ ]vZvvvF yyv −+−= '2~ 22 λα (4.11b)

( ) '2~ *2**2 wwwF zw λα +−= (4.11c) there, for simplicity:

xz

zsZ g

gx ∂

∂

−=

1 (4.12a)

yz

zsZ g

gy ∂

∂

−=

1 (4.12b)

Using Euler equation (Eq. 4.3’’) on the equations (4.11a-c) gives:

λα

λα x

xx

Zdxduu 22

11~ ++= (4.14a)

λα

λα y

yy

Zdydvv 22

11~ ++= (4.14b)

ηλ

α ddww

z2

** 1~ += (4.14c)

These equations differentiated and inserted in the continuity equation (Eq. 4.9’) and after some re-arranging gives:

15

[ ] [ ]

⎥⎦

⎤⎢⎣

⎡−−

∂∂

+∂∂

+∂∂

−=⎟⎟⎠

⎞⎜⎜⎝

⎛+

∂∂

−⎟⎠⎞

⎜⎝⎛ +∂∂

−∂∂

+∂∂

+∂∂

+∂∂

+∂∂

vZuZwyv

xuZ

yZZ

xZ

Zy

Zxyx

yxyy

yxx

x

yy

xxzyx

~~~~~11

11111

*

22

222

2

22

2

22

2

2

ηλλ

αλλ

α

λα

λαη

λα

λα

λα

(4.14d)

(4.14a-d) is an equation system of u,v,w* and λ. The system can be solved by first solving the differential equation (Eq. 4.14d), because that equation is only dependent on λ. Eq. (4.14d) can be simplified by using the chain rule for differentials. The reason why not doing so is that it gives a small numerical error.

4.6 Discretisation of the problem Eq. (4.14d) is on the form 3221

23 kkk =−∇−∇ λλλ where ∇3

2 is the three dimensional

second order differential operator and ∇2 is the horizontal first order differential operator. k1,2,3 are constants. When using finite differences on Eq. (4.14d) the numerical problem is set on the form of Aλ = b, which is a basic linear algebra problem. The three-dimensional matrix of λ can be rewritten as a vector by putting every element in the matrix in the vector (see Appendix B, fcnHLvektor). That gives the dimension of A as two. The size of A will be the square of the length of λ (number of elements). The matrix is very sparse with only 7 non-zero elements in each row (see below). An example of the equation system is shown in Appendix C. From Kapotza and Eppel (1986) the first and second derivatives for an arbitrary function p can be expressed through:

( )( )11

12

12

12

112

++

−+++

+−−−

=∂∂

iiii

iiiiii

hhhhphphhph

xp (4.15a)

( )[ ]( )11

11112

2 2

++

−+++

+++−

=∂∂

iiii

iiiiiii

hhhhphphhph

xp (4.15b)

hi is the distance between pi-1 and pi. Using these discretisations of the derivatives does not make it necessary to have an equal spaced grid. Using the finite differences on the left hand side of (4.14d) gives the following equation system (4.16):

( )( )

( )( ) ( ) 1,,

1122

,1,11

1,,2,,1

11

,1,2

212121+

+++

++

++

++

+

++

⎥⎥⎦

⎤

⎢⎢⎣

⎡

+

−−+⎥

⎦

⎤⎢⎣

⎡+

−−kji

kkkkji

jjj

jjiji

xkji

iii

ijiji

x hhhhhhhZxZx

hhhhZxZx

λα

λα

λα Bx By Bz

16

kjijiy

jixkkzjjyiix

ZyZxhhhhhh ,,

2,2

2,2

12

12

12

11212121 λααααα ⎥

⎥⎦

⎤

⎢⎢⎣

⎡−−−−−+

+++

(4.16)

O

( )( )

( )( ) ( ) 1,,

12,1,

1

1,1,2,,1

1

1,1,2

212121−

+−

+

+−−

+

+−

++

⎥⎥⎦

⎤

⎢⎢⎣

⎡

+

−−+⎥

⎦

⎤⎢⎣

⎡+

−−+ kji

kkkzkji

jjj

jjiji

xkji

iii

ijiji

x hhhhhhhZxZx

hhhhZxZx

λα

λα

λα

Ax Ay Az The non-zero elements in A are aligned at these positions (see Appendix C): (Y number of elements in j, Z number of elements in k) O n,n Ax n,n-YZ Ay n,n-Z Az n,n-1 Bx n,n+YZ By n,n+Y Bz n,n+1 The discretisation of the right hand side of (4.14d) gives:

( )( )

( )( )

( )( )

⎥⎥⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢⎢⎢

⎣

⎡

−−

−+

−−−+

+

−−−+

+−−−

− ++

−+++

++

−+++

++

−+++

jjiiji

kkkk

kkkkkkk

jjjj

jjijjjj

iiii

iiiiii

vZyuZxhhhh

whwhhwhhhhh

vhvhhvhhhhh

uhuhhuh

~~

~~~~~~~~~

,,

11

12

12

12

12

11

12

12

12

12

11

12

12

12

112

(4.17)

4.7 Boundary conditions From Sherman (1978) the boundary must satisfy ( ) 0=xnxλδ . This means that λ has to be zero on the boundary, or that the adjustment in normal direction to the boundary has to be zero (dλ/dn=0). Those two boundary conditions have different physical meanings. λ=0 is called open boundary and allows adjustment in normal direction on the boundary but not in non-normal direction. The other condition is called closed boundary. Closed boundary in combination with zero wind on the boundary gives no flow through the boundary. Closed boundaries are used for the bottom of the model and open for the other ones. How the boundary conditions appear in the equation system is shown in Appendix C.

4.8 α-constants In Sherman (1978) the definition for Gaussian precision moduli is αi

2=1/2σi2, where σ is the

deviation in the wind field. The deviation can be expressed as observational deviation, spatial deviation or deviation from the desired field. In Gao and Palutikof (1990) the α-constant is connected with the stratification. The connection is possible to do because a large αz does not allow adjustment in the vertical wind (and in the same manner for the horizontal wind). Dominant adjustment in the horizontal wind is related to stable stratification and adjustment

17

in vertical wind is related to unstable conditions. αx=αy=αz shall represent the neutral condition when the adjustment is evenly distributed. This is a large simplification because there are other phenomena due to stratification that is not possible to resolve in this kind of model, e.g. wakes, blocking and lee waves. In the derivation of Eq. (14a-d), α is treated as a constant. It implies that the divergence will not be zero if α is allowed to vary in the domain. The results of different α-values will be discussed in Section 8.

5. Description of λ-model The λ-model code is created in Matlab (The Mathworks, Inc). The advantages of using Matlab are the handling of matrices and all plotting functions. The matrix A (see Section 4.6) has to be defined as a sparse matrix due to the memory capacity. Other built in functions used in the model are functions for interpolation and the \-operator (Pärt-Enander and Sjöberg, 2001) for solving equation systems. The model can be divided into three parts; collecting data from the MIUU-model, preparation of data for the λ-model from MIUU 5 km (5 km horizontal resolution) and finally solving the equation system. The description of collecting data and preparation of data, will mainly describe the case then the λ-model is running with MIUU 5 km data as input field, and with MIUU 1 km (1 km horizontal resolution) terrain map. Figure 5-1 shows the structure for the two processes.

18

Collecting data from MIUU-model

Input parameters:•Input domain corners•Number of vertical levels for input data•Dataset•Time

Get terrain from files

Get horisonal grid from files

Get vertical levels from files

Find out the grid points corresponding to the domain corners

Get the wind field from MIUU-model res-files

Cut out the grid and terrain for the input domain

Preparing data for λ-model from MIUU 5km

dataInput parameters:•α-constants•Number of vertical levels in λ-model•Collected data from MIUU-model

Set number of gridpoints in each direction

Creates grid for the λ-model domain

Cut out terrain for λ-model from MIUU 1 km terrrain map

Get vertical levels (same as MIUU 5 km)

Set maximum model height

Set α constants

Change the columns and rows in all matrices

Create matrices Zx and Zy

Interpolate MIUU 5 km data to λ-model grid

Transform the Cartesian vertical velocity to terrain following coordinates system

Figure 5-1. The steps for collecting and preparing data for the λ-model.

5.1 Collecting data Before running the λ-model, data from the MIUU-model has to be collected. The wind data is saved in files for every hour of simulation. The grid data, vertical levels and zg values are saved in separate files. Before collecting all this data some parameters have to be set. Those are corners of the input data domain, number of vertical levels that will be used, name of dataset and for which hour the data should be read. The values for the corners have to be set in Swedish National Coordinates. The corners are used to calculate the location of new domain from the MIUU-model data. Then new variables are created for the grid and the terrain (zg-values) of the new domain and the wind field is loaded from MIUU-model result files. The wind components are saved in a three dimensional matrix, one for each component. Data is collected both for 1 km and 5 km runs with the MIUU-model.

5.2 Preparing data for λ-model from MIUU 5 km data Before starting the simulations with the λ-model, which will make the wind field non-divergent, a first guess of the wind components has to be done.

19

The input parameters for the preparation process are the α-constants and the data collected from the MIUU-model. The number of grid points and the domain for the λ-model is determined from the size of the input data domain. The domain for the λ-model has to be smaller than the input data domain because the wind data can only be interpolated to a smaller domain with reliable result. The terrain map from MIUU 1 km is used for the λ-model. The vertical levels for the λ-model are set to the same vertical levels as in the MIUU 5 km model. The top of the λ-model is determined from numbers of vertical grid points. The first guess for the wind field is created by using the built in Matlab function interp3 which interpolates the 5 km spaced data to the new 1 km spaced grid. The type of interpolation used here is linear interpolation. Spline interpolation has been tested but can sometimes give strange results, especially near borders. The vertical wind component is not interpolated. Instead the Cartesian vertical velocity is set to zero and the terrain following vertical wind velocity is calculated from Eq. (4.8). This treatment of the vertical wind will be discussed in Section 6.1.

5.3 Solving the equation system To make the wind field non-divergent the equation system (14a-d) has to be solved. In Appendix B the source code for the subroutine fcnKorM2 and the underlying functions are shown. Firstly, the right-hand side of Eq. (4.14d) is created (fcnB) by calculating the divergence of the input wind field from Eq. (4.17) (see subroutine fcnUkont). The divergence is set to zero for all boundary points. The reason for this is to form the boundary conditions (see below). To make it possible to use the built in equation system \-operator in Matlab, the right-hand side has to be a vector. Therefore the elements in the divergence matrix have been put into a vector. This is made in the subroutine fcnHLvektor. The matrix A is created in subroutine fcnMat2. The matrix is two dimensional and its size equals the number of grid points squared. For a domain size of 61x61x23 the size of the matrix is 85583 x 85583. To make it possible to store the matrix in the computer memory, the matrix is declared as a sparse matrix in Matlab, implying that computer memory is only allocated for the non-zero elements. For all boundary points except the lower boundary the value on the diagonal is set to 1. This in combination with zero-values in the right-hand side of Eq. (4.14d) gives the boundary condition λ=0. At the lower boundary the diagonal numbers are also set to 1 but here the value to the right of the diagonal is set to -1. With the right-hand side of Eq. (4.14d) equal to zero, this gives the boundary condition λ1-λ2=0. For all other rows the elements are given according to Eq. (4.16). An example of the matrix A is shown in Appendix C. The differential equation (Eq. 4.14d) is then solved with the \-operator which implies that the equation system is usually solved by Gaussian elimination with LU (LowerUpper)-factorization (for details see any literature in scientific computing). The result from the solved equation system is a vector containing a λ-value for all grid points in the domain. To transform the elements of the vector with λ-values in to a matrix, the function FknLmat is used. This function does the reversed procedure from the function fcnHLvektor.

20

When the values of λ are determined at all grid points the new wind field can be calculated from equations (4.14a-c) (see fcnUny, fcnVny and fcnWny). To get the Cartesian vertical velocity Eq. (4.8) is used (fcnWT2W).

6. Simulated flow over hill with λ-model

6.1 Model setup To study the resulting wind field from the λ-model, simulations were performed for an artificial hill. The equation for the terrain was given by:

( ) ( )( )( )22max exp ccg YjXiszz −+−−= (6.1)

This equation gives a 2-D Gaussian distribution. zmax is the maximum height of the hill. S is a parameter for the steepness of the hill. Point (Xc,Yc) is the central point of the hill. Here the maximum height was set to 300 meter and the steepness parameter to 0.08. This gives a maximum terrain gradient of 6.7 cm/m. The shape of the hill is shown in Figure 6-1.

0.51

1.52

2.53

x 104

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

x 104

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

m

Terrain

m Figure 6-1. The shape of the Gaussian hill with the maximum height 300 meters. The input wind field was set to u = w = 0 and v=10 m/s for heights above 50 m. For heights below 50 meters the logarithmic wind law was used with z0=0.01. The use of w = 0 does not imply that w* necessarily will be equal to zero, see Eq. (4.8). The choice of w=0 instead of w*=0 will result in a larger divergence. Using w* = 0 means that

21

the air flow follows the terrain and divergence will only be created by the compression of the terrain following coordinate system. Using w = 0 leads to that the air is initially blowing into the hill, which will give a larger divergence. If w*=0 is used the adjustment will be too small in the horizontal direction. This treatment of the vertical wind is one of the key points to get a physically relevant result from the λ-model. The α-constants was set to αx=αy=1 and αz=4. This choice gives more adjustment in the horizontal directions than in the vertical, see Section 8. The grid size was 31x31x20 with a horizontal spacing of 1000 meters. In vertical, the spacing varies with height. The levels are 0, 2, 4, 10, 20, 50, 100, 150, 200, 300, 400 and above 400 m every 200 meter up to 2200 meters.

6.2 Results All results from the λ-model are plotted in a terrain following level. This means that the altitude is not the height above sea level. The terrain following level is comparable to height over terrain but is not exactly the same (see Figure 4-1).

1 2 3

x 104

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3x 10

4

x (m)

y (m

)

(a) u component m/s

−0.6

−0.4

−0.2

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

1 2 3

x 104

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3x 10

4

x (m)

y (m

)(b) v component m/s

9.5

10

10.5

11

11.5

1 2 3

x 104

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3x 10

4

x (m)

y (m

)

(c) w component m/s

−0.4

−0.2

0

0.2

0.4

1 2 3

x 104

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3x 10

4

x (m)

y (m

)

(d) Wind Speed m/s

9.5

10

10.5

11

11.5

Figure 6-2a-d . The adjusted u- (a), v- (b), w-(c) component and wind speed(d) at Height=50 m. Figure 6-2a shows the adjusted u-component at 50 meters height. It shows that the flow is going around the hill. The adjustment on this level is as a maximum 7 % of the wind speed in

22

the original field but it is dependent on the choice of αz and the shape of the hill. The symmetry is a result of the homogeneous input wind field. The physics in the model is symmetric in the way that symmetric divergence implies symmetric adjustment. Figure 6-2b shows the v component at 50 meters height. Just above the hill there is a speed-up of the flow. In front of and behind the hill the wind speed is decreased. The speed-up effect is also dependent of the choice of αz. The fact that the maximum is located exactly above the hill is not true in reality. Instead the maximum is usually located behind the hill (see simulation results from MIUU-model in Section 7). This difference is one of the error sources in the model. The minimum in front of and behind the hill is of the same magnitude, which is also a problem. In very stable stratification, air is blocked in front of the hill, which gives a stronger minimum there. During unstable or weakly stable stratification, a wake behind the hill gives a larger area with low speed than in front of the hill for this case. Figure 6-2c shows the Cartesian vertical velocity at 50 meters height. It shows that in front of the hill the air is ascending and descending behind the hill. The wind speed showed in Fig 6-2d is calculated in the following way:

22 vuU += (6.2) The picture looks nearly the same as the v-component. The reason for this is the fact that the v-component is much larger than the u-component. The wind speed is the parameter that will be most extensively used in the comparisons between the λ-model and the MIUU-model.

6.3 Divergence The distribution of the divergence in the input field is plotted in Figure 6-3 and shows the symmetry discussed above.

23

0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3

x 104

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

x 104

x (m)

y (m

)

Divergence in the input field s−1

−2.5

−2

−1.5

−1

−0.5

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

x 10−4

Figure 6-3. The divergence in the input field for level 6 (50 m). Due to the theoretical treatment of the flow, (Eq. 4.14d), the divergence has to be very close to zero. But if the resulting wind field is inserted in the continuity equation, the error will be much larger as seen in Table 6-1, column 2. This is caused by the treatment of the discretisations of differentials. Using the first order differential operator (Eq. 4.15a) two times will not give the same result as using the second order (Eq. 4.15b) one time. The discretisation of the differential equation (Eq. 4.16) uses the second order operator. Afterwards the first order operator is used to find the adjusted field. The fact that the continuity equation also uses the first order is the reason for this error. The divergence in the input field is confined to the lowest 6 levels. The reason for this is that there is a wind shear following the logarithmic wind law for these levels. Table 6-1 shows the maximum divergence for each level except the bottom and the top. The values for the resulting field are calculated by putting the adjusted wind field into the continuity equation, which gives the problem discussed above. The results in the right-hand column are calculated by putting the calculated λ-values into Eq. (4.14d).

24

Table 6-1. The divergence for level 2 to 19. The reason for the difference between column 2 and 3 is discussed above.

Level Height

(m) Input field Resulting field Divergence from eqn 14d

2 2 0.12 0.052 2.78e-014 3 4 0.023 0.033 1.06e-014 4 10 0.0094 0.0033 1.73e-015 5 20 0.0046 0.0013 3.67e-016 6 50 0.0015 0.00061 8.02e-017 7 100 9.49e-019 0.00028 4.92e-017 8 150 1.33e-018 0.00010 3.45e-017 9 200 1.57e-018 8.84e-005 1.77e-017 10 300 3.79e-019 6.85e-005 9.02e-018 11 400 3.79e-019 5.75e-005 4.47e-018 12 600 3.25e-019 3.99e-005 2.48e-018 13 800 1.63e-019 2.11e-005 1.56e-018 14 1000 1.63e-019 1.23e-005 1.53e-018 15 1200 1.084e-019 7.32e-006 1.10e-018 16 1400 1.084e-019 4.38e-006 7.31e-019 17 1600 5.42e-020 2.59e-006 4.58e-019 18 1800 5.42e-020 1.45e-006 2.91e-019 19 2000 5.42e-020 6.62e-007 1.91e-019

7. Simulation – Artificial hill To determine the quality and ability of the λ-model, a large number of different simulations have been made. The results of the simulations were then compared with results from the MIUU-model. The model comparisons were also used to find the optimal values of αz for different meteorological conditions.

7.1 Model setup To make the comparison simple, the terrain was created as a 2-dimensional Gaussian distribution (Eq. 6.1). See Figure 6-1 for an example of a hill created with this equation. Three different shapes of the hill are used in this test. Hill 2 and 3 have the same area but the heights are 600 and 100 meters respectively. Hill 1 covers a larger area and the height is 300 meters. Table 7-1. Parameters for the different hills used in the simulations. Maximum height Steepness parameter Maximum gradient Hill 1 300 0.02 3.6 cm/m Hill 2 600 0.08 13.4 cm/m Hill 3 100 0.08 2.2 cm/m

25

To examine the importance of the α-constants, different αz-values were used in the simulations, while αx and αy were set to 1 for all simulations (see Section 8.1). Simulations with the MIUU-model were made for the same terrain as the λ-model and resolution was set to 1 km. As initial conditions the geostrophic wind was set to 9 m/s and the radiation condition was comparable to that in April in southern Sweden. The results were given as 36 different hourly averages. This makes it possible to do an analyzsis covering both day and night conditions. Comparisons between the models were made for every second hour between 12 and 36. The input wind field to the λ-model was implemented in two different ways. In Case 1, the vertical wind profile from point (10, 10) in the MIUU-model (cf. Fig 7.2) was chosen. The point is located upstream the hill and chosen so that it is not affected by the hill. This wind profile was used as an input wind field profile in every grid point in the λ-model. The vertical wind w was set to zero, when the terrain-influenced w* was calculated. This choice of input wind field can be related to the case where the wind field does not “know” the presence of the hill; i.e. is not affected by the hill. It is comparable to the use of model data calculated with a lower resolution terrain map. Values for αz used in this case were 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. In Case 2, vertical wind profiles from every tenth point of the MIUU-data were used as input. This data was interpolated to all grid points by linear interpolation. Spline interpolation was tested but with bad results, especially near borders. Due to the interpolation, the model domain in this case was restricted to 41x41. This input field “knows” the presence of the hill, because the MIUU-model uses the same terrain map as the λ-model. This case can be compared with using measurements as input data. Values for αz used in this case were 1, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 5. The λ-model was run in Case 1 with a grid size of 61x61x20 and in Case 2 with 41x41x20. In both cases the resolution was 1 km, the same as in the MIUU-model. The time needed for one simulation for Case 1 is around 90 seconds on an Intel Pentium 4 3.00 GHz with 1024 Mb RAM. If nothing else is said, the results aregiven for 67.4 meters height, which is level 8 in both models. The results from the λ-model are compared with the results from the MIUU – model. The main parameter compared is the horizontal wind speed; the absolute value of u- and v-components. For comparisons, the difference in wind speed between the models is calculated in every point and normalized with the mean speed of the MIUU – model for the present level. It gives the new parameter D, defined as:

26

meanMIUU

MIUU

UUU

D−

= λλ (7.1)

In the same way the normalized difference for the input wind field compared with the MIUU-model result is calculated which gives the parameter inD . To get a value of the overall quality for a certain level, the mean of the absolute value of D is calculated for a level as:

( )

IJ

jiDD

I

i

J

j∑∑= == 0 0

2,λ

λ (7.2)

7.2 Results for Case 1 In Table 7-2, different quality parameters are shown for Hill 2 and Case 1. In column 2, the values of λD is shown for different hours. The value gives a measure of the overall agreement between the λ-model and the MIUU-model. The ratio shown in column 3 gives a value for the improvement of the wind field with the λ-model simulation. In column 4 and 5 the maximum and minimum value of λD for the level are shown. This gives the span for the distribution of the differences between the λ-model and the MIUU-model. A distribution for

λD is plotted in Figure 7-4. In column 6 the Richardsons number (Ri) is shown for level 8 (67 m) and at point (10,10). The definition of Ri is:

2

⎟⎠⎞

⎜⎝⎛∂∂

∂∂

=

zU

zg

Ri

θθ (7.3)

The gradients in Ri are approximated by the differences between the present level and the level above. All values for λD shown for each hour are calculated for the simulation with the optimal choice of αz as found according to the minimum of λD . This value for αz is shown in column 7. Another important parameter to study is the speed up-effect on the top of the hill. Optimal αz to get a maximum value of the wind speed is shown in the last column.

27

Table 7-2. Different quality parameters for Hill 2, Case 1 and level 8 (67 m). Hour

λD Ratio

inDDλ

Max λD Min λD Ri Optimal αz

for λD Optimal αz

for maximum wind speed

12 0.055 0.91 0.46 -0.54 -1.54 5 5 14 0.034 0.89 0.35 -0.36 -1.20 4 4 16 0.021 0.81 0.33 -0.31 -0.96 4 3 18 0.015 0.79 0.33 -0.31 -0.32 4 3 20 0.025 0.82 0.43 -0.50 0.18 5 4 22 0.036 0.94 0.34 -0.58 0.36 4 4 24 0.063 0.98 0.55 -0.57 0.39 3 4 26 0.109 0.99 0.80 -0.39 0.39 2 3 28 0.173 1.00 1.03 -0.07 0.40 3 1 30 0.170 1.00 1.03 -0.16 0.42 3 1 32 0.192 0.93 0.67 -1.28 0.04 7 7 34 0.144 0.94 0.40 -1.47 -4.57 7 7 36 0.052 0.94 0.40 -0.28 -0.61 3 3

Table 7-2 shows that the λ-model works quite well during afternoons and evenings but fails during nighttime and in the mornings. Between hour 24 and 30 the improvement ratio is nearly 1 which means that the λ-model does not improve the wind field compared to the interpolated data. As the λ-model does not handle thermal effects, the calculated wind from the model is nearly the same day and night. The only differences come from the input wind field. The MIUU-model handles stratification effects and gives different results for night and day. This is shown for Case 1 in Figure 7-2 and 7-3. The terrain used for these results are Hill 2. The simulation in Figure 7-2 is for daytime (hour 16) with unstable stratification. The simulations from the two models look the same in front of and above the hill. Behind the hill a wake is appearing in the MIUU-model. This is a non-linear effect not resolved by the simple physics used in the λ-model. Another difference, hard to see in Figure 7-2, is that the maximum wind speed in the MIUU-model simulations is located somewhat behind the top of the hill instead of right above the top as in the λ-model.

28

10 20 30 40 50 60

10

20

30

40

50

60

Time =16, Height =67.4, αz =4, Ri=−0.95886

(b) Wind Speed λ − model m/s

4

4.5

5

5.5

6

6.5

7

7.5

8

10 20 30 40 50 60

10

20

30

40

50

60

(a) Wind Speed MIUU model m/s

4

4.5

5

5.5

6

6.5

7

7.5

8

Figure 7-2. Simulations by MIUU-model (a) and λ-model (b) for daytime. Hill 2 and Case 1.

29

10 20 30 40 50 60

10

20

30

40

50

60

Time =28, Height =67.4, αz =3, Ri=0.40077

(b) Wind Speed λ − model m/s

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

10 20 30 40 50 60

10

20

30

40

50

60

(a) Wind Speed MIUU model m/s

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Figure 7-3. Simulations by MIUU-model (a) and λ-model (b) for nighttime. Notice that the wind speed goes down to nearly zero in the MIUU-model simulation. Hill 2 and Case 1.

30

In Figure 7-3 (showing the wind speed for nighttime conditions), the results from the two models differ significantly. The thermal effects are dominating in the MIUU-model simulations. Firstly, air is blocked in front of the hill which is caused by stable stratification (see Figure 2-1a). Beside the hill, air flows out from the hill as an effect of cooling of air close to the surface of the hill. This cooler air is denser than the surrounding air and the flow will be downslope on both sides of the hill. Those two effects have nothing to do with conservation of mass when air is flowing over the hill and they are therefore not caught by the λ-model. The improvement of the wind field by running the λ-model can be illustrated by comparing the distribution of λD in the input field and the λ-model field.

−0.2 −0.15 −0.1 −0.05 0 0.05 0.1 0.15 0.20

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Distribution of Dλ

Dλ

Rel

ativ

e F

requ

ency

%

λ − modelInput field

Figure 7-4. The distribution of λD in the input field and the λ-model field. The simulations is for Hill 1, hour 18 and αz=5. Figure 7-4 shows that the points with large λD have disappeared after running the λ-model, especially on the negative side. This is caused by the creation of the speed-up maximum above the top of the hill. The improvement on the positive side is caused by the areas with low speed both in front of and behind the hill created by the λ-model. When comparing all hours, the conclusion is that the most accurate results from the λ-model appears between hour 12 and hour 20. All others hours have strong thermal effects which are not captured by the λ-model.

31

7.3 Results for Case 2 Table 7-3. Different quality parameters for Case 2 and level 8 (67 m).

Hour λD Ratio

inDDλ

Max λD Min λD Ri Optimal αz

for λD Optimal αz

for maximum

wind speed 12 0.022 0.83 0.47 -0.67 -1.54 4 5 14 0.018 0.81 0.19 -0.47 -1.20 3.5 4 16 0.013 0.75 0.16 -0.43 -0.96 3 3 18 0.010 0.70 0.12 -0.40 -0.32 3 3 20 0.016 0.75 0.30 -0.59 0.18 3.5 4 22 0.020 0.87 0.23 -0.76 0.36 3.5 4 24 0.038 0.89 0.39 -0.98 0.39 6 4 26 0.057 0.94 0.55 -1.07 0.39 6 3 28 0.081 0.98 0.62 -0.93 0.40 6 1 30 0.080 0.96 0.52 -0.82 0.42 6 1 32 0.095 0.89 0.82 -1.65 0.04 6 7 34 0.065 0.90 0.76 -1.41 -4.57 6 7 36 0.015 0.80 0.40 -0.29 -0.61 2.5 3

Table 7-3 shows the same parameters as in Table 7-2 but for Case 2. The λD for Case 2 is clearly less than for Case 1 because the higher accuracy of the input wind field. But the improvement ratio is still good which indicates that it is meaningful to run the λ-model. In Figure 7-5 two different hours from Case 2 are plotted, hour 18 (a-c) and hour 30 (d-f). In row 1, the plots show the interpolated wind field which is used as input data. In the second row, the wind fields from the MIUU-model are shown and in the third row the results from the λ-model are shown. For hour 18 the result looks good. The only difference of importance is that the maximum wind speed in the MIUU-model result is found behind the top. For hour 30 the same problems as in Case 1 appear. But because the interpolated wind field includes information about the area with blocked air and that the λ-model generates the speed-up effect on the hilltop, the results look better than for Case 1.

32

10 20 30 40

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

Time =18, Height =67.4, αz =3

km

(c) Wind Speed λ − modelm/s

5

5.5

6

6.5

7

7.5

8

8.5

9

10 20 30 40

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

km

(b) Wind Speed MIUU modelm/s

5

5.5

6

6.5

7

7.5

8

8.5

9

10 20 30 40

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

km

(a) Wind speed Interpolated wind fieldm/s

5

5.5

6

6.5

7

7.5

8

8.5

9

10 20 30 40

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

Time =30, Height =67.4, αz =6

km

(f) Wind Speed λ − modelm/s

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

10 20 30 40

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

km(e) Wind Speed MIUU model

m/s

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

10 20 30 40

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

km

(d) Wind speed Interpolated wind fieldm/s

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Figure 7-5. Interpolated wind speed (a, d), MIUU-model results (b, e) and λ-model results (c, f) for hour 18 and 30 and level 8 (67 m).

33

7.4 Results at other levels The influence of the hill is largest close to the ground and decreases with height. This is described in Stull (1988), chapter 14.2.3. The adjustment of the wind field in the λ-model is also largest near ground. This is caused by the fact that the divergence is largest near the ground. When investigating the quality of the λ-model for different heights, it is found that the values of optimal αz increase with height. This increase is most dominant in Case 1, but is also seen in Case 2. The optimal αz for different levels for hour 18 is shown in Table 7-4. Table 7-4. Optimal αz for different levels and hour 18. Terrain used is Hill 1.

Level Case 1 Case 2 Ri 2 0.5 1 -0.02 3 2 2 -0.03 4 3 2 -0.06 5 4 2.5 -0.10 6 4 2.5 -0.16 7 5 2.5 -0.25

The difference in optimal αz for different heights may depend on the friction from the ground. The wind profile used for the input wind field is calculated with friction. But the λ-model adjusts the wind speed without accounting for the friction. That may be the reason for the overestimate of wind speed near ground in the λ-model and therefore a lower value of αz

is the optimum choice. (A lower value of αz gives a smaller adjustment in horizontal direction, see Section 8.) Another effect varying with height is the location relative to the hilltop of the wind maximum as found in the MIUU-model results. Near ground the maximum is found closer to the top of the hill. For example, at hour 18 the maximum in the MIUU-field is found one grid point (33, 31) closer to the top of the hill at low levels (below 12 m) than the layers above (12-250 m), where the maximum is found at point (33, 32). In the λ-model the wind speed maximum is found at point (31, 31) for all levels.

8. α-constants In Section 4.8 the theoretical background of the α-constants was discussed. In this section the effect of different α-constants will be studied.

8.1 Properties of α-constants Firstly, tests with αx = αy = αz = 1 and αx = αy = αz = 2 were performed. The results were identical. This leads to the conclusion that it is the ratio αh/αz which is the important parameter (αx = αy = αh). This is an important conclusion and consequently only αz has been varied in the following tests and αh is kept to 1 in all cases.

34

In Sherman (1978), αh=1 and αz=100 were used. But these values give unnatural results in the λ-model. Walmsley et al (1990) uses αh=2 and αz=0.25. Gao and Palutikof (1990), have made runs for a lot of α-values. They consider that αz=0.2 corresponds to very unstable and αz=10 (both with αh=1) to be used for very stable stratification. Different behaviors, as result of two different αz are shown in Figure 8-1. Simulations for the two different values of αz were made with the same hill and input wind data as in Section 6. The absolute values of the adjustment are calculated for each point of the domain. The adjustment decreases with increasing height. Figure 8-1 shows the height where the adjustment passes the threshold 0.3 m/s.

12

3

x 1041

2

3

x 104

0

500

1000

1500

X (m)

(a) Level for adjustment >0.3 αz=1

Y (m)

Z (

m)

12

3

x 1041

2

3

x 104

0

500

1000

1500

X (m)

(b) Level for adjustment >0.3 αz=4

Y (m)

Z (

m)

Figure 8-1a-b. Level with adjustment >0.3 m/s for αz=1 (a) and αz=4 (b) For the results shown in Figure 8-1a the value of αz was set to 1. The adjustment has two peaks, one in front of the hill and one behind. This adjustment belongs to adjustment in vertical wind speed. For the results shown in Figure 8-1b the value of αz was set to 4 (same as the simulation described in Section 6). The plot shows one peak above the hill. This peak belongs to the adjustment in the y-direction. The adjustment in Figure 8-1b also covers a larger area than in (a). This is caused by larger adjustment in the x-direction with αz=4. The results from (a) and (b) together show that a higher value on αz gives more adjustment in horizontal direction and that the adjustment goes up to a higher level with low αz. Another way to determine adjustment in the wind field for different αz is to calculate the difference between the maximum and minimum wind speed from the λ-model simulations in Section 7 and Case 1. The input wind speed at each height is equal for every point. After running the λ-model the difference between the minimum of horizontal wind speed in front of the hill and the speed-up above the top is dependent of the value of αz. This dependence for different heights is shown in Figure 8-2.

35

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 70

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10Maximum−Minimum as function of α

Max

imum

−M

inim

um (

m/s

)

αz

12.28 m67.4 m257.11 m875.42 m

Figure 8-2. The difference between maximum and minimum in wind speed from the λ-model for different levels. Terrain used is Hill 2. Figure 8-2 shows that the adjustment in horizontal wind goes to zero when αz goes to zero. The reason for this, as described above, is that the adjustment dominates in vertical direction for low αz. The figure also shows that the adjustment is largest near ground and decreases with increasing height. For the highest shown level (875 m) the adjustment has a maximum for αz=2. This is caused by the fact that a large value of αz gives only small adjustments in vertical velocity. This means that no horizontal adjustments are needed for high levels.

8.2 Choice of αz Because the lack of an obvious physical implementation of α-constants, these have to be empirically chosen. From the comparisons between the MIUU-model and the λ-model in Section 7 it is hard to see dependence between optimal αz and Ri (stability). The reason for this is that it is hard to determine the optimal αz for stable conditions when the λ-model results does not show the same wind speed patterns as the MIUU-model (see Figure 7-3). Instead, the quality of the input data is important. In Case 1, which uses input data with low quality, the optimal αz is around 4 and for Case 2 the optimal value is 3.5. These values are for Hill 2 with maximum terrain gradient 13.4 cm/m. For simulations with Hill 1, which has a smaller terrain gradient (3.6 cm/m), higher values for αz are needed for Case 1. The optimal value for this case and level 8 (67 m) is between 5 and 6. For Case 2 the optimal value is 3. For Hill 3, which has a maximum terrain gradient of 2.2 cm/m, the optimal value for Case 1 is between 3 and 4. Therefore, it looks like the optimal value for αz is not dependent on the shape of the hill. However, more simulations

36

with different shapes of the hill are needed to make a certain conclusion about the dependence between the shape and αz. The sensitivity for the choice of αz is however, not so big looking at average differences for the whole domain. For Case 1, Hill 1 and hour 18, the mean difference for αz=5 is 2.3%. If the value for αz instead is 4, the mean difference is 2.4%. The sensitivity for the maximum wind speed is higher. For αz=5 the maximum wind speed is 6.98 m/s at level 8 (67 m) and for αz=4 the maximum is 6.76 m/s. To summarize, the choice of αz is mainly dependent on the quality of the input wind field. A value for αz between 3 and 5, could be recommended. Any dependences of α on different properties, such as stability, need further investigations.

8.3 Improved use of α-constants In all the tests performed in this report, α has been treated as a constant. A method to improve the use of α would be to let it vary in space. As described earlier, the value of α determines the rate of adjustment. In Case 2, where the field has been interpolated from every tenth point, the quality of the input field varies in space. The quality is determined by how far the point is from the nearest input point. A point close to an input point should have a very small adjustment because it already has the “true” value, but a point in between needs some adjustment. This problem was discussed in Gao and Palutikof (1990), where the model COMPLEX was modified to treat the problem. The reason why NOABLE* was not modified in the similar manner was the complexity in making the field non-divergent. Having different weights for the points is only useful if the wind field “knows” the hill. If the input field does not “know” the hill, no input points are more accurate than the interpolated points in between. To examine the possibility to improve the model in this way, the model was set up with αx and αy in the following configuration:

⎥⎦⎤

⎢⎣⎡+⎥⎦

⎤⎢⎣⎡+= j

dCi

dCyx

ππα 2cos2cos1, (8.1)

C is the amplitude that α will vary with and d is the distance between the interpolated points. This function gives a field with a maximum at the chosen points from the MIUU-model and a minimum at the point most far away from the chosen points. The reason for using a trigonometric function is only for simplicity. The points used for interpolation are 0, 10, 20 etc, whereby no displacement is needed. A new version of the λ-model was developed for the test. But the only change made, was the ability to have a varying α. Eq. (4.14d) was still used for making the matrix. This leads to an error as, during the derivation of Eq. (4.14d), α was treated as a constant; dα/dn was set to 0. As a consequence the divergence will not be zero, but it was still judged to be meaningful to investigate whether the model would be improved by using a varying α.

37

The new version of the model is better to reproduce the field from the MIUU-model. This test is made for hour 18. When using αz=2.5 (which is the best from the former runs) and C=0.15 the new version gives the mean difference 0.87 % for level 8 (67 m) compared with 0.92 % for constant α. This gives an improvement ratio of 0.755 for the new version compared with 0.794 for the old one. If higher values of C are used, the field looks strange with circular regions of different wind speeds. One reason for the improvement is that the maximum wind speed now is just above the hill. In the new version the maximum is found at point (23, 20) compared with the MIUU wind field where it is found at (23,22). The magnitude of the maximum is somewhat too low (6.75 compared with 6.97) in the new model version which leads to a possibility to calibrate the parameters. The optimal αz is 3 for the improved model, based on the mean difference (improvement ratio 0.751). But this is not the α-value optimal to reproduce the maximum wind speed, which is αz=4. The divergence in the meaning of satisfying Eq. (4.14d) is of the order 10-5 compared to 10-15 for the old model version. This problem can be solved by modifying the theory behind Eq. (4.14d). But this leads to a much more complicated design of the matrix, which is out of the scope for the present work. Improved but small results are also reached for the night hours. The improvement ratio for the new version is 0.964 compared with 0.975 for the old. So the result from the λ-model still differs a lot from the MIUU-model.

9. Simulation – Aapua

9.1 Model setup This study is performed for an area in Norrbotten in northern Sweden. The center of the domain is a hill named Aapua. To the east of the hill a valley with the river Torne älv is found. The height of the hill is 350 meters above sea level and the difference in height between the top and the valley is around 300 meters. The terrain gradient in the area is moderate and the maximum gradient is 8 cm/m. The topography in the model domain is shown in Figure 9-1. The horizontal resolution for the test is 1 km.

38

1.82 1.825 1.83 1.835 1.84 1.845 1.85 1.855 1.86

x 106

7.41

7.415

7.42

7.425

7.43

7.435

7.44

7.445

7.45x 10

6 Terrain Aapua meter

100

150

200

250

300

350

Figure 9-1. The topography for the domain Aapua in Norrbotten. As input data simulations from the MIUU-model with 5 km resolution were used. The λ-model uses the same terrain map as the MIUU-model with the resolution 1 km. For simulations, the wind data with resolution 5 km are interpolated to a mesh with 1 km resolution, and the same vertical levels as the lowest 23 levels in the MIUU-model are used. In this test the vertical levels are 0, 2, 6.36, 12.43, 20.87, 32.61, 48.93, 71.59, 103.01, 146.51, 206.56, 289.19, 402.35, 556.31, 763.91, 1040.5, 1403.1, 1868.4, 2449.1, 3149.1, 3910.3, 4671.5, 5432.7 meters. The vertical wind in the terrain-influenced coordinate system is calculated from the terrain map and the horizontal wind field, with the condition that the vertical wind in the Cartesian system is 0 (see Eq. 4.8). The λ-model results are compared with the results from MIUU model simulations with resolution 1 km. The comparisons between the MIUU-model and the λ-model are performed for several simulations with different geostrophic wind directions and wind speeds. For runs with geostrophic wind from south east, comparisons are done for geostrophic wind speeds of 4, 9 and 14 m/s and at hours 12, 15, 18, 21, 24 and 36. For geostrophic wind directions from south and south west, tests are done with geostrophic wind speeds of 9 m/s and hours at 12, 18, 24 and 30. The radiation conditions used correspond to the conditions for October. For each direction and wind speed, simulations with the λ-model are made for αZ=0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 5, 6, which makes it possible to find out the optimal αZ for different conditions.

39

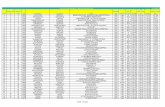

9.2 Results One problem that occurs in comparisons between the MIUU-model and the λ-model is that a horizontal displacement of the wind field between the model results are present. The wind field from the λ-model is located 1 grid point to the east of the wind field from the MIUU-model. This is probably the same effect as in the simulations in Section 8, where the wind speed maximum was found behind the top of the hill in the MIUU-model simulations. To make a fair comparison between the models, due to the wind pattern, the MIUU wind field is moved 1 grid point. This is only done in Table 9-1. In all other figures the fields have the original location. Table 9-1. Different quality parameters for geostrophic wind condition south-east 9 m/s. Level 8 (72 m) and hour 15. Pay attention to that the MIUU-model wind field is displaced 1 grid point to east. Hour

λD Ratio

inDDλ

Max λD

Min λD

Mean Wind Speed λ-

model

Mean Wind Speed

MIUU1 km

Optimal αz

for λD

Ri

12 0.033 0.90 0.33 -0.20 4.94 4.79 3 -0.12 15 0.032 0.87 0.37 -0.16 5.37 5.07 3 -0.02 18 0.033 0.88 0.56 -0.14 6.09 5.72 3.5 0.13 21 0.034 0.88 0.49 -0.16 5.96 5.71 4 0.13 24 0.038 0.88 0.49 -0.22 5.94 5.73 5 0.10 30 0.054 0.82 0.48 -0.27 5.85 5.39 6 0.06