Styrene

Transcript of Styrene

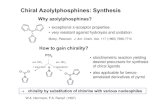

ι Key Chemicals

Styrene • Demand lagging capacity • Pricing weak • Exports relatively good

PRODUCTION/CAPACITY

Billions of lb

10 Production

| Capacity

III III 1975 1976 1977

HOW MADE Dehydrogenation of ethylbenzene made by alkylation of benzene or recovery from refinery streams

MAJOR END USES Various homo- and copolymers 80 % Styrene-butadiene rubbers 10% Unsaturated polyesters 8%

FOREIGN TRADE Imports—negligible Exports—currently strong, probably 10% of production

PRICE Volume contracts, 21 cents a lb with a temporary voluntary allowance of 1 cent. Spot market varies over a 1 to 2.5 cent-per-lb range lower than contract

VALUE Commercial value of total production, $1.3 billion in 1977

Styrene is nearing the end of a long change in its consumption pattern, which should hold at about the current end-use distribution. This change confirms that styrene has become a mature, large-volume chemical. As a result of maturity, forecasts of annual growth in styrene consumption are now half of what they were a decade ago.

In 1977, for example, styrene production might increase as much as 8 %, or some 500 million lb, over 1976 production of about 6.3 million lb. However, if growth this year runs around 350 million lb, the rate could come in at under 6 %. Such a percentage would be half of the rate of a decade ago, when production was recovering similarly from a recession.

The slackening in growth by no means comes about from a capacity shortage. In fact, a large amount of new capacity, 1 billion lb on nameplate, now is heading for full output at Oxirane's plant near Houston. Earlier capacity additions of 1976 already totaled more than 500 million lb. These earlier additions plus the Oxirane expansion set up the styrene segment of the chemical industry for years to come in meeting demand in the U.S. and abroad.

Many intricate factors are now at work on styrene capacity, not the least of which is the range of selling price. During the past year, the price has softened as rumors suggested for some time. The softness in price became clear with the recent widespread temporary voluntary allowances of 1 cent a lb. Export price is weakest, typical of any large-volume, widely sold chemical.

Working to further squeeze styrene producers with old plants are rising operating costs. How these operating costs relate to capital costs can provide important clues to lives of old styrene plants if selling prices remain level or increase only slightly. If replacement cost economics come into play on total production costs, then old and small plants could begin to be shuttered. But, special cases of market needs, raw material costs and availability, transportation costs, and accounting methods can cause old units to be kept operating. No industry source will take a stand on future capacity outlook without strong qualifications on energy costs—translate as world crude oil costs—and the outlook for the U.S. economy in general.

Although energy and raw material costs are important to styrene production economics, the operating rate also can make or break plant operation. If consumption of plastics holds up, most plants probably will have rates high enough to be kept running for at least the next year.

At this time, just about all styrene becomes either a homopolymer or a copolymer that eventually finds its way into consumers' hands. A large part of styrene polymer products are disposed of quickly. As disposable items these products generally are the lowest-cost materials that can do the job. Hence, competition from other polymers depends on their costs, which are not declining. The disposable markets for polystyrene thus are closely tied to consumer spending.

The durable goods markets for styrene polymers differ in that factors other than consumer spending are involved. Most important is the cost performance position relative to similar positions of other polymers. For example, if less weight of a more expensive polymer will do the job in an automobile part, a styrene polymer could be phased out.

The reverse is also true. One use of styrene that is growing faster than the average is in making unsaturated polyesters. An important part of the growth uses of these polyesters is in automobiles, boats, and housing, where they replace other materials. This outlet could be the only major use remaining with a double-digit growth rate, possibly up to 12% a year. But the use remains small, consuming less than 10% of styrene production for this year.

Still, polyesters could replace styrene-butadiene rubber as the second largest use of styrene. The reason is the extremely low growth in production of SBR in recent years. SBR's problem continues to be a combination of changes in tire and rubber product materials, in fabrication, and in vehicle driving habits of consumers.

The near-term prospects for styrene are more of the same. The growth in production during the next year will range from 6 to 8 % . Exports, now reasonably high—at about 600 million lb this year—will decline slowly even as the world economy improves, because more foreign capacity will start up. Prices are unlikely to slip much more as producers are near unprofitable selling now.

10 C&ENAug. 15, 1977

Key Chemicals

Vinyl chloride • Demand good • Capacity use up • Prices stable and up

PRODUCTION/CAPACITY

Billions of lb ο

• I

1975 1976 1977

HOW MADE Dehydrochlorination of ethylene dichloride made from ethylene and chlorine

MAJOR END USE Making homo- and copolymers, whose major uses are extrusions such as pipe, 55%; films 15%; coatings 10%; moldings 10%

FOREIGN TRADE Imports—negligible Exports—strong, to reach more than 500 million lb or about 10% of production

PRICES 14.5 cents a lb. No significant spot market

VALUE Commercial value of total production, $850 million in 1977

Vinyl chloride producers have ended worries over one problem and switched to another. No problem now exists in meeting expected demand for vinyl chloride for more than a year. But how to make money selling vinyl chloride in the face of rising costs is becoming increasingly more important.

Actually, vinyl chloride producers hardly qualify as worriers compared to producers of other major plastics monomers. Even with the cost problem, vinyl chloride has more going for it than almost any other monomer. It alone obtained a good selling price increase during the past year. Currently, it sells with the least price softness of any major monomer except butadiene.

In fact, things could have been much tighter. A year ago, the emission limit problem had vinyl chloride producers staggered. Estimates of operable capacity that actually could be run topped out in the low 8 0 % area. Yet demand was firming, and producers were gloomy about meeting it.

Some fresh capital changed all that. Vinyl chloride producers added investment to plants in many forms from employee protection equipment to sophisticated analytical networks. The result is that operable plant capacity has recovered to the old levels of 9 0 % or more. (Vinyl chloride's operating level can be below the average for the chemical industry, but this is due to technical problems such as corrosion, not emission trouble.)

This year and next, vinyl chloride production is expected to run more than 85% of rated capacity. Gains in demand this year likely will equal the small additions to capacity. Next year capacity will jump more than will demand. The reason is that Dow Chemical will have on stream its new vinyl chloride capacity at Plaquemine, La.—600 million lb more, to bring its total at that location to 1 billion lb annually. Then well into 1978, Diamond Shamrock expects to add another big unit with a capacity of 1 billion lb annually.

Exports of vinyl chloride have been strong but are expected to decline as some new units come on stream in various parts of the world. The reduction in exports will be available to the domestic market, if any new surge in demand should occur.

All this adds up to another good year for vinyl chloride in 1977 with prices expected to hold or move up. Some in

dustry sources expect price action this quarter, traditionally a strong one for sales, along with the second quarter. For practical purposes vinyl chloride units are running all-out now in contrast to a slower pace in the first quarter. No limits exist to this kind of operating level from the key raw materials, chlorine and ethylene.

Yet various plant outages such as one Dow experienced at its Oyster Creek unit near Freeport, Tex., in June worry users of derivative polyvinyl chloride (PVC) at a time when they, too, can sell nearly all of the fabricated products they can make. Hence, companies may try a half-cent-a-lb price increase toward the end of September to bring prices to the 15 cent-a-lb area.

On a list price basis, such an increase would be about 3.5%. If all of such an increase would accrue to producers, which it won't because of increased overhead costs, producers would get a big help in paying operating cost increases. Something will be left for capital costs, too, a healthy sign among the weak returns throughout much of the chemical industry.

If such a selling price increase goes through, or even a larger one, the curbing effect on sales won't be noticeable, according to some industry sources. True, the demise of large rates of growth for vinyl chloride could be blamed in part on price increases. But unless the new boost produces a large cost increase to users of PVC, PVC performance still will determine growth for vinyl chloride. For this year and the next few, vinyl chloride's production growth will run between 5 and 7% annually. A few end uses will grow faster, but many big uses will be held back by their sheer size.

Pipe, which could take as much as a third of vinyl chloride production this year, continues to be a strong outlet because of a healthier construction industry. However, this high base level plus vinyl chloride's lack of substantial inroads into construction materials, will keep down the future growth rate. A real breakthrough is needed in use of vinyl polymers in exterior siding and other uses in both residential and commercial buildings, one source suggests.

Most other uses of vinyl chloride polymers are highly segmented. In the aggregate they make vinyl chloride a big-volume monomer. But none can be counted on to return vinyl chloride's growth to the rate of the 1960's.

Aug. 15, 1977 C&EN 11

Production I Capacity

Key Chemicals

Propylene oxide • Demand growing slowly

• Capacity expanding

• Pricing under pressure

PRODUCTION/CAPACITY

Billions of lb

3.0 ^ ^ ^ Production WÊÊ Capacity

2.5

2.0

1.5 • I I 1975 1976 1977

HOW MADE

Chlorohydration of propylene and subsequent saponification with lime; peroxidation of propylene

MAJOR END USES

Flexible and rigid polyurethane foams 55 % ; reinforced unsaturated polyester fabricated products 20%

FOREIGN TRADE

Exports vary widely, could reach about 10% of production Imports—small, a bit more than 1 % of production

PRICES

25 cents a lb in quantity, including a temporary voluntary allowance of 3 cents. No significant spot market

VALUE

Commercial value of total production, more than $350 million in 1977

Propylene oxide will have to await new product developments for its next growth spurt. Meanwhile, in the next year or so, production will grow at a rate closely dependent on how the economy goes, probably about 8 % this year over 1976, or some 150 million lb.

Dependence of propylene oxide on the economy reflects the recent history of this rnajor-volume plastic raw material. In the past 15 years, fabricated polymers such as polyurethanes and polyesters based in part on propylene oxide have become important parts of the diverse range of consumer products from autos and bedding to refrigerators and yachts. Industrial uses are nearly as varied, though smaller in volume. Small volumes of nonpolymer uses of propylene oxide also go into consumer products such as food and cosmetics.

As new technical innovations came along, these propylene oxide derivatives moved into consumer markets with a rush, rapidly displacing older products. Rigid foam used as insulation in refrigerators and freezers is a classic example of this rapid shift.

All of these developments combined to provide high growth rates in demand for propylene oxide and a heady time for producers in the early 1970's. Then one plant expansion after another led to a surge in capacity during the past three years. Capacity additions, including one still being smoothed out by Oxirane, add up to a two-thirds increase in the three years between the beginning of 1975 and the beginning of 1978.

Unfortunately, demand for propylene oxide fell in the 1975 recession. Production that year actually declined more than 10% from the 1974 level.

Recovery was strong in 1976 and continues today, albeit at a slower pace. This year output likely will rise a bit more than half of the 1976 gain of some 275 million lb, assuming the economy remains in its current state of health. If the economy should expand more briskly for some unexpected reason, propylene oxide production could top 2 billion lb in 1977 for the first time.

Producers need this economic upswing. Capacity, even before Oxirane's midyear startup of 400 million lb, was large enough to hold the operating rate to less than 75%. Oxirane's addition is more than 2.5 times the consensus 1977 increase in demand for propylene oxide forecast by industry sources.

If the growth rate for propylene oxide

demand holds close to the current level, capacity now in place could suffice until the early 1980's. On the other hand, it might not, if some innovations in consumer products such as bedding, carpet backing, and auto parts result in big hikes in uses of polyurethanes.

Another important factor running in propylene oxide's favor is raw material availability. Most industry estimates on propylene forecast a comfortable situation for users over the next few years. The only difficulty would be temporary crimps on coproduct propylene output from the new naphtha-based ethylene plants at times of low ethylene production.

For now, prices of propylene oxide are under downward pressure. Temporary voluntary allowances, in effect, make actual prices up to 3 cents below posted prices.

How long these allowances will remain, no industry source will predict. Some sources point out that various cost increases in labor, raw materials, and energy are squeezing profit margins. These increases could result in a price increase of nearly 10%, or about 2 cents a lb, for propylene oxide and the equivalent for derivatives in a year's time, probably in the form of an end to part or all of the allowances. Such price increases will pass through the chain of products based on propylene oxide to retail prices for furniture, autos, boats, and many others. The increases at the consumer level likely will be small, for the weight of propylene oxide in most of these end products remains tiny, compared to the total weight.

Transportation products are forecast to consume slightly more than 20% of the propylene oxide production. Yet in this single largest use, the average per unit weight of propylene oxide made into various kinds of polyurethanes, polyesters, and other products probably falls under 40 lb. This volume includes sizable quantities that now go into soft molded unitized seats of polyurethane and into the various reinforced plastic parts under the hood, in the fender areas, and under the dashboard.

Transportation and housing-related products will continue to be a major growth area for propylene oxide, although some small, little known uses could get special attention if they take off. These uses include derivative propylene glycol in solvents, lubricants, plastics additives, and even pet food.

V 12 C&ENAug. 15, 1977