Cannabidiol Claims and Misconceptions - Squarespace · PDF fileCannabidiol Claims and...

Transcript of Cannabidiol Claims and Misconceptions - Squarespace · PDF fileCannabidiol Claims and...

3. MacGillivray, N. (2015) Sir William Brooke O’Shaughnessy(1808–1889), MD, FRS, LRCS Ed: chemical pathologist,pharmacologist and pioneer in electric telegraphy. J. Med.Biogr. Published online September 18, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0967772015596276

4. Moreau, J.J. (ed.) (1973)Hashish and Mental Illness (1845),Raven Press

5. Booth, M. (ed.) (2005) Cannabis: A History, Picador

6. Samorini, G. (ed.) (1996) L’erba di Carlo Erba: Per UnaStoria Della Canapa Indiana in Italia: 1845–1948, Nautilus

7. Kynett, H., ed. (1895) Cannabis indica. Medical and Surgi-cal Reporter (New York). 72, 1895, 562.

8. Musto, D.F. (1972) The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937. Arch.Gen. Psychiatry 26, 101–108

9. Mechoulam, R. and Gaoni, Y. (1967) Recent advances inthe chemistry of hashish. Fortschr. Chem. Org. Naturst. 25,175–213

10. Pisanti, S. (2009) Use of cannabinoid receptor agonists incancer therapy as palliative and curative agents.Best Pract.Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 23, 117–131

11. Pisanti, S. et al. (2013) The endocannabinoid signalingsystem in cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 34, 273–282

12. Bifulco, M. and Pisanti, S. (2015) Medicinal use of cannabisin Europe: the fact that more countries legalize the medici-nal use of cannabis should not become an argument forunfettered and uncontrolled use. EMBO Rep. 16, 130–132

13. MacCoun, R.J. and Mello, M.M. (2015) Half-baked – theretail promotion of marijuana edibles. N. Engl. J. Med. 372,989–991

ForumCannabidiol Claimsand MisconceptionsEthan B. Russo1,*

Once a widely ignored phytocan-nabinoid, cannabidiol now attractsgreat therapeutic interest, espe-cially in epilepsy and cancer. Aswith many rising trends, variousmyths and misconceptions haveaccompanied this heightened pub-lic interest and intrigue. This forumarticle examines and attempts toclarify some areas of contention.

CannabidiolCannabidiol (CBD) is a 21-carbon terpe-nophenolic compound exclusive to can-nabis after its decarboxylation from acannabidiolic acid precursor (Figure 1). Itis a pharmacological agent of wondrousdiversity, an absolute archetypal ‘dirtydrug’, encompassing analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiemetic,antianxiety, antipsychotic, anticonvulsant,

198 Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, March 2017, Vol

and cytotoxic effects (confined to malig-nant cell lines), which are mediated by awide variety of signaling mechanismsincluding activity on cannabinoid recep-tors, 5-HT1A, GPR55, GPR18, TRPV1,and other transient receptor potentialchannels (see [1,2] for more comprehen-sive reviews).

The newfound interest in CBD has beenaccompanied by an alarming number ofmischaracterizations that will be the focusof this forum article. These include appar-ent confusion as to the correct assignationof CBD’s psychopharmacological activity,particularly alleged sedative effects, itsmechanism of action as an antagonist atthe CB1 receptor, its legal status in com-merce, and its metabolic fate in humanadministration. Better understanding ofthese issues will be of great importancefor patients, recreational consumers,physicians, and legislators as they furtherconsider the role and disposition of thisversatile phytocannabinoid.

Misconception: Cannabidiol IsNon-psychoactive and Non-psychotropicCBD is frequently mischaracterized in lay,electronic, and scientific sources as ‘non-psychoactive’ or ‘non-psychotropic’ incomparison to tetrahydrocannabinol(THC), but these terms are inaccurate,given its prominent pharmacological ben-efits on anxiety, schizophrenia, addiction,and possibly even depression. Moreaccurately, CBD should be preferablylabeled as ‘non-intoxicating’, and lackingassociated reinforcement, craving, com-pulsive use, etc., that would indicate asignificant drug abuse liability [1].

Misconception: CBD Is SedatingSome early anecdotal literature cited a lowincidence of sedation after CBD adminis-tration, and contemporaneously, this sideeffect is frequently attributed to CBD.However, low to moderate doses are dis-tinctly alerting, as proven in its ability tocounteract sedative effects of THC, delaysleep time as documented via

. 38, No. 3

electroencephalography, and reduceTHC-associated ‘hangover’ [3]. Numer-ous modern studies, even those with sin-gle doses of 600 mg of oral CBD, innormal subjects have been free of seda-tive effects [4]. By contrast, CBD as Epi-diolex (an investigational cannabis extractwith traces of THC, other cannabinoids,and terpenoids) employed in very highdoses of 25 mg/kg/day or more to treatintractable epilepsy has produced seda-tion under conditions of polypharmacy,especially linked to elevated levels of N-desmethylclobazam when co-adminis-tered with clobazam, which resolves wellafter reduction of the dose of the latter [5].

Whereas pure CBD is not sedating, manyCBD-containing drug and hemp chemo-vars do display this liability. This is notattributable to CBD concentration perse, but rather to the predominance ofmyrcene in high titer in many commercialvarieties. Myrcene, a monoterpenoid, dis-plays a prominent narcotic-like profile thatis seemingly responsible for the ‘couch-lock’ phenomenon frequently associatedwith modern cannabis phenomenology[1]. Selective breeding of low myrcenechemovars reduces or eliminates this lia-bility, yielding cannabis plants or extractsthat are more suitable to the patient whomust also work or study (Figure 2).

Misconception: CBD Is a CB1

Antagonist Like RimonabantRimonabant, also called SR141617 orAcomplia, is a synthetic CB1 inverse ago-nist that was marketed briefly in Europe totreat obesity and metabolic syndrome. Itwas removed from the market due tonumerous serious associated adverseevents, including anxiety, suicidal ideation,nausea, and even de novo cases of multi-ple sclerosis [2]. This situation produced achilling effect on development programsfor other CB1 inverse agonists and evenextended to harsh scrutiny of the naturalcompounds, CBD and tetrahydrocanna-bivarin, which, in contradistinction, act asneutral antagonists at CB1. The mecha-nism of action of CBD seems, rather, to

Geranyl phosphate: olivetolate geranyltransferaseHO

OH

COOH

Cannabigerolic acid

OH

OH

COOH

Cannabidiolic acid

+

CBDA synthase

OPO3OPO3

Geranyl pyrophosphateHO

OH

COOH

Olivetolic acid (5-pentyl resorcinolic acid)

OH

OH

Cannabidiol

Decarboxyla�onvia heat, light,or aging

OH

OH

7-hydroxy-cannabidiol

Hepa�c

metabolism

Strong acid

(in vitro only) O

OH

Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinolic acidsynthase (THC)

Pure CBD crystals

Hemp fieldUniversityof Kentucky

Cannabis flower GW Pharmaceu�cals

CapitateglandularTrichomesGW Pharmaceu�cals

Precursors

Figure 1. Cannabidiol (CBD) Production, Biosynthesis, and Metabolism. CBD is biosynthesized in hemp or drug chemovars of Cannabis sativa, and isproduced in greatest concentration in capitate glandular trichomes in the unfertilized female flowering tops of the plant. Its main precursors are olivetolic acid and geranylpyrophosphate, which produce cannabigerolic acid and then cannabidiolic acid (CBDA) via catalysis by CBDA synthase, an enzyme co-dominant with D9-tetrahy-drocannabinolic acid synthase. Subsequently, decarboxylation via light exposure, heating, or aging results in CBD. In vivo, first-pass hepatic metabolism produces 7-hydroxy-cannabidiol, whose specific pharmacology has yet to be ascertained. While exposure to strong acids can produce an isomerization of CBD to tetrahy-drocannabinol (THC), this reaction does not occur in vivo in humans (all images by E.B.R.).

stem from negative allosteric modulationof CB1 [6], particularly in the presence ofTHC, and it produces none of the rimo-nabant-type adverse events [2].

Misconception: CBD Is Legal inAll 50 StatesIn keeping with its versatile pharmacologywithout associated drug abuse liability orserious side effects, CBD is an unsched-uled drug in most nations. This is not thecase in the USA, where, pharmacologynotwithstanding, CBD has been a for-bidden Schedule I agent with its own DrugEnforcement Administration (DEA) num-ber, and designation as a THC analog.In spite of this continuing prohibition,domestic commerce in CBD in one formor another is rampant in storefronts and on

the Internet, frequently accompanied byclaims that its extraction from hemp refuseis a legal process.While currently toleratedwithout federal prosecution as of this writ-ing, such practices may concentrate pes-ticides and other agricultural toxins [7],and are explicitly illegal under the Con-trolled Substances Act of 1970 [8],wherein, although possession of hempstalks and certain other plant parts arenot expressly forbidden, chemical extrac-tion of those parts clearly is. This ‘excep-tion to the exception’ is clear in text of theAct. An additional confound of Americanlaw is that, at a time when Epidiolexbecomes an approved pharmaceuticalagent and is necessarily assigned to a lessrestricted schedule, this same status willnot extend to CBD from other sources,

Trends in Ph

which must remain in Schedule I untilmeeting similar standards of efficacy,safety, and consistency. Only reclassifica-tion of CBD by the Food and Drug Admin-istration and DEA, or an act of Congress,would alter this scheduling discrepancyand continuing anomaly.

Misconception: CBD Turns intoTHC in the BodyThis false claim has been frequentlyinvoked online, and has gained currency,and perhaps even credibility, after publi-cation of a recent article [9], in which it wasdemonstrated that CBD could be con-verted into THC after prolonged exposureto ‘simulated’ gastric acid. While thisisomerization reaction has been knownfor decades, first reported with putative

armacological Sciences, March 2017, Vol. 38, No. 3 199

PhytoFacts™

Cannabinoids:Class: LXX3GType: FlowerSpecies: SATIVAxHarvest date: Not specifiedSample info: 150619PP11Test date: 16/03/09Test ID #: ABDC-160309_120

2.0%

10.9%Gen

eral

Cann

abin

oids

Arom

a &

flav

orPh

ytoP

rint™

Ento

urag

e eff

ects

∗

Lemon CBD

12.5%Terpenoids:

Moisture:

Ra�o of top two cannabinoids

Sweet Relaxa�on

Comfort

Focus

Energy

Inspira�onCalm

∗This varies with individual, close, and �me.

Fruity

Citrusy

Floral

Herbal

Piney

Aroma

0.11%

0.77%

0.15%

0.12%0.06%

0.04%0.19%

0.34%0.08%

0.00%0.13%

Terpinoleneα-phellandrene

β-ocimene

γ-terpineneα-pinene

α-terpineneβ-pinene

α-terpineolα-humulene

β-caryophylleneLinalool

Caryophyllene oxideMyrcene

FencholCamphene

CareneLimonene

Key: Flavor

Earthy

Camphor

Spicy

Tropical

CannabinoidCBDATHCATHCVTHCCBCCBDCBG

11.9%0.2%0.1%0.1%0.1%0.1%0.1%

Weight%

TotalCBD46.6

TotalTHC1.0

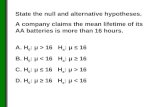

Figure 2. PhytoFacts of Type III Cannabidiol (CBD)-Predominant Non-sedating Chemovar ‘LemonCBD’. The PhytoFacts analysis of the chemovar reveals it to be a Type III, CBD-predominant plant, with THC-to-CBD ratio of 46.6:1, with high titers of limonene, caryophyllene, humulene, and alpha-pinene, but relativelylow myrcene content. Such a chemovar would be expected to be non-sedating, with good efficacy as an anti-inflammatory analgesic, also applicable to depression, anxiety, and treatment of addiction [1]. (Report courtesyof NaPro Research, https://phytofacts.info/). THC, tetrahydrocannabinol.

end products by Roger Adams in 1940,and with definitive structures by YehielGaoni and Raphael Mechoulam in the1960s, there is no evidence whatsoeverthat the reaction occurs in vivo in humans

200 Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, March 2017, Vol

[10]. First, no known enzyme exists thatcan catalyze such a bioconversion. Inaddition, pharmacokinetic and metabo-lism studies in human clinical trials refutesuch a reaction. In a double-blind

. 38, No. 3

placebo-controlled study of CBD in Hun-tington disease, 14 patients were admin-istered oral doses of 10 mg/kg/day(approximately 700 mg) over 6 weeks[11]. Mean plasma levels of CBD were5.9–11.2 ng/mL, but no plasma levels ofTHC (down to picogram sensitivity) werefound in any assays. Similarly, a morerecent randomized controlled studyexamined single oral doses of 600 mgof CBD or 10 mg of THC in 16 healthymales [12]. Whereas THC was highly sta-tistically significantly productive of adverseevents such as anxiety, dysphoria, posi-tive psychotic symptomatology, sedation,and intoxication, CBD was well toleratedwithout such THC manifestations. Moregermane to this debate, neither THC norits primary hepatic metabolite, 11-hydroxy-THC, was noted after CBDadministration. Effectively, there seemsto be no compelling evidence that CBDundergoes cyclization or bioconversion toTHC in humans.

Concluding RemarksCBD is an intriguing agent of unparalleledpharmacological diversity that is neverthe-less surprisingly benign in all its observedeffects. Its use has become widespread incertain geographical areas, particularly in‘legal’ states in the USA, and it is on thethreshold of becoming an approved phar-maceutical agent in intractable epilepsies.Given this current nouvelle richesse fol-lowing its long history of obscurity, it isincumbent upon the scientific and medicalcommunities to understand better themechanisms of action of CBD, its limita-tions, and particularly the myths and mis-conceptions that its meteoric rise inpopularity have engendered.

1PHYTECS, 20402 81st Avenue SW, Vashon, WA 98070,

USA

*Correspondence: [email protected] (E.B. Russo).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2016.12.004

References1. Russo, E.B. (2011) Taming THC: potential cannabis syn-

ergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects.Br. J. Pharmacol. 163, 1344–1364

2. McPartland, J.M. et al. (2015) Are cannabidiol and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabivarin negative modulators of the

endocannabinoid system? A systematic review. Br. J.Pharmacol. 172, 737–753

3. Nicholson, A.N. et al. (2004) Effect of delta-9-tetrahydro-cannabinol and cannabidiol on nocturnal sleep and early-morning behavior in young adults. J. Clin. Psychopharma-col. 24, 305–313

4. Borgwardt, S.J. et al. (2008) Neural basis of delta-9-tetra-hydrocannabinol and cannabidiol: effects during responseinhibition. Biol. Psychiatry 64, 966–973

5. Devinsky, O. et al. (2016) Cannabidiol in patients withtreatment-resistant epilepsy: an open-label interventionaltrial. Lancet Neurol. 15, 270–278

6. Laprairie, R.B. et al. (2015) Cannabidiol is a negative allo-steric modulator of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor. Br. J.Pharmacol. 172, 4790–4805

7. Russo, E.B. (2016) Current therapeutic cannabis contro-versies and clinical trial design issues. Front. Pharmacol. 7,309

8. Mead, A.P. (2014) International control of cannabis. InHandbook of Cannabis (Pertwee, R.G., ed.), pp. 44–64,Oxford University Press

9. Merrick, J. et al. (2016) Identification of psychoactive degra-dants of cannabidiol in simulated gastric and physiologicalfluid. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 1, 102–112

Trends in Ph

10. Grotenhermen, F. et al. (2017) Even high doses of oralcannabidiol do not cause THC-like effects in humans. Can-nabis Cannabinoid Res. (in press)

11. Consroe, P. et al. (1991) Assay of plasma cannabidiol bycapillary gas chromatography/ion trap mass spectroscopyfollowing high-dose repeated daily oral administration inhumans. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 40, 517–522

12. Martin-Santos, R. et al. (2012) Acute effects of a single, oraldose of d9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol(CBD) administration in healthy volunteers. Curr. Pharm.Des. 18, 4966–4979

armacological Sciences, March 2017, Vol. 38, No. 3 201