The Civil Reform of Diocletian in the Southern Levant

15

The Civil Reform of Diocletian in the Southern Levant Zvi Uri Ma‘oz The starting point of this endeavor is the uneven distribution of ‘boundary stones’ (λἰθοι διορΐζοντες, inscribed stones marking the border between the land of villages Χ and Y ; bornes cadestrales, bornes parcellaires ; henceforth: BS) across the territories of south- em Syria-Phoenice, northern Palaestina and Arabia, 295-297 CE. These boundary stones appear to be concentrated along a roughly southeast-northwest strip extending from the northern foothill of Mt. HaQran through the northern Hülah Valley. The rationale under- lying this strip, and the reason behind the placement of these markers in a sort of a chain along the length and width of the strip are the subject of this study. Maurice Sartre’s latest article on the subject ascribed these inscriptions to ‘fiscal re- forms’.1 Sartre’s approach, however, is unsatisfactory, since fiscal reforms cannot be limited to a specific territory. He himself noted the absence of BS from the southern HaQran as against their relative abundance further north. Consequently, he contended that the BS were connected with the mapping of specific units for taxation, units such as non-urban autonomic villages and other special places, i.e. sanctuaries and estates.2 David Graf, on the other hand, defined the problem in much clearer terms. Having noted that earlier land divisions (mostly centuriatio for veteran colonies) have been identified in aerial photographs in several places in Phoenicia, Syria, Palaestina and Arabia, he emphasized the ‘strange ... [phenomenon of the BS] skirting ... the province of Arabia’.3 In fact, except for very rare and isolated cases, the BS are missing in the bulk of the terri- tories covered by the Roman provinces in the Levant. (Were these territories exempt from fiscal reforms?) It should be emphasized here that the appearance of Diocletian’s Tetrarchic BS is the exception, not the rule. The presence of BS in one area, in contrast to their absence elsewhere, is a phenomenon that hitherto has not been explained satis- factorily. The explanation I shall offer pertains only to the BS found in southern Syria and northern Israel and does not relate to the nine BS, dated 297 CE, that were found in the limestone massif of northern Syria4 or to other BS found sporadically across the rest of the empire. 1 ‘La Syrie a livré depuis longtemps des bornes cadestrales que l’on a placées, ajuste titre, en rapport avec les opérations de bornage rendues nécessaires par les réformes fiscales de la Tétrarchie’, Μ. Sartre, ‘Nouvelles bornes cadestrales du HaQran sous la Tétrarchie’, Ktéma 17, 1992, 112-131 (112); see also, Α. Deléage, La capitation du Bas-Empire, (Paris, 1945; repr. New York, 1975), 152-157; F. Millar, The Roman Near East 31 BC-AD 337 (Cam- bridge, Mass., 1993), 535; contra W. Goffart, Caput and Colonate (Toronto, 1974), 44, 129-130. 2 Sartre (n. 1), 130. 3 D.F. Graf, ‘First Millennium AD: Roman and Byzantine Periods Landscape Archaeology and Settlement Pattern’, Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan, vii, (Amman, 2001), 475-476; based on Millar (n. 1), 535-544. 4 H. Seyrig, ‘Bornes cadestrales du Gebel Sim'an’, in G. Tchalenko (ed.), Villages antiques de la Syrie du Nord iii (Paris, 1958), 6-10. Scripta Classica Israelica vol. XXV 2006 pp. 105-119

Transcript of The Civil Reform of Diocletian in the Southern Levant

Zvi Uri Ma‘oz

The starting point o f this endeavor is the uneven distribution o f ‘boundary stones’ (λθοι διορζοντες, inscribed stones marking the border between the land o f villages Χ and Y ; bornes cadestrales, bornes parcellaires; henceforth: BS) across the territories of south- em Syria-Phoenice, northern Palaestina and Arabia, 295-297 CE. These boundary stones appear to be concentrated along a roughly southeast-northwest strip extending from the northern foothill o f Mt. HaQran through the northern Hülah Valley. The rationale under- lying this strip, and the reason behind the placement o f these markers in a sort o f a chain along the length and width of the strip are the subject o f this study.

Maurice Sartre’s latest article on the subject ascribed these inscriptions to ‘fiscal re- forms’.1 Sartre’s approach, however, is unsatisfactory, since fiscal reforms cannot be limited to a specific territory. He himself noted the absence o f BS from the southern HaQran as against their relative abundance further north. Consequently, he contended that the BS were connected with the mapping o f specific units for taxation, units such as non-urban autonomic villages and other special places, i.e. sanctuaries and estates.2 David Graf, on the other hand, defined the problem in much clearer terms. Having noted that earlier land divisions (mostly centuriatio for veteran colonies) have been identified in aerial photographs in several places in Phoenicia, Syria, Palaestina and Arabia, he emphasized the ‘strange ... [phenomenon o f the BS] skirting ... the province o f Arabia’.3 In fact, except for very rare and isolated cases, the BS are missing in the bulk of the terri- tories covered by the Roman provinces in the Levant. (Were these territories exempt from fiscal reforms?) It should be emphasized here that the appearance o f Diocletian’s Tetrarchic BS is the exception, not the rule. The presence of BS in one area, in contrast to their absence elsewhere, is a phenomenon that hitherto has not been explained satis- factorily. The explanation I shall offer pertains only to the BS found in southern Syria and northern Israel and does not relate to the nine BS, dated 297 CE, that were found in the limestone massif o f northern Syria4 or to other BS found sporadically across the rest o f the empire.

1 ‘La Syrie a livré depuis longtemps des bornes cadestrales que l’on a placées, ajuste titre, en rapport avec les opérations de bornage rendues nécessaires par les réformes fiscales de la Tétrarchie’, Μ. Sartre, ‘Nouvelles bornes cadestrales du HaQran sous la Tétrarchie’, Ktéma 17, 1992, 112-131 (112); see also, Α. Deléage, La capitation du Bas-Empire, (Paris, 1945; repr. New York, 1975), 152-157; F. Millar, The Roman Near East 31 BC-AD 337 (Cam- bridge, Mass., 1993), 535; contra W. Goffart, Caput and Colonate (Toronto, 1974), 44, 129-130.

2 Sartre (n. 1), 130. 3 D.F. Graf, ‘First Millennium AD: Roman and Byzantine Periods Landscape Archaeology

and Settlement Pattern’, Studies in the History and Archaeology o f Jordan, vii, (Amman, 2001), 475-476; based on Millar (n. 1), 535-544.

4 H. Seyrig, ‘Bornes cadestrales du Gebel Sim'an’, in G. Tchalenko (ed.), Villages antiques de la Syrie du Nord iii (Paris, 1958), 6-10.

Scripta Classica Israelica vol. XXV 2006 pp. 105-119

THE CIVIL REFORM OF DIOCLETIAN IN THE SOUTHERN LEVANT106

Damascus t

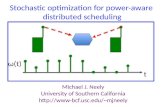

Ο Short version Full version - Lucius and Akakius

Full version - Marius Felix Δ Full version - without name of censilor

Full name in Palaestina Cily

. /P h o e n i c e! ·

* Ρ aneas S o * * o Q I Î l i ' Ο 0 11Γ.ι / 2 4 A

Δ-1 7, w / es-Sanameîn / el-H ara

Trachonitis

/ /

5— Raftd Gaulanitis j l e s t i n a j

Aaaranitis 34 A

© Moshe Hartal Ο 5 10 15 20 ,

Ι Paneas 11 Lehavot Habashan 21 Jermane 3 1 RçleTmeh el-Sharqïyyeh 2 Giser Ghajar 12 Lehavot Habusltn 22 Dârejah 32 Mleltiat el-‘Atash 3 Ma‘ayan Barukh 13 Lehavot Habashan 23 Ghabagheb 33 MleThat SharqTyyeh 4 Tel Tanim 14 Buq‘atS 24 ‘AqrabJI 34 Between SuweTdS and ‘AtTl 5 Shamir 15 QuneTtra 25 Khabab 35 AhmadTyye 6 Shamir 16 QuneTtra 26 BasTr 36 Afiq 7 Shamir 17 QuneTtra 27 Inkhel 37 Afiq 8 Shamir 18 Falim 28 SimlTn 38 Afiq 9 Shamir 19 ‘Eshshe 29 Namer 39 Kefar Haruv 10 LehavotHabashan 20 JisrTn 30 Jflneyneh 40 Kefar Haruv

The Political and Administrative Background

In the course o f the Tetrarchic reforms (including divisions and further segmentation of the provinces: 285/6, 293 CE5), Diocletian became the Augustus of the Eastern empire, which he ruled from Nicomedia in northwestern Asia Minor.6 Apparently Diocletian’s

Diocletian cut the province into fragments: provinciae quoque in frusta concisae (Lactantius DMP vii.4, ed. J.L. Creed [1984], 13). There is no ancient continuous narrative on the reign of Diocletian (284-305 CE). See provi- sionally W. Seston, Dioclétien et la Tétrarchie (Paris, 1946); Μ. Rostovtzef'f, The Social and Economie History o f the Roman Empire (2nd ed. rev. by Ρ.Μ. Fraser) (Oxford, 1957), 502-532 (= D. Kagan (ed.), Problems in Ancient History — The Roman World [New York and London, 1966], ii, 396-413); Α.Η.Μ, Jones, The Later Roman Empire 284-602 (Oxford, 1964), 37-76; i .D. Bames, The New Empire o f Diocletian and Constantine (Cambridge, Mass., 1984); Μ. Grant, The Collapse and Recovery o f the Roman Empire (London, 1999),

107ZVI URI ΜΑ'ΟΖ

political and administrative efforts were aimed not only at gaining a tighter grip over the provinces and their revenues, but also, and perhaps more importantly, were an attempt to assist local populations by concentrating closely on each region or province. Α possible example of such a localized approach is the placement o f boundary stones in the Levant.

Did the emperor ever set foot in the Levant and was he personally involved in the BS project? It is certain that Diocletian visited the Levant in 290 CE. His trip to Syria (in- eluding Antioch, Emesa, Laodicea and Paneas [see below]) and the campaign against the Saraceni will have lasted about two months.7 Several ancient Jewish writings mention Diocletian in conjunction with Apamea, Emesa (Homs), Tyre and Paneas, and these sources — which in my view are based on a historical kernel8 — may very well be re- lated to the 290 CE trip. It should be emphasized, however, that the emperor sojourned in Syria-Phoenice, not in Palaestina.

The essential Jewish texts are as follows:

: ). , ( : , (, ... . . ... )

It is written: He [God] founded it on seas and established it on rivers (Ps. 24:2): Seven seas surround Eretz Israel: the Great Sea ... the sea of ΡΜΥΥ’ [Apamaea] and there will be the sea {viz. lake, reservoir] of HMS [Emesa, modern Homs], DWKLYTYANWS [Diocletian] made rivers flow and made it [viz. the lake of Emesa]. (yKetubot 12:3, 35b)

There is no real reason to doubt this information and this leads us directly to the main issue o f this paper: Diocletian’s preoccupation with land development — in this case, the irrigation of arid zones. Our next bit of Talmudic evidence relates to the economic boost

39-43; S. Williams, Diocletian and the Roman Recovery (London, 1985). The most recent and detailed treatment of all the aspects of Diocletian’s regime known to me is in Hebrew: Moshe Amit, A History o f the Roman Empire (Jerusalem, 2002), 789-824. According to scholars, Diocletian was in the East several times: he has been assigned trips to Persia in 288 and 293 CE. to Egypt, and possibly to Nicomedia (293-303 CE). See Amit (n. 6), 793-797 and B. Isaac, The Limits o f Empire (2nd revised edition; Oxford, 1990), 73 and 278 (who suggests that there was a mutiny in Egypt). Isaac (ibid., 437), places Diocletian at Antioch in the winters of 287/8 and 288/9 CE and situates him there permanently from 299 through 303 CE. I have not been able to find any supporting evidence for Diocletian’s pre- sumed visits to Palestine in 276 and 297-8 CE (D. Sperber, Roman Palestine, 200-400: The Land [Ramat Gan, 1978], 157, n. 44), or in 286 CE (Μ. Αν-Yonah, The Jews Under Roman and Byzantine Rule [Jerusalem, 1984], 127). Despite the disagreements on Diocletian’s movements in the East, all scholars appear to assign him a sojourn in the northern Levant in the spring-summer of 290 CE. See Isaac (ibid.), 73, 437; Millar (n. 1), 177-179; Barnes (n. 6), 51, who note that in 290 CE Diocletian issued rulings from Antioch (May 6th, Frag. Vat. 276m), Emesa (Hôms; May 10th, CJ 9.41.9) and Laodicea (LattaqTyye; May 25th, CJ 6.15.2[28]). See too Pan. Lat. 11(3).5, 4; 7.Γ They suggest that Diocletian was in Syria, possibly fighting against the Saraceni. Barnes (ibid.), puts the fighting in May-June, because Diocletian was already at Sirmium on July 1st. See Α.Μ. Rabello, O n the Relations between Diocletian and the Jews’, JJS 35, 1984, 147- 67; Α. Marmorstein, ‘Dioclétien à la lumière de la littérature rabbinique’, REJ 88, 1932, 19- 43.

THE CIVIL REFORM OF DIOCLETIAN IN THE SOUTHERN LEVANT108

Diocletian was aiming to give the Levant, for we hear of the emperor’s involvement in a trade fair at Tyre.

.[...] [] : ' ,( . ' :

) , ,

R. Simeon b. Yohanan sent [and] asked R. Simeon b. Yozadak: Don’t you check the fair of Tyre, what it is? ... [He] went and found [that] it was written [= inscribed] there: DYKLTY’NWS [Diocletian] the king donated this eight day fair of Tyre for the GD’ [viz. genius] of my brother ’RKLYS [viz. Maximianus]. (yAvoda Zara 1:4, 39d)9

At the fair, goods were exempt from taxation and that surely stimulated business. How- ever, since the fair was dedicated to idolatry (the genius o f Maximianus), Jews were forbidden to attend it.

Two Talmudic texts point to Diocletian’s connection with Paneas:

, , : . : . ). , (' [...], .

DYKLYTY’NWS [Diocletian] oppressed ( ’a'ik) the sons [inhabitants] of PNYYS [Paneas]. They said to him: We are going [away, fleeing]. Α sophist said to him: They will not go [away], and if they will go [away], they will return... (yShev 9:2, 38d).

Paneas belonged to Syria-Phoenice (not Palaestina) and its population has always been overwhelmingly non-Jewish.10 However, in this source we get the first indication o f a possibly close relationship between Diocletian and this city (more below). We also find:

[...] . [...] [...] . ' -) , ].(' [

DYKLWT [Diocletian] ... became king, he went down to PMYYS [Paneas]. He sent let- ters to the Rabbis [saying]: You will appear before me immediately at the end of the Sabbath ... and Rabbi Yudan the Patriarch and Rabbi Samuel BarNahman went down on their way to bathe in the public bath [δημσιον] of Tiberias. An angitris (=’Αργονατης)

J.C. Greenfield, π Aramaic Inscription from the Reign of Diocletian Preserved in the Pal- estinian Talmud’, Atti 11 del Congresso Internazionale di Studi Fenici e Punici II, Roma, 1991, 499; Millar (n. I), 176. For a meeting between Diocletian and a Jew at Tyre, compare yBerachot 3:1, 6a: ‘... When the king Diocletian arrived here, Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba was observed walking over [impure] graves of Tyre to see him’. Jewish leaders apparently went out of their way to meet the ruler; see below for a possible meeting at Paneas. For the lan- guage of the inscription see also S. Lieberman, Studies in Palestinian Talmudic Literature (Jerusalem, 1991), 445-448 (Hebrew); J. Geiger, ‘Titulus Crucis’, SCI, 1996, 203-205.

10 Z.IJ. Ma'oz ‘Banks’, 137-13 in Ε. Stem (ed.), The New Encyclopedia o f Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land (Jerusalem and New York, 1993) (hereafter NEAEHL)\ G. Holscher, ‘Banias’, PRE 36 (1949), col. 594 sqq.

109ZVI URI ΜΑ'ΟΖ

appeared before them... at the end of the Sabbath he took them and carried them [to Dio- cletian at Paneas], (yTer 8:11, 46b-c)u

I contend that this last legend has a historical kernel. Diocletian was in the Levant in 290 CE and travelled as far south as Tyre. Paneas was in the hinterland o f the Phoenician coastal cities and on the main route to Damascus. Our previous source told o f the em- peror’s personal involvement with the taxation of Paneas. It is, therefore, highly likely that during his stay at Paneas, Diocletian summoned the leaders o f the Jewish commu- nity, who were located only about 65 km away, at Tiberias. Our legendary narrative points to the possibility of a meeting between the emperor and the Jewish leadership which took place, in all likelihood, at Paneas in the late spring o f 290 CE. The tale may even hint at a residence o f the emperor in Paneas (below, p. 117).

Diocletian toured the Levant again in 300-302 CE.11 12 As we shall presently see, the boundary stones were set, according to the inscriptions they bear, in the years 295-297 CE. Diocletian was not present in those particular years in the Levant and clearly did not supervise the erection o f the BS personally. However, he could have conceived the pro- ject and ordered the execution of the project himself while he campaigned in Syria- Phoenice some years earlier.13

The Land Reform

Along with the administrative changes came a tighter grip on the economy. It is most evident in the monetary reform and the empire-wide order regarding maximum price tariffs and salaries.14 The emperor could not much influence natural factors beyond his control, such as drought and plagues, other than offering post factum assistance,15 and consequently he devoted his efforts to combating inflation (through the list o f maximum prices), reorganizing the monetary/currency systems and attempting to form an equal basis for agricultural taxation. Lactantius provides a detailed description o f the kind o f

11 The Aramaic text is edited by Y.Z. Eliav, Mituv Teveria 10, 1995, 25 (Hebrew); my English translation is based on that of Yaron Zvi Eliav and David Rokeah. For the miraculous mari- time voyage from Tiberias to Paneas, see Z.IJ. Ma‘oz, ‘Roman War-Ships on Coins — Voyages on the River Styx’, INJ 16, 2007 (forthcoming).

12 Eusebius testified that he first set eyes upon the young Constantine in Caesarea, Palestine: ‘We knew him ourselves as he traveled through the land of Palestine in company with the senior Emperor, at whose right he stood’, (VC I, 19 [ trans. Cameron and Hall, 1999, 77). Millar (n. 1), 179, posits a trip of Diocletian and his entourage (comitates) to Egypt through Palestine between the years 300 and 302 CE on the basis of Eusebius; Isaac (n. 7), 290 ad- duces papyri dated 298 CE which tell of preparations for that royal visit.

13 Since, as we argue below, the BS indicate a land reclamation and settlement project, the emperor’s personal involvement is highly plausible; see below, p. 114.

14 Millar (n. 1), 180-189; Α. Cameron, The Later Roman Empire, 284-430 (London, 1993), 193-194: Edictum de maximis pretiis 301 or 303; H. Blumner (ed.), Der Maximaltarif des Diokletian (Berlin, 1958); S. Lauffer (ed.), Diokletians Preisedikt (Berlin, 1971); E.R. Grazer, Appendix, in: T. Frank, An Economic Survey o f Ancient Rome, v (Baltimore, 1940; repr. Patterson, N.J., 1958), 308-421; Amit (n. 6), 810-812; Cameron (ibid.), 38 notes, among others, that the edict was not effective for long.

15 Sperber (n. 7), 70-99; but see the review of Μ. Goodman, JRS 70, 1980, 35-36.

THE CIVIL REFORM OF DIOCLETIAN IN THE SOUTHERN LEVANT110

census undertaken by Diocletian: ‘Fields were measured out clod by clod, the vines and trees were counted, every kind of animal was registered, and note taken o f every member of the population’.16 Α later legal textbook describes the process (emphasis mine):

...at the time of the assessment there were certain men who were given the authority by the government; they summoned the other mountain dwellers from other regions and bade them assess how much land, by their estimate, produces a modius of wheat or barley in the mountains. In this way they also assessed unsown land, the pasture land for cattle, as to how much tax it should yield to the fisc.17

According to Jones, ‘In the Eastern provinces Diocletian seems to have registered only the rural population, the rusticana plebs, quae extra muros posita capitationem suam detulit, as he puts it in a constitution addressed to the governor o f Syria (in other prov- inces urban population was included)’.18 It is important to emphasize here that the boundary stones operation began in 295 CE, that is, two years before the general empire- wide census of 297 CE and seven years after the initial 287 CE census about which we know next to nothing. It is likely, therefore, that our local BS had no connection, or only a peripheral relation, to the agricultural fiscal reform.

Did the population under Diocletian’s rule face a problem of a severe shortage of available cultivable land? This question is o f utmost importance for our inquiry. The answer, however, is not unequivocal, for we have two seemingly opposite testimonies. Lactantius relates:

The number of recipients began to exceed the number of contributors by so much that, with farmers’ resources exhausted by the enormous size of the requisitions, fields became deserted and cultivable land turned into forest. (DMP vii, 3; trans. J.L. Creed [1984], 13)

In the course o f the mid-third century, cultivable land changed its status from that o f free property owned by small village farmers to that concentrated in the hands o f rich land- lords. The phenomenon engulfed all the Mediterranean provinces, including Palaestina.19 Therefore, our next bit of contemporary evidence does not necessarily contradict Lactan- tius, who may have described an ongoing process rather than the final status of land in the provinces. According to the Babylonian Talmud, new generations o f farmers looked in vain for fields to till, to the extent that a contemporary Palestinian sage, R. ’EYazar b. Pedat (of Tiberias, floruit circa 250-279 CE), states the following:

( ], [ ' ’ , : )

16 DMP xxiii. 2 (trans. i.L. Creed [1984]), 37. Even though the description pertains to Galerius’ census of 307, most interpreters believe it also holds true for Diocletian’s general census of 297, and could perhaps apply to the first census of 287 CE as well. See Amit (n. 6), 806-807; Deléage (n. 1), 148-162.

17 Syro-Roman Law Book exxi FIRA II., 796 (trans. Α. Cameron [1993]), 36. 18 Jones (n. 6), 63. 19 Α.Η.Μ. Jones, ‘Census Records of the Later Roman Empire’, JRS 43, 1953, 49-64; Sperber

(1978), 150-152, 187-203.

I l lZVI URI Μ Α Ζ Fields are only given to the ba'alei Zero'ot, as it is written: ‘The man of the arm (ve ’ish zero'a i.e. a mighty man) to him the earth [and the exalted one shall dwell in it]’ (Job 22:8). (bSanhedrin, 58b)20

Daniel Sperber noted that ‘it is surely significant that in the whole of Diocletian’s very lengthy and detailed Edict o f Maximum Prices, which was intended to reduce inflated costs, the prices of land are never mentioned’.21 Land may not have been a market prob- lem by the time o f the edict of 301 CE, but could have been an issue for the previous generation. Be that as it may, Diocletian’s keen interest in land issues is demonstrated by his introduction o f a new land unit for taxation purposes, the iugum, and also by his leg- islation dealing with the problem of land being sold (or bought) too cheaply.·22

Building Activity

Rulers have always known that building operations are not only everlasting memorials to their glory, but also a powerful stimulus to a lagging economy. Hence Diocletian, appar- ently a devoted student of the several great Roman emperors who preceded him, did not neglect this area of activity. Lactantius tells us o f his passion for building the new capital city Nicomedia (DMP vii, 8-10; trans. J.L. Creed [1984], 13) and it is highly unlikely that the capital was the only city built by the emperor.

We have already adduced sources relating to the construction of reservoirs at Apamea and Emesa, the regulation of the trade-fair at Tyre and perhaps the building of a palace at Bâniyâs/Paneas (to which we shall return). At this juncture, it is important to note Diocletian’s emphasis on the empire’s outskirts. In addition to his fortifications along the Persian frontier, it is clear, as five inscriptions (to date) reveal, that he was in- volved in the construction of legionary camps and roads along the desert frontier in the provinces of Arabia and Syria. According to the not too reliable 6* century CE historian John Malalas, Diocletian ‘built a chain of forts along the frontier from Egypt to Persia, and posted limitanei in them, and appointed commanders to guard each province with forts and numerous troops’. Furthermore, special efforts were made to integrate the semi- nomadic Arab tribes into the defense of the eastern frontier.23

If we bear this in mind, as well as Lactantius’ testimony on Diocletian’s passion for building, it is likely that the emperor was also personally involved in the details of build- ing and settlement activities that took place in the Near East. Diocletian may well have had a say in the positioning of the boundary stones, even though our sources reveal that

20 Translated by Sperber (n. 7), 128; see in general his chap. IV. 21 Sperber (n. 7), 158. 22 CJ 4.44.2; 4.44.8; Goffart (n. 1), 3 Iff.; Sperber (n. 7), 159; Frank (n. 15), Appendix to Vol.

5; Lauffer (n. 15). 23 Malalas Chronicon, 12, 38; trans, by Williams (n. 6), 95; Isaac (n. 7), 164-167; G.W. Bow-

ersock, Roman Arabia (Cambridge, Mass., 1983), 106-109, 138-147; Α. Lewin, ‘Dali’ Euphrate al Mar Rosso: Diocleziano, 1’esercito e i confini tardo-antichi’, Athenaeum 78, 1990, 141; id. ‘Diocletian: Politics and limites in the Near East’, in: Ρ. Freeman et al. (eds.), Limes XVIII: Proceedings of the ΧΙ ΙΙ International Congress o f Roman Frontier Studies held in Amman, Jordan (September 2000) (BAR International Series 1084 [I]) (Oxford, 2002), 91-101; I. Shahid, Rome and the Arabs: A Prolegomenon to the Study o f Byzantium and the Arabs (Washington D.C., 1984).

THE CIVIL REFORM OF DIOCLETIAN IN THE SOUTHERN LEVANT112

the BS operation was carried out between his visits, five years after he left Syria and two years before his empire-wide census.

The Number of Boundary Stones and their Locations: The Frontier

In comparison to Ariel Lewin’s 2002 assessment of Diocletian’s military operations on the eastern imperial frontier from the Euphrates to the Red Sea, the scope o f the BS is severely limited. There are only 41 Boundary Stones known to date in the entire 6700 sq. km research area.24

Several BS bear inscriptions that date them not only to the Tetrarchic era, indicated by the names of the rulers, but also specifically to 295-297 CE. The fullest inscription formula appears many times and can be exemplified by the stone from Gisr Ghajar, north of the Hülah Valley:

Διοκλητιανς κα'ι Μαξιμιανς Σεβ(αστοι) κα Κωνστντιος και Μαξιμιανς Κσαρες λθον διορζοντα γρος ποικου Χρησιμιανο στηριχθνε κλευσαν φροντιδι λιου Στατοτου το διασημ(οττου)

Diocletian and Maximian, Augusti, and Constantius and Maximian, Caesars, ordered a stone to be fixed marking the boundary of the fields of the colony Chresimianus, under the management of the most honourable Aelius Statutus.

Except for six instances, all the BS form a sort o f an interwoven complex chain; in other words, they are distributed (Map l)25 not on a single straight line, but in clusters on a curve. The six deviations include three BS that were found immediately east and south of Damascus, and the other three immediately east and south o f Hippos. The remaining BS were discovered within an elongated, roughly straight strip 112 km long and only 15 km across. It begins in the SE at Junemeh (5 km east of Saqâ-Maximianopolis, at the north- em foot o f Mt. Haflran/Jabal ad-Druze) and terminates in the NW near the Bridge over the Hasbani River at Gisr Ghajar (in accordance with the recently found inscription at Tel Tanim-Tell el-Wâwïyât, just east of Kiryat Shmonah at the eastern foot o f the Moun- tains of Galilee).26 The strip is approximately 15 km across, for example between Namer and Ghabagheb in the northern Haüran, or between Buq‘ata in the northern Golan27 and the group on the east edge o f the Hülah Valley. Thus, the entire territory under consid- eration has an area of ca. 1700 sq. km. By comparison, the Haüran, as a hypothetical

The fullest list is in Y. Ben-Efraim, The Boundary between the Provinces o f Palaestina and Phoenicia in the Second and Third Centuries in the Central Golan Heights (ΜΑ thesis, Bar- Ilan University, 2003), 12, 16, Map 3 (Hebrew). See too D. Syon and Μ. Hartal New Tetrarchic Boundary-Stone from the Northern Hula Valley’, SCI 22, 2003, 238-239, Table 1 ; L. Di Segni, Dated Greek Inscriptions from Palestine from the Roman and Byzantine Pe- riods (Ph.D. Thesis, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1977), 43-47, 148, 158-173, 184-187; Μ. Hartal, The Land o f the Ituraeans: Archaeology and History o f Northern Golan in the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine Periods (Qazrin, 2005), 361-362, Map 19 (Hebrew); Thirty-seven BS were already listed by Millar (n. 1), 540-544.

25 Courtesy of Moshe Hartal. 26 Syon and Hartal (n. 24). 27 R.C. Gregg and D. Urman, Jews, Pagans and Christians in the Golan Heights (Atlanta,

1996), 285-286, no. 240.

113ΖVI URI Μ ΑΖ

rectangle cut diagonally by our strip, comprises ca. 6700 sq. km. (77 km from Damascus to Dar‘à [Edre‘1] and 87 km across, from Junelneh, at the northern foothill o f Mt. Hafl- ran, to the Jordan River).

The BS strip is closely related to the provincial borders o f Arabia and Palaestina in the south and Syria-Phoenice in the north. The strip either includes the provincial border (mainly in the Hauran sector), or is tangential to it (in the Golan-Hülah Valley sector). While the exact borderline is not known, the BS are divided, according to the names o f their censitores, between the Roman provinces in the area as follows: 23 in Syria- Phoenice, 12 in Arabia and 6 in Palaestina. Although this difference in number may, at first glance, appear to be simply an accident of recovery, there may well be a connection between the BS distribution and the frontier.28 The BS strip was not meant to demarcate the border between the provinces on the ground. Their texts specifically state that their function is to separate the lands of two villages (with several exceptional cases dealing with sanctuary or estate properties). Nevertheless, the proximity o f these stones to the suggested borderline (for we lack the data to delineate it on a map) appears not to have been accidental.

The key to begin unlocking the ‘secrets’ of the strip is its environmental character — an unpopulated, or sparsely occupied, fringe zone. In 1886 Gottlieb Schumacher wrote:

‘According to the nature of the soil, the Jaulan may be divided into two districts: (1) stony in the northern and middle part, (2) smooth in the south and more cultivable part. ...Stony Jaulan (esh-Sharah, el-Quneitrah and the upper part of ez-Zawiyeh esh-Shurkiyeh) is an altogether rough and wild country [emphasis mine], covered with masses of lava which are poured out from countless volcanoes and spread in every direction. Although of little use agriculturally, it is the more valuable for pasturage... Wherever between the hard solid basaltic blocks there is a spot of earth, or an open rift visible, the most luxurious grass springs up both in winter and spring time, and affords the richest green fodder for the cat- tie of the Bedawin’.29 30

A hundred years later Francis Hugeut wrote:

‘(Test sur cette coulée, la plus récente de la région, qu’est construit le site de Shahba, au contact de trois paysages relativement contrastés. Limitée au Sud par un talus...A. la dif- férence du Leja qui est ... constitué de pahoehoe [extremely thin and liquid lava] ... il s’agit ici d’un aa [thick, more solid lava]: c’est une zone chaotique ... encombrée de blocs de lave scoriacée et friable, constituant parfois des aiguilles qui rendent la progression dif- ficile. ... Ce site a été utilisé pour l’édification d’un barrage, actuellement abandonnée. Un des derniers épisodes de la formation du Tell Shihan a également modifié le cours du wadi: un petit niveau alluvial ....3°

28 The possible connection was noted by Seston (n. 6), 374-376, map following 374; Deléage (n. 1), 156-157; A. Alt, ‘Augusta Libanensis’, ZDPVl 1, 1955, 173; Hartal (n. 25), 433-434 with reservations. Compare Μ. Sartre, Trois études sur l'Arabie romaine et byzantine (Brux- elles, 1982), 66-69; he firmly rejects the connection in Sartre (n. 1) (from 1992), 130.

29 G. Schumacher, The Jaulan (London, 1888), 11, 13. 30 F. Huguet, ‘Aperçu géomorpholologique sur les paysages volcaniques du Haüran’, in: J.-M.

Denzer (ed.), Hauran I, Paris, 1985, 11. See too Ma'oz (n. 10), 525: ‘Tlie Golan can be di- vided into three districts: the fertile plain of southern Golan from the Yarinûk to Nahal Samak and Mt. Peres [a direct continuation of the en-NOqrah plateau in the southern Hafl-

THE CIVIL REFORM OF DIOCLETIAN IN THE SOUTHERN LEVANT114

To sum up, the strip as a human or a geographic unit is a marginal landscape — an empty or sparsely occupied fringe zone, a frontier — with no regular cereal agriculture. It is worth noting how deeply the concept o f ‘end of agriculture = end of civilization’ is rooted in human thought. In Greek myth the borderline is sharp: here ends the dominion o f Demeter and begins the realm o f Pan. Thus, it is quite appropriate for the given land- scape that the cult o f the god Pan is found at Bâniyâs and the HaGran, the two ‘terminals’ o f the strip.31 There is a marked difference between marginal land — frontier — and wasteland. The former is suitable for grazing and, in some places, for intensive agricul- ture, occasionally on a considerable scale. Furthermore, on marginal lands, various physical operations, such as the clearing o f rocks to expose the underlying soil, the use of canals and irrigation, and the adaptation o f suitable plants — such as olive trees or vines — may turn fields that were previously wilderness into fertile areas. We can now better understand why Diocletian’s censitores marked village land only in the strip and not in cultivated regions or in the wilderness. This would suggest that Diocletian’s Tet- rarchic operations in the Haûran-Golan-Hûlah Valley were not aimed at increasing tax revenues (at least not for the first years) but were an effort to reclaim and settle land in marginal and previously unoccupied territories of the frontier. Such a project would be facilitated by the military road, which was later built and called the ‘Strata Diocletiana’, a road leading from the Haüran to Damascus and through Palmyra to the Euphrates.32

In undulating plains with no prominent geographical limits such as rivers or terrestrial crests, provincial borders (or any borders, for that matter) tend to ‘exist’ only vaguely. Fringe zones are the near equivalents of ‘no man’s land’. Mapping such a frontier zone and ascribing a list o f villages to one province and a second to a neighbor constitutes the physical creation o f a border. When using BS, local Tetrarchic governors may have unin- tentionally gained an exact demarcation o f the three provinces’ joint limits. The present BS evidence, it is true, does not allow such a drawing of the borderlines; but future find- ings and research, using additional geographic and early Ottoman administrative data, might help others succeed where we have failed.

The thirty-five BS inscriptions from the strip (except for the stones o f Damascus and Hippos) record nearly 26 place-names (toponyms). They are copied below, arranged according to Fergus Millar’s groupings, i.e. Golan, HQlah Valley, Batanaea (= southern Haüran) and (northern) Haüran. The names are reproduced here as they appear on the

ran]; the central Golan, from Nahal Samak to Nahal Shü'ah — Kafr Nafakh, south of QuneT- tra. which is rocky terrain with an abundance of masils [shallow water courses], mainly suitable for grazing but also for olive growing and with some plots with irrigation by flood- ing; and the northern Golan, from Nahal ShQ'ah — Quneltra to Nahal Sa'ar — a once densely forested plateau with numerous volcanoes and a few springs’. On the ‘frontier’ in Greek thought: Ph. Borgeaud, The Cult o f Pan in Ancient Greece (Chi- cago, 1988); on the cult of Pan in the Haüran see Μ. Dunand, Le musée de Soueïda: Inscriptions et monuments figurés (Paris, 1934), 39, pl. xvii, no. 47 (from Qanawât). Millar (n. 1), 177; D. van Berchem, L'armée de Dioclétien et la réforme constantinienne (Paris, 1952), 3-6; Williams (n. 6), 94-95, fig. 2; Lewin (n. 23, 1990), 141; id n. 23, 2002); Μ. Sartre, ‘Les IGLS et la toponymie du Haurân’, Syria 79, 2002, 217-229.

115ZVI URI Μ ΑΖ

stones, in the genitive case, without breathings or accents (Their possible identifications with present day villages appear in brackets.):33

Paniou (Bàniyâs), Σαρισων κα Βερνικης (Sürman? and QuneTtra?), Αχανων (Kh. Α1- MhfT?), Αγριππινης — Ραδανο[υ] (1Asheshe?), Αριμος κα Ευσωμ (QasrTn and al- Ahmadlyyeh?), Χρησιμιανου (Ghajar?), Γαλανιας, Ραμης, Μιγηραμης, Δηρας κα'ι Κα- παρ[μ]ιγη[ραμης], Μαμσιας κ Βεθ Αχων (Tell al-Wàwîyàt), Δηρας κ Ωσεες, Ωσεας κ Περισης, μητροκωμας Ακραβης κα Ασιχου (‘Aqraba and Umm al-‘Awsej?), Γα[σ]ιμεας κα Ναμαριων (Jasem and Namer), Ορελων ρου — Μαξιμιανπολ[εως] (Jüneineh and Saqâ), Διον[υσια]δος (Süweida), Αθελην[ω]ν (‘Athïl), Νεειλων κα [*Σ]εμε[λε]νων34 (Simlîn?), Μαλα[ας] κα Σαεμεας, (Mleîha35 and Sami'â east of ‘Aqrabà), Οπαεπων κατωτρας (Ghabagheb) κα Ραγηνων κα Καπαρζεθα, [-]ανηλω[ν], [Βαθυ]ρας? (BasTr36).

Two phenomena regarding this list are striking. First, without delving into linguistics, it is obvious that most o f the names, apart from Capar-Zetha and the first component o f Beth-Achon, and Capar-[M]ige[rames] are neither Semitic37 nor Greek. Only four names, Berenike, Agrippine, Maximianopolis (Saqâ) and perhaps Dionysias (if the resto- ration is correct — SüweTdâ) are certainly Greek. These were probably the central, and possibly even the original, settlements. The etymology o f the remaining twenty names is unfortunately beyond the grasp of our present knowledge. The second notable fact about the list is that fifteen out o f twenty-six ancient names on the BS stones do not reappear in other historical records or in modem toponymy. Exceptions are the Haüran sites o f

33 Millar (n. 1), 540-544; see too the additions by Sartre (n. 1); Di Segni (n. 24), 158-187; SEG xlv (1998), 582-4, nos. 2005-10; Hartal (n. 24), 361-2, 431-7; Ben-Efraim (n. 24), 16. Syon and Hartal (n. 24) have a full list on 238-9.

34 Suggested by Sartre (n. Ι), 114 and SEG xlv (1998), 582, no. 2005. 35 The identification by Sartre (n. Ι), 118-119 of BS Malafas] with MleThah (Sarqîyyeh, east of

‘Aqrabâ) is not as straightforward as it appears. Since the Arabic name means ‘salty field’ or ‘area’, the name is probably based on physical conditions and does not reflect the ancient name. The similarity is no more than a coincidence.

36 Sartre's identification [(n. 1), 123], however tempting (and accepted by SEG xlv [1998], no. 2010), is based only on the final two letters of the name. It would be irresponsible, in my view, to use the identification as a basis for any conclusions. Nevertheless, BasTr itself pro- duced a BS, albeit without a name (Sartre [n. 1], 125), so it is plausible that Bathyra was on the Tetrarchic project list; see the following note.

Namarion is probably not derived from Semitic namer/nimr (Jer. 13:23) and Akrabe is ’7 probably not derived from ‘Aqrab (2 Chr 10:11). The Semitic form of the name is .Aqrabat/ah. Semitic toponyms called after animals are rare or non-existent‘ \ See e.g. Y. Aharoni, The Land o f the Bible: A Historical Geography (Enlarged and revised ed.; trans, and ed. Α. Rainey) (Philadelphia, 1979), Index; Y. Elitzur, Ancient Place Names in the Holy Land (Jerusalem, 2004), 54-57 and Index. Bathyra, which is perhaps not on the BS list, but is found in the same region, is most likely the heart of the outlaws’ zone, where Herod settled 3000 Edomites and established military colonies (of Babylonian Jews) in order to pacify the locals in ca. 23 BCE, see Josephus, XV, 342-8; XVI, 285; XVII, 23-31; BJ I, 398-400; B. Isaac, ‘Bandits in Judaea and Arabia’, The Near East Under Ro- man Rule: Selected Papers (Leiden, 1998), 128-9, 152-8; Z.IJ. Ma‘oz, The Golan Heights in Antiquity: A Study in Historical Geography (Qazrin, 1986), 89 (Hebrew). According to our hypothesis, the name Bathira is a Babylonian personal name.

THE CIVIL REFORM OF DIOCLETIAN IN THE SOUTHERN LEVANT116

‘Aqrabâ, Jasm and Namer, which were recorded in the Syriac Archimandrites’ list (ca. 570 CE);38 Ghabagheb, Baslr, ‘AthTl, Mlelhah, Sami‘a and perhaps Simlm, still exist.39 Why did these names disappear? If I may hazard a guess, perhaps the majority o f these fifteen villages did not survive after Diocletian (or after the fourth and fifth centuries CE). Or — and this is quite likely — some village names may have been put on the set- tlement map and on stone markers in the fields as future projects, projects which in the event never materialized. Such unexecuted or unsuccessful settlement plans can be found everywhere and in every period.

I would suggest, then, that the placement o f Diocletian’s Tetrarchic boundary stones was part of a large-scale operation to turn marginal, unpopulated grazing grounds into intensively cultivated fields around core villages. In other words, there was an attempt to add new settlements in the spaces between and around preexisting, sparsely populated centers. Six BS — with ‘new names’ (mostly not preserved) — were found between al- Harah on the west and SanameTn on the east, and around them, in an area o f about 20 χ 20 km.‘10 In the area o f Paneas, 12 BS were placed in regions to the south and west o f the well-known city. In my view, the fact that the overwhelming majority of BS names did not survive to the sixth century CE or beyond seems to indicate that about two-thirds of

Full list in Syriac: M.Th.-J. Lami, ‘Profession de foi, addressée par les abbés des couvents de la province d’Arabie à Jacques Baradée’, Actes du onzième congrès international des orientalistes Paris 1897 (Paris, 1898), 125-134. See too Z.IJ. Ma‘oz, O n the Geography of the Settlements of the Ghassânids in the HaQran and the Golan’, Studies o f the Tel Hai Aca- demie College, Jerusalem, forthcoming (Hebrew translation and discussion); Th. Noldeke, ‘Zur Topographie und Geschichte des Damascenischen Gebietes und der Haurangegend’, ZDMC 29, 1875, 419-443; Sartre 1982, 88-187; I. Shahid, Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century (Washington D.C., 1995), i. 2, 824-838; ii. 1, 76-104. See Syrie, Répertoire alphabétique des noms de lieux habités, dressés et publié par la Ser- vice Géographique des Forces Françaises du Levant, (3rd ed., Beirut, 1945). The six new locations are, roughly from west to east: ‘Aqrabâ, Namer, SimlTn, ’Inkhel, BasTr and Khabab. The center at SanameTn, ancient Aire, is known for its monumental 191 CE Temple. See H.C. Butler, Publications o f the Princeton University Archaeological Expedi- tion to Syria in 1904-1905 and 1909, Division II, Section Α: Architecture and other Arts, Southern Syria, Part 6, (Leiden, 1916), 315-322; J. Dentzer-Feydy, ‘Décor architectural et développement du Hauran dans l’antiquité (du Ier s. av. J.-C. au VIIe s. ap. J.-C.)’, in: J.-Μ. Dentzer (ed.), Hauran I: Recherches archéologiques sur la Syrie du Sud à l'époque héllenis- lique et romaine, ii (Paris, 1986), 297, pi. XVIa; Hara’s ancient name was Harïth al-Jaülan and it was in fact the capital of the Ghasânids, whose main camp was immediately south of Hara at Jâbiyat al-Jaülan. On the site called Eutimia in the Byzantine period, see Sartre (n. 1), 219-220. The ‘camp Ghasânid’ was mentioned already in 517 CE and became famous because of the decisive Muslim-Byzantine battle that took place nearby; see I. Shahid, The Martyrs o f Najran (Bruxelles, 1971), 63; id. (n. 39), ii. 1, 96-104; W.E. Kaegi, Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests (Cambridge, 1992), 112-146. HarTth is mentioned several times in the ‘Archimandrites Letter’ (above, n. 38), as having a few monasteries. There is, as yet, no textual or archaeological evidence relating to this site for the period before the 6th century CE.

117ZVI URI ΜΑΖ

the Tetrarchic settlement enterprise failed: the new villages either did not survive for long or were never founded in the first place.'11

Before leaving the issue of the BS we may offer an explanation for the few ‘stray’ BS near Damascus and Hippos: these stones may derive from enclaves found in a previously unpopulated (or sparsely settled) fringe or grazing area.

Diocletian and Paneas

Most intriguing is the possible connection of Diocletian to Paneas. We saw above two Jewish stories which seem to preserve an echo o f his sojourn here. In addition, an excep- tional boundary stone stating: λθος / [δι]ορζω[ν] / τ δρια το / Πανου κε / τ ς πλεως...'12 suggests that the emperor may have reestablished the γ ερ of the temple vis-à-vis the town, or, as seems more likely, may have annexed more land to the estate o f the temple.

Be that as it may, it is appropriate to mention here a luxurious palace exposed in the town-center at Bâniyàs which, according to its excavator Vassilius Tzafferis, was built in the second half of the first century CE, presumably by King Agrippa II (54-93 CE).* 42 43 44 In my view, the architectural features point to the days o f Diocletian, and it was probably begun in 290 CE. The ruins o f the palace (ca. 100 χ 100 m) occupy the southwest quad- rant of the town center. The excavators believe that this huge monument consisted o f four wings around a central open court. Nevertheless, the parts o f the structure thus far exposed exhibit no open air central zone. The south wing includes two symmetrical and unusual entrances to the basement of the building. From the outside, the entrances are flanked, on either side, by semicircular towers and they lead, inside, to underground vaulted corridors. The masonry (possibly Phoenician) is superb and unique. Both ele- ments, the towers and the vaulted corridors, are comparable to Diocletian’s palace at Spalato (Split, Croatia).‘*4 The upper storey of the palace, as uncovered so far, consists o f a series o f parallel huge vaulted halls (for storage?), while in the center there are two

The settlement of the Banü-Ghassân (Ghassànids), in the sixth century CE (see previous note), is a parallel of sorts to the BS settlement, since it took place virtually in the same zone (the former with extensions to the north, west, and south). The ‘Letter of the Archiman- dates’ (above, n. 38) lists 80-100 place names, of which 65 have survived to the present day. They extend from Mt. Hermon and Damascus in the north as far south as the River Yarmükh. It is characteristic of the unchanging nature of this terrain and its living conditions that 50 ancient sites from this list (out of the 65 identified ones) are located within the con- fines of the BS ‘strip’. Many of these fifty place names are known from existing or defunct settlements (compared to only six names out of 30 from the BS list above). Apparently the Ghassânid settlement was far more successful than the Tetrarchic one.

42 S. Appelbaum, B. Isaac and Y. Landau, ‘Varia Epigraphica’, SCI 6, 1981/82, 98 [no. 1], 43 V. Tzafferis, ‘Ten Years of Archaeological Research at Banias’, Qadmoniot 31, 1998, 8-12

(Hebrew); id. ‘Banias, the Town-Center’, NEAEHL, v (Jerusalem and New York, 2006 [forthcoming]), s.v.

44 Τ. Marasoviô, Diocletian's Palace (Belgrade, 1967); J. & T. Marasoviô, Diocletian's Palace (Zagreb, 1970); S. McNally, J. Marasoviô and T. Marasoviô (eds.), Diocletian's Palace: American-Yugoslav Joint Excavations (Dubuque, Iowa, 1989); J.J. Wilkes, Diocletian’s Palace, Split: Residence o f a Retired Roman Emperor (Sheffield, 1986, repr. Oxford, 1993), fig. 3-6, 9, pi. 17, 19.

THE CIVIL REFORM OF DIOCLETIAN IN THE SOUTHERN LEVANT1 18

lavishly decorated halls (basilicae) with large apses on their south. These spaces served as aulae — reception and audience rooms — of the palatial complex. In the central ba- silica a section of the stylobate still carries a pedestal in situ. Near it, a hoard of more than 39 bronze coins has come to light, thirty of which were identified. Noteworthy are two coins of Philip, the founder (κτστης) of Paneas. The majority o f the coins, how- ever, were minted under the Severan emperor Elagabalus with the last coin dated to Gordian III — 238-244 CE.45 46 My suggestion for a Tetrarchic date for this palace is based neither on the pottery (on which the excavator relied), nor on the above coins. It is based solely on the architectural character o f Paneas in general and this structure in par- ticular. Imperial Roman buildings from ca. 50 BC to 235 CE everywhere are decorated, as a rule, by sculptured moldings (mostly vegetal) and statues. The palace unearthed at Paneas cannot be the sole exception to this rule. It must, therefore, be dated on art- historical grounds, to some time after Philip ‘the Arab’ (241-244 CE) whose construe- tions in Shahabâ (Philippopolis) in the Hauran already point to a marked decline in the tradition of architectural décor described above.'16 The ‘severe’ art pattern reaches its zenith, within the Roman period, in Tetrarchic constructions. This general rule of Roman architecture can also be observed in other first and second century CE buildings at Paneas.47 48 These arguments, preliminary as they may be, lend weight to my suggestion that the palace at Paneas was part of the emperor’s initiative in Syria-Phoenice in the 290’s CE. It should be recalled that Diocletian built residences at Antioch, Sirmium, Nicomedia and elsewhere.‘18 I suggest that the Jewish Patriarch was summoned to this very palace during Diocletian’s stay at Paneas (above, p. 108). Diocletian’s building project, taken together with the reclamation and settlement of frontier lands, should be seen, perhaps, as an attempt to acculturate the semi-nomadic tribes o f shepherds who still roamed large parts of the area.49

Thus, in addition to the fiscal and military acts carried out across his entire domain, Diocletian’s Tetrarchic civil reforms in the southern Levant were aimed first and fore- most at the development o f land and settlements in fringe zones. (The water reservoirs at Apamea and Emesa should not be overlooked in this context.) Furthermore, the cities of such backward areas were probably developed by adding new edifices, such as the pal- ace at Paneas, to their sanctuaries and administrative buildings. An overall strategy was implemented: a chain of new habitations was planned along the provincial border zones (more than a hundred km. long), and civil architecture was added to the existing city temples of the first and second century CE. While there is reason to suspect that these

Gabi Bichovsky, curator of coins Israel Antiquities Authority, personal communication. 46 K.S. Freyberger, 'Die Bauten und Bildwerke von Philippopolis’, Damaszener Mitteilungen

6, 1992, 293-311, pis. 59-66. 47 Z.L). Ma'oz, ‘Coin and Temple — The Case of Caesarea-Philippi-Paneas’, INJ 13, 1999,

90-102, pis. 13-15; id. ‘Banias’, NEAEHL v, (Jerusalem and New York, 2006 [forthcom- ing]), s.v.

48 Barnes (n. 6), 49. 49 Y. Nevo, Pagans and Herders: A Re-examination o f the Negev Runoff Cultivation System in

the Byzantine and Early Arab Periods (Jerusalem, 1991). See also Z.LI. Ma’oz, Paneon I, Excavations at Caesarea-Philippi-Baniyas 1988-1993, (ΙΑΑ forthcoming), ch. 7 — Hellenis- tic History.

119ZVI URI ΜΑ'ΟΖ ambitious projects did not last for long in terms of the settlement history o f the country as a whole, Diocletian’s vision of the area, in itself, earns our admiration to this very day.

Golan Research Institute/Golan Antiquities Museum

The starting point o f this endeavor is the uneven distribution o f ‘boundary stones’ (λθοι διορζοντες, inscribed stones marking the border between the land o f villages Χ and Y ; bornes cadestrales, bornes parcellaires; henceforth: BS) across the territories of south- em Syria-Phoenice, northern Palaestina and Arabia, 295-297 CE. These boundary stones appear to be concentrated along a roughly southeast-northwest strip extending from the northern foothill o f Mt. HaQran through the northern Hülah Valley. The rationale under- lying this strip, and the reason behind the placement o f these markers in a sort o f a chain along the length and width of the strip are the subject o f this study.

Maurice Sartre’s latest article on the subject ascribed these inscriptions to ‘fiscal re- forms’.1 Sartre’s approach, however, is unsatisfactory, since fiscal reforms cannot be limited to a specific territory. He himself noted the absence o f BS from the southern HaQran as against their relative abundance further north. Consequently, he contended that the BS were connected with the mapping o f specific units for taxation, units such as non-urban autonomic villages and other special places, i.e. sanctuaries and estates.2 David Graf, on the other hand, defined the problem in much clearer terms. Having noted that earlier land divisions (mostly centuriatio for veteran colonies) have been identified in aerial photographs in several places in Phoenicia, Syria, Palaestina and Arabia, he emphasized the ‘strange ... [phenomenon o f the BS] skirting ... the province o f Arabia’.3 In fact, except for very rare and isolated cases, the BS are missing in the bulk of the terri- tories covered by the Roman provinces in the Levant. (Were these territories exempt from fiscal reforms?) It should be emphasized here that the appearance o f Diocletian’s Tetrarchic BS is the exception, not the rule. The presence of BS in one area, in contrast to their absence elsewhere, is a phenomenon that hitherto has not been explained satis- factorily. The explanation I shall offer pertains only to the BS found in southern Syria and northern Israel and does not relate to the nine BS, dated 297 CE, that were found in the limestone massif o f northern Syria4 or to other BS found sporadically across the rest o f the empire.

1 ‘La Syrie a livré depuis longtemps des bornes cadestrales que l’on a placées, ajuste titre, en rapport avec les opérations de bornage rendues nécessaires par les réformes fiscales de la Tétrarchie’, Μ. Sartre, ‘Nouvelles bornes cadestrales du HaQran sous la Tétrarchie’, Ktéma 17, 1992, 112-131 (112); see also, Α. Deléage, La capitation du Bas-Empire, (Paris, 1945; repr. New York, 1975), 152-157; F. Millar, The Roman Near East 31 BC-AD 337 (Cam- bridge, Mass., 1993), 535; contra W. Goffart, Caput and Colonate (Toronto, 1974), 44, 129-130.

2 Sartre (n. 1), 130. 3 D.F. Graf, ‘First Millennium AD: Roman and Byzantine Periods Landscape Archaeology

and Settlement Pattern’, Studies in the History and Archaeology o f Jordan, vii, (Amman, 2001), 475-476; based on Millar (n. 1), 535-544.

4 H. Seyrig, ‘Bornes cadestrales du Gebel Sim'an’, in G. Tchalenko (ed.), Villages antiques de la Syrie du Nord iii (Paris, 1958), 6-10.

Scripta Classica Israelica vol. XXV 2006 pp. 105-119

THE CIVIL REFORM OF DIOCLETIAN IN THE SOUTHERN LEVANT106

Damascus t

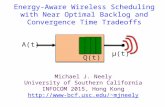

Ο Short version Full version - Lucius and Akakius

Full version - Marius Felix Δ Full version - without name of censilor

Full name in Palaestina Cily

. /P h o e n i c e! ·

* Ρ aneas S o * * o Q I Î l i ' Ο 0 11Γ.ι / 2 4 A

Δ-1 7, w / es-Sanameîn / el-H ara

Trachonitis

/ /

5— Raftd Gaulanitis j l e s t i n a j

Aaaranitis 34 A

© Moshe Hartal Ο 5 10 15 20 ,

Ι Paneas 11 Lehavot Habashan 21 Jermane 3 1 RçleTmeh el-Sharqïyyeh 2 Giser Ghajar 12 Lehavot Habusltn 22 Dârejah 32 Mleltiat el-‘Atash 3 Ma‘ayan Barukh 13 Lehavot Habashan 23 Ghabagheb 33 MleThat SharqTyyeh 4 Tel Tanim 14 Buq‘atS 24 ‘AqrabJI 34 Between SuweTdS and ‘AtTl 5 Shamir 15 QuneTtra 25 Khabab 35 AhmadTyye 6 Shamir 16 QuneTtra 26 BasTr 36 Afiq 7 Shamir 17 QuneTtra 27 Inkhel 37 Afiq 8 Shamir 18 Falim 28 SimlTn 38 Afiq 9 Shamir 19 ‘Eshshe 29 Namer 39 Kefar Haruv 10 LehavotHabashan 20 JisrTn 30 Jflneyneh 40 Kefar Haruv

The Political and Administrative Background

In the course o f the Tetrarchic reforms (including divisions and further segmentation of the provinces: 285/6, 293 CE5), Diocletian became the Augustus of the Eastern empire, which he ruled from Nicomedia in northwestern Asia Minor.6 Apparently Diocletian’s

Diocletian cut the province into fragments: provinciae quoque in frusta concisae (Lactantius DMP vii.4, ed. J.L. Creed [1984], 13). There is no ancient continuous narrative on the reign of Diocletian (284-305 CE). See provi- sionally W. Seston, Dioclétien et la Tétrarchie (Paris, 1946); Μ. Rostovtzef'f, The Social and Economie History o f the Roman Empire (2nd ed. rev. by Ρ.Μ. Fraser) (Oxford, 1957), 502-532 (= D. Kagan (ed.), Problems in Ancient History — The Roman World [New York and London, 1966], ii, 396-413); Α.Η.Μ, Jones, The Later Roman Empire 284-602 (Oxford, 1964), 37-76; i .D. Bames, The New Empire o f Diocletian and Constantine (Cambridge, Mass., 1984); Μ. Grant, The Collapse and Recovery o f the Roman Empire (London, 1999),

107ZVI URI ΜΑ'ΟΖ

political and administrative efforts were aimed not only at gaining a tighter grip over the provinces and their revenues, but also, and perhaps more importantly, were an attempt to assist local populations by concentrating closely on each region or province. Α possible example of such a localized approach is the placement o f boundary stones in the Levant.

Did the emperor ever set foot in the Levant and was he personally involved in the BS project? It is certain that Diocletian visited the Levant in 290 CE. His trip to Syria (in- eluding Antioch, Emesa, Laodicea and Paneas [see below]) and the campaign against the Saraceni will have lasted about two months.7 Several ancient Jewish writings mention Diocletian in conjunction with Apamea, Emesa (Homs), Tyre and Paneas, and these sources — which in my view are based on a historical kernel8 — may very well be re- lated to the 290 CE trip. It should be emphasized, however, that the emperor sojourned in Syria-Phoenice, not in Palaestina.

The essential Jewish texts are as follows:

: ). , ( : , (, ... . . ... )

It is written: He [God] founded it on seas and established it on rivers (Ps. 24:2): Seven seas surround Eretz Israel: the Great Sea ... the sea of ΡΜΥΥ’ [Apamaea] and there will be the sea {viz. lake, reservoir] of HMS [Emesa, modern Homs], DWKLYTYANWS [Diocletian] made rivers flow and made it [viz. the lake of Emesa]. (yKetubot 12:3, 35b)

There is no real reason to doubt this information and this leads us directly to the main issue o f this paper: Diocletian’s preoccupation with land development — in this case, the irrigation of arid zones. Our next bit of Talmudic evidence relates to the economic boost

39-43; S. Williams, Diocletian and the Roman Recovery (London, 1985). The most recent and detailed treatment of all the aspects of Diocletian’s regime known to me is in Hebrew: Moshe Amit, A History o f the Roman Empire (Jerusalem, 2002), 789-824. According to scholars, Diocletian was in the East several times: he has been assigned trips to Persia in 288 and 293 CE. to Egypt, and possibly to Nicomedia (293-303 CE). See Amit (n. 6), 793-797 and B. Isaac, The Limits o f Empire (2nd revised edition; Oxford, 1990), 73 and 278 (who suggests that there was a mutiny in Egypt). Isaac (ibid., 437), places Diocletian at Antioch in the winters of 287/8 and 288/9 CE and situates him there permanently from 299 through 303 CE. I have not been able to find any supporting evidence for Diocletian’s pre- sumed visits to Palestine in 276 and 297-8 CE (D. Sperber, Roman Palestine, 200-400: The Land [Ramat Gan, 1978], 157, n. 44), or in 286 CE (Μ. Αν-Yonah, The Jews Under Roman and Byzantine Rule [Jerusalem, 1984], 127). Despite the disagreements on Diocletian’s movements in the East, all scholars appear to assign him a sojourn in the northern Levant in the spring-summer of 290 CE. See Isaac (ibid.), 73, 437; Millar (n. 1), 177-179; Barnes (n. 6), 51, who note that in 290 CE Diocletian issued rulings from Antioch (May 6th, Frag. Vat. 276m), Emesa (Hôms; May 10th, CJ 9.41.9) and Laodicea (LattaqTyye; May 25th, CJ 6.15.2[28]). See too Pan. Lat. 11(3).5, 4; 7.Γ They suggest that Diocletian was in Syria, possibly fighting against the Saraceni. Barnes (ibid.), puts the fighting in May-June, because Diocletian was already at Sirmium on July 1st. See Α.Μ. Rabello, O n the Relations between Diocletian and the Jews’, JJS 35, 1984, 147- 67; Α. Marmorstein, ‘Dioclétien à la lumière de la littérature rabbinique’, REJ 88, 1932, 19- 43.

THE CIVIL REFORM OF DIOCLETIAN IN THE SOUTHERN LEVANT108

Diocletian was aiming to give the Levant, for we hear of the emperor’s involvement in a trade fair at Tyre.

.[...] [] : ' ,( . ' :

) , ,

R. Simeon b. Yohanan sent [and] asked R. Simeon b. Yozadak: Don’t you check the fair of Tyre, what it is? ... [He] went and found [that] it was written [= inscribed] there: DYKLTY’NWS [Diocletian] the king donated this eight day fair of Tyre for the GD’ [viz. genius] of my brother ’RKLYS [viz. Maximianus]. (yAvoda Zara 1:4, 39d)9

At the fair, goods were exempt from taxation and that surely stimulated business. How- ever, since the fair was dedicated to idolatry (the genius o f Maximianus), Jews were forbidden to attend it.

Two Talmudic texts point to Diocletian’s connection with Paneas:

, , : . : . ). , (' [...], .

DYKLYTY’NWS [Diocletian] oppressed ( ’a'ik) the sons [inhabitants] of PNYYS [Paneas]. They said to him: We are going [away, fleeing]. Α sophist said to him: They will not go [away], and if they will go [away], they will return... (yShev 9:2, 38d).

Paneas belonged to Syria-Phoenice (not Palaestina) and its population has always been overwhelmingly non-Jewish.10 However, in this source we get the first indication o f a possibly close relationship between Diocletian and this city (more below). We also find:

[...] . [...] [...] . ' -) , ].(' [

DYKLWT [Diocletian] ... became king, he went down to PMYYS [Paneas]. He sent let- ters to the Rabbis [saying]: You will appear before me immediately at the end of the Sabbath ... and Rabbi Yudan the Patriarch and Rabbi Samuel BarNahman went down on their way to bathe in the public bath [δημσιον] of Tiberias. An angitris (=’Αργονατης)

J.C. Greenfield, π Aramaic Inscription from the Reign of Diocletian Preserved in the Pal- estinian Talmud’, Atti 11 del Congresso Internazionale di Studi Fenici e Punici II, Roma, 1991, 499; Millar (n. I), 176. For a meeting between Diocletian and a Jew at Tyre, compare yBerachot 3:1, 6a: ‘... When the king Diocletian arrived here, Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba was observed walking over [impure] graves of Tyre to see him’. Jewish leaders apparently went out of their way to meet the ruler; see below for a possible meeting at Paneas. For the lan- guage of the inscription see also S. Lieberman, Studies in Palestinian Talmudic Literature (Jerusalem, 1991), 445-448 (Hebrew); J. Geiger, ‘Titulus Crucis’, SCI, 1996, 203-205.

10 Z.IJ. Ma'oz ‘Banks’, 137-13 in Ε. Stem (ed.), The New Encyclopedia o f Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land (Jerusalem and New York, 1993) (hereafter NEAEHL)\ G. Holscher, ‘Banias’, PRE 36 (1949), col. 594 sqq.

109ZVI URI ΜΑ'ΟΖ

appeared before them... at the end of the Sabbath he took them and carried them [to Dio- cletian at Paneas], (yTer 8:11, 46b-c)u

I contend that this last legend has a historical kernel. Diocletian was in the Levant in 290 CE and travelled as far south as Tyre. Paneas was in the hinterland o f the Phoenician coastal cities and on the main route to Damascus. Our previous source told o f the em- peror’s personal involvement with the taxation of Paneas. It is, therefore, highly likely that during his stay at Paneas, Diocletian summoned the leaders o f the Jewish commu- nity, who were located only about 65 km away, at Tiberias. Our legendary narrative points to the possibility of a meeting between the emperor and the Jewish leadership which took place, in all likelihood, at Paneas in the late spring o f 290 CE. The tale may even hint at a residence o f the emperor in Paneas (below, p. 117).

Diocletian toured the Levant again in 300-302 CE.11 12 As we shall presently see, the boundary stones were set, according to the inscriptions they bear, in the years 295-297 CE. Diocletian was not present in those particular years in the Levant and clearly did not supervise the erection o f the BS personally. However, he could have conceived the pro- ject and ordered the execution of the project himself while he campaigned in Syria- Phoenice some years earlier.13

The Land Reform

Along with the administrative changes came a tighter grip on the economy. It is most evident in the monetary reform and the empire-wide order regarding maximum price tariffs and salaries.14 The emperor could not much influence natural factors beyond his control, such as drought and plagues, other than offering post factum assistance,15 and consequently he devoted his efforts to combating inflation (through the list o f maximum prices), reorganizing the monetary/currency systems and attempting to form an equal basis for agricultural taxation. Lactantius provides a detailed description o f the kind o f

11 The Aramaic text is edited by Y.Z. Eliav, Mituv Teveria 10, 1995, 25 (Hebrew); my English translation is based on that of Yaron Zvi Eliav and David Rokeah. For the miraculous mari- time voyage from Tiberias to Paneas, see Z.IJ. Ma‘oz, ‘Roman War-Ships on Coins — Voyages on the River Styx’, INJ 16, 2007 (forthcoming).

12 Eusebius testified that he first set eyes upon the young Constantine in Caesarea, Palestine: ‘We knew him ourselves as he traveled through the land of Palestine in company with the senior Emperor, at whose right he stood’, (VC I, 19 [ trans. Cameron and Hall, 1999, 77). Millar (n. 1), 179, posits a trip of Diocletian and his entourage (comitates) to Egypt through Palestine between the years 300 and 302 CE on the basis of Eusebius; Isaac (n. 7), 290 ad- duces papyri dated 298 CE which tell of preparations for that royal visit.

13 Since, as we argue below, the BS indicate a land reclamation and settlement project, the emperor’s personal involvement is highly plausible; see below, p. 114.

14 Millar (n. 1), 180-189; Α. Cameron, The Later Roman Empire, 284-430 (London, 1993), 193-194: Edictum de maximis pretiis 301 or 303; H. Blumner (ed.), Der Maximaltarif des Diokletian (Berlin, 1958); S. Lauffer (ed.), Diokletians Preisedikt (Berlin, 1971); E.R. Grazer, Appendix, in: T. Frank, An Economic Survey o f Ancient Rome, v (Baltimore, 1940; repr. Patterson, N.J., 1958), 308-421; Amit (n. 6), 810-812; Cameron (ibid.), 38 notes, among others, that the edict was not effective for long.

15 Sperber (n. 7), 70-99; but see the review of Μ. Goodman, JRS 70, 1980, 35-36.

THE CIVIL REFORM OF DIOCLETIAN IN THE SOUTHERN LEVANT110

census undertaken by Diocletian: ‘Fields were measured out clod by clod, the vines and trees were counted, every kind of animal was registered, and note taken o f every member of the population’.16 Α later legal textbook describes the process (emphasis mine):

...at the time of the assessment there were certain men who were given the authority by the government; they summoned the other mountain dwellers from other regions and bade them assess how much land, by their estimate, produces a modius of wheat or barley in the mountains. In this way they also assessed unsown land, the pasture land for cattle, as to how much tax it should yield to the fisc.17

According to Jones, ‘In the Eastern provinces Diocletian seems to have registered only the rural population, the rusticana plebs, quae extra muros posita capitationem suam detulit, as he puts it in a constitution addressed to the governor o f Syria (in other prov- inces urban population was included)’.18 It is important to emphasize here that the boundary stones operation began in 295 CE, that is, two years before the general empire- wide census of 297 CE and seven years after the initial 287 CE census about which we know next to nothing. It is likely, therefore, that our local BS had no connection, or only a peripheral relation, to the agricultural fiscal reform.

Did the population under Diocletian’s rule face a problem of a severe shortage of available cultivable land? This question is o f utmost importance for our inquiry. The answer, however, is not unequivocal, for we have two seemingly opposite testimonies. Lactantius relates:

The number of recipients began to exceed the number of contributors by so much that, with farmers’ resources exhausted by the enormous size of the requisitions, fields became deserted and cultivable land turned into forest. (DMP vii, 3; trans. J.L. Creed [1984], 13)

In the course o f the mid-third century, cultivable land changed its status from that o f free property owned by small village farmers to that concentrated in the hands o f rich land- lords. The phenomenon engulfed all the Mediterranean provinces, including Palaestina.19 Therefore, our next bit of contemporary evidence does not necessarily contradict Lactan- tius, who may have described an ongoing process rather than the final status of land in the provinces. According to the Babylonian Talmud, new generations o f farmers looked in vain for fields to till, to the extent that a contemporary Palestinian sage, R. ’EYazar b. Pedat (of Tiberias, floruit circa 250-279 CE), states the following:

( ], [ ' ’ , : )

16 DMP xxiii. 2 (trans. i.L. Creed [1984]), 37. Even though the description pertains to Galerius’ census of 307, most interpreters believe it also holds true for Diocletian’s general census of 297, and could perhaps apply to the first census of 287 CE as well. See Amit (n. 6), 806-807; Deléage (n. 1), 148-162.

17 Syro-Roman Law Book exxi FIRA II., 796 (trans. Α. Cameron [1993]), 36. 18 Jones (n. 6), 63. 19 Α.Η.Μ. Jones, ‘Census Records of the Later Roman Empire’, JRS 43, 1953, 49-64; Sperber

(1978), 150-152, 187-203.

I l lZVI URI Μ Α Ζ Fields are only given to the ba'alei Zero'ot, as it is written: ‘The man of the arm (ve ’ish zero'a i.e. a mighty man) to him the earth [and the exalted one shall dwell in it]’ (Job 22:8). (bSanhedrin, 58b)20

Daniel Sperber noted that ‘it is surely significant that in the whole of Diocletian’s very lengthy and detailed Edict o f Maximum Prices, which was intended to reduce inflated costs, the prices of land are never mentioned’.21 Land may not have been a market prob- lem by the time o f the edict of 301 CE, but could have been an issue for the previous generation. Be that as it may, Diocletian’s keen interest in land issues is demonstrated by his introduction o f a new land unit for taxation purposes, the iugum, and also by his leg- islation dealing with the problem of land being sold (or bought) too cheaply.·22

Building Activity

Rulers have always known that building operations are not only everlasting memorials to their glory, but also a powerful stimulus to a lagging economy. Hence Diocletian, appar- ently a devoted student of the several great Roman emperors who preceded him, did not neglect this area of activity. Lactantius tells us o f his passion for building the new capital city Nicomedia (DMP vii, 8-10; trans. J.L. Creed [1984], 13) and it is highly unlikely that the capital was the only city built by the emperor.

We have already adduced sources relating to the construction of reservoirs at Apamea and Emesa, the regulation of the trade-fair at Tyre and perhaps the building of a palace at Bâniyâs/Paneas (to which we shall return). At this juncture, it is important to note Diocletian’s emphasis on the empire’s outskirts. In addition to his fortifications along the Persian frontier, it is clear, as five inscriptions (to date) reveal, that he was in- volved in the construction of legionary camps and roads along the desert frontier in the provinces of Arabia and Syria. According to the not too reliable 6* century CE historian John Malalas, Diocletian ‘built a chain of forts along the frontier from Egypt to Persia, and posted limitanei in them, and appointed commanders to guard each province with forts and numerous troops’. Furthermore, special efforts were made to integrate the semi- nomadic Arab tribes into the defense of the eastern frontier.23

If we bear this in mind, as well as Lactantius’ testimony on Diocletian’s passion for building, it is likely that the emperor was also personally involved in the details of build- ing and settlement activities that took place in the Near East. Diocletian may well have had a say in the positioning of the boundary stones, even though our sources reveal that

20 Translated by Sperber (n. 7), 128; see in general his chap. IV. 21 Sperber (n. 7), 158. 22 CJ 4.44.2; 4.44.8; Goffart (n. 1), 3 Iff.; Sperber (n. 7), 159; Frank (n. 15), Appendix to Vol.

5; Lauffer (n. 15). 23 Malalas Chronicon, 12, 38; trans, by Williams (n. 6), 95; Isaac (n. 7), 164-167; G.W. Bow-

ersock, Roman Arabia (Cambridge, Mass., 1983), 106-109, 138-147; Α. Lewin, ‘Dali’ Euphrate al Mar Rosso: Diocleziano, 1’esercito e i confini tardo-antichi’, Athenaeum 78, 1990, 141; id. ‘Diocletian: Politics and limites in the Near East’, in: Ρ. Freeman et al. (eds.), Limes XVIII: Proceedings of the ΧΙ ΙΙ International Congress o f Roman Frontier Studies held in Amman, Jordan (September 2000) (BAR International Series 1084 [I]) (Oxford, 2002), 91-101; I. Shahid, Rome and the Arabs: A Prolegomenon to the Study o f Byzantium and the Arabs (Washington D.C., 1984).

THE CIVIL REFORM OF DIOCLETIAN IN THE SOUTHERN LEVANT112

the BS operation was carried out between his visits, five years after he left Syria and two years before his empire-wide census.

The Number of Boundary Stones and their Locations: The Frontier

In comparison to Ariel Lewin’s 2002 assessment of Diocletian’s military operations on the eastern imperial frontier from the Euphrates to the Red Sea, the scope o f the BS is severely limited. There are only 41 Boundary Stones known to date in the entire 6700 sq. km research area.24

Several BS bear inscriptions that date them not only to the Tetrarchic era, indicated by the names of the rulers, but also specifically to 295-297 CE. The fullest inscription formula appears many times and can be exemplified by the stone from Gisr Ghajar, north of the Hülah Valley:

Διοκλητιανς κα'ι Μαξιμιανς Σεβ(αστοι) κα Κωνστντιος και Μαξιμιανς Κσαρες λθον διορζοντα γρος ποικου Χρησιμιανο στηριχθνε κλευσαν φροντιδι λιου Στατοτου το διασημ(οττου)

Diocletian and Maximian, Augusti, and Constantius and Maximian, Caesars, ordered a stone to be fixed marking the boundary of the fields of the colony Chresimianus, under the management of the most honourable Aelius Statutus.

Except for six instances, all the BS form a sort o f an interwoven complex chain; in other words, they are distributed (Map l)25 not on a single straight line, but in clusters on a curve. The six deviations include three BS that were found immediately east and south of Damascus, and the other three immediately east and south o f Hippos. The remaining BS were discovered within an elongated, roughly straight strip 112 km long and only 15 km across. It begins in the SE at Junemeh (5 km east of Saqâ-Maximianopolis, at the north- em foot o f Mt. Haflran/Jabal ad-Druze) and terminates in the NW near the Bridge over the Hasbani River at Gisr Ghajar (in accordance with the recently found inscription at Tel Tanim-Tell el-Wâwïyât, just east of Kiryat Shmonah at the eastern foot o f the Moun- tains of Galilee).26 The strip is approximately 15 km across, for example between Namer and Ghabagheb in the northern Haüran, or between Buq‘ata in the northern Golan27 and the group on the east edge o f the Hülah Valley. Thus, the entire territory under consid- eration has an area of ca. 1700 sq. km. By comparison, the Haüran, as a hypothetical

The fullest list is in Y. Ben-Efraim, The Boundary between the Provinces o f Palaestina and Phoenicia in the Second and Third Centuries in the Central Golan Heights (ΜΑ thesis, Bar- Ilan University, 2003), 12, 16, Map 3 (Hebrew). See too D. Syon and Μ. Hartal New Tetrarchic Boundary-Stone from the Northern Hula Valley’, SCI 22, 2003, 238-239, Table 1 ; L. Di Segni, Dated Greek Inscriptions from Palestine from the Roman and Byzantine Pe- riods (Ph.D. Thesis, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1977), 43-47, 148, 158-173, 184-187; Μ. Hartal, The Land o f the Ituraeans: Archaeology and History o f Northern Golan in the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine Periods (Qazrin, 2005), 361-362, Map 19 (Hebrew); Thirty-seven BS were already listed by Millar (n. 1), 540-544.

25 Courtesy of Moshe Hartal. 26 Syon and Hartal (n. 24). 27 R.C. Gregg and D. Urman, Jews, Pagans and Christians in the Golan Heights (Atlanta,

1996), 285-286, no. 240.

113ΖVI URI Μ ΑΖ

rectangle cut diagonally by our strip, comprises ca. 6700 sq. km. (77 km from Damascus to Dar‘à [Edre‘1] and 87 km across, from Junelneh, at the northern foothill o f Mt. Hafl- ran, to the Jordan River).

The BS strip is closely related to the provincial borders o f Arabia and Palaestina in the south and Syria-Phoenice in the north. The strip either includes the provincial border (mainly in the Hauran sector), or is tangential to it (in the Golan-Hülah Valley sector). While the exact borderline is not known, the BS are divided, according to the names o f their censitores, between the Roman provinces in the area as follows: 23 in Syria- Phoenice, 12 in Arabia and 6 in Palaestina. Although this difference in number may, at first glance, appear to be simply an accident of recovery, there may well be a connection between the BS distribution and the frontier.28 The BS strip was not meant to demarcate the border between the provinces on the ground. Their texts specifically state that their function is to separate the lands of two villages (with several exceptional cases dealing with sanctuary or estate properties). Nevertheless, the proximity o f these stones to the suggested borderline (for we lack the data to delineate it on a map) appears not to have been accidental.

The key to begin unlocking the ‘secrets’ of the strip is its environmental character — an unpopulated, or sparsely occupied, fringe zone. In 1886 Gottlieb Schumacher wrote:

‘According to the nature of the soil, the Jaulan may be divided into two districts: (1) stony in the northern and middle part, (2) smooth in the south and more cultivable part. ...Stony Jaulan (esh-Sharah, el-Quneitrah and the upper part of ez-Zawiyeh esh-Shurkiyeh) is an altogether rough and wild country [emphasis mine], covered with masses of lava which are poured out from countless volcanoes and spread in every direction. Although of little use agriculturally, it is the more valuable for pasturage... Wherever between the hard solid basaltic blocks there is a spot of earth, or an open rift visible, the most luxurious grass springs up both in winter and spring time, and affords the richest green fodder for the cat- tie of the Bedawin’.29 30

A hundred years later Francis Hugeut wrote: