The Roman King as an Indo-European Distributer · The Roman King as an Indo-European Distributer...

Click here to load reader

Transcript of The Roman King as an Indo-European Distributer · The Roman King as an Indo-European Distributer...

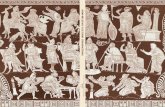

The Roman King as an Indo-European Distributer

Kanehiro Nishimura Kyoto University

In Latin there are a certain number of proper names, either theonyms or anthronyms,

that were inherited from Proto-Indo-European in a quite conservative way: e.g. Aurōra

(*h2éu̯sōs + -ā̆- [< *-eh2-]; Gk. ἕως, Ved. uṣā́ḥ), Cerēs (*kerh3-ḗs ← *kerh3- ‘nourish’;

Osc. kerrí, Umb. çerfe), and Nerō (< *h2ner-on-; Osc. niir ‘magister (?)’, Gk. ἀνήρ

‘man’, Ved. nar- ‘man, hero’). The goal of this paper is to add another case to the list,

that is, Numa, the well-known praenomen of the second Roman king, Numa Pompilius,

who is known to be of Sabine origin.

One may oppose the Sabine status (→ Italic, IE) of Numa with recourse to a form

attested in the Fibula Praenesina, that is, NVMASIOI (praen.), which could originally be a

creation in Etruscan; cf. Etr. Numasiana (gentil.), Numisiie (praen.?), etc. However, de

Simone (1991:207) suggests that the suffix -sie or the like seen in such examples in

Etruscan was not of Etruscan origin but borrowed from Italic. If so, the Sabine status

(→ Italic, IE) as a default value for Numa would also remain most likely, if there is no

compelling counterargument (see Schulze 1991:262, and Ernout and Meillet 1985:451).

By means of a well-known sound change, whereby *-o- became -u- before -m- (e.g.

umerus ‘shoulder’ [cf. Umb. onse, Ved. áṃsa- < *h2om- or *h3em-?] and numerus

‘number’ [cf. Gk. νόμος ‘custum, law’]), we can trace Numa back to Proto-Italic *nomā,

which can further be taken as *nom-eh2- (or *nome-h2-; see below) in IE terms with the

root *nem- in the o-grade. This form seems to be continued in Greek as νομή ‘pasture,

feeding, distribution’ (though not in Hom.). Verbal roots in the o-grade followed by the

suffix *-(e)h2- usually form feminine verbal abstract nouns, which also designate

concrete substantives (the so-called τομή-type ‘cutting; the end left after cutting, stump’

< *tomh1-). Latin also shows some such cases (see Weiss 2009:300): e.g. mola

‘millstone, mill’ (< *molh2-; cf. molō ‘grind’) and toga ‘covering, clothing’ (< *(s)tog-;

cf. tegō ‘cover’). Therefore, the IE identification of the Proto-Italic *nomā (> Numa) as

*nom-eh2- seems to be without problems.

A clear difference between νομή f. and Numa m. (< *nomā) lies in the gender. Since

the suffix *-(e)h2- was used to derive this type of nouns, the feminine gender is the

default value. However, the masculine gender is not excluded. As Weiss (2009:228)

describes, there are a certain number of masculine nouns in -a in Latin that originated in

“personifications of feminine abstracts, e.g. scrība originally ‘writing’ → ‘scribe’,

Nishimura 2

argicola ‘field-work’ → ‘farmer’.” Even in Greek, there are some s-less masculine

forms (dialectal), as adduced in Weiss 2009:228, such as Boeotian πυθιονῑ́κᾱ ‘victor at

the Pythian games’ and Northwest Greek Σϙόπᾱ (personal name). In view of these cases,

the masculine gender of Numa is not inexplicable, if one assumes that the personified

(or individualized) feminine abstract *nomā came to be used as a masculine personal

name. Alternatively, the suffix *-(e)h2- that underlies *nomā may have derived both an

animate substantive (typically masculine) and an abstract (typically feminine)

synchronically (see Nussbaum, forthcoming) from, probably, *nomó- (τομός-type)

‘distributing’; the derivative *nom-éh2- or rather *nomé-h2- has thus meant both ‘the

distributing (one)’ and ‘distribution’, the former of which is represented by Numa.

The above analysis allows us to associate Numa with Latin nemus ‘forest, wood (with

open glades and grazing-land)’ (< *‘what is distributed’; cf. de Vaan 2008:405), an exact

cognate of Gk. νέμος ‘wooded pasture, glade’. This connection would be quite

interesting from a standpoint of Classics and supportive of my interpretation of Numa.

This issue will also be discussed in the presentation.

References

de Vaan, M. 2008. Etymological Dictionary of Latin and the other Italic Languages.

Leiden / Boston: Brill.

de Simone, C. 1991. *Numasie-/*Numasio-: le formazioni etrusche e latino-italiche in

-sie/-sio-. Studi Etruschi 56:191–215.

Ernout, A., and A. Meillet. 1985. Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue latine: histoire

des mots. 4th, rev. and enl. ed. Paris: Librairie C. Klincksieck.

Nussbaum, Alan. J. Forthcoming. Feminine, abstract, collective, neuter plural: Some

remarks on each (expanded handout).

Schulze, W. 1991. Zur Geschichte lateinischer Eigennamen. New ed. Zurich:

Weidmann.

Weiss, M. 2009. Outline of the Historical and Comparative Grammar of Latin. Ann

Arbor / New York: Beech Stave Press.

![Roman odeon el[1]](https://static.fdocument.org/doc/165x107/557ea10dd8b42ac5658b47dc/roman-odeon-el1.jpg)