Late Eocene Asian Climate Seasonality inferred from 18 O of...

Transcript of Late Eocene Asian Climate Seasonality inferred from 18 O of...

Late Eocene Asian Climate Seasonality inferred from δ18O of Tarim Basin Oyster – L. Bougeois

Late Eocene Asian Climate Seasonality inferred from Late Eocene Asian Climate Seasonality inferred from δδ1818O of TarimO of Tarim Basin Oyster Shell (Basin Oyster Shell (Sokolowia buhsii Sokolowia buhsii (Grewingk))(Grewingk))

Laurie BougeoisM1 PSP – UCBL – ENS Lyon

Abstract. The Asian climate is characterized by a strong duality between monsoondominant climate in southeastern Asia and arid climate in central Asia. Based on climate modelling, this pattern has been explained by two main driving mechanisms associated to the IndoAsia collision: uplift of Tibetan Plateau and/or retreat of an epicontinental sea formerly covering Asia. However, climate proxies are lacking to test these hypotheses and understand how and when this climate pattern was established. Here, we reconstruct the climate seasonality from the study of a fossil oyster Sokolowia buhsii (Grewingk) recovered from ~36 Ma marine strata, in the southwestern Tarim Basin. Temperature variations are estimated from oxygen isotopic (δ18O) variations along a perpendicular transect through growth lines of foliated calcite accumulated in the ligamental area during the oyster life. At this time, 93 samples have been collected every 120 µm through ~20 yearlines using a MicromillTM and we are still waiting for mass spectrometer results. We will test if the calcite has a primary signal by studying the correlation between the δ18O, the δ13C and the thickness of growth lines. If so, we will obtain a rare Late Eocene record of seasonal to decadal variability. This would allow testing climate models at the regional scale but also at the global scale during the key cooling period leading to the EoceneOligocene transition at 34 Ma. If successful, the methods developed in this pilot study can be used to extend the climate record in time and space. Further isotopic analysis may yield absolute paleotemperature as well as information on the open sea connection.

Keywords: Seasonality, Oyster Shell, δ18O, Paratethys Sea, Tarim Basin, Eocene

May 11th – July 11th 2009Supervised by Guillaume DupontNivet and GertJan Reichart, Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University

1. INTRODUCTION

Dramatic tectonic and climatic events with primary global and regional repercussions occurred in Asia during the Paleogene period (6524 Ma). However, the Asian Paleogene paleoenvironmental record is still poorly documented. The most outstanding event is the onset of the collision between the India plate and the Eurasian continent around 55 Ma ago. A poorly documented, yet first order paleoenvironmental constraint associated with this collision, is the retreat of an epicontinental sea (the Paratethys) that extended from Europe to Western Asia (Jin et al. 2003, Popov et al. 2004). Our study focuses on the causes and consequences of the sea retreat out of its westernmost extension in the Tarim bay. We analyse the biostratigraphic record from Late Cretaceous to Oligocene Marine sediments for which regional correlations show that the sea in the Tarim Bay was connected with the Tadjik Fergana basin and the Alai basin (Bosboom, 2008).

The sea retreat out of the Tarim Bay is clearly marked in the sedimentary record by a gradual transition from marine (green limestones) to continental conditions (red beds). The age of this marine to continental transition is estimated to have occurred within Eocene to Oligocene times. However, precise dating is the focus of ongoing work (Bosboom, 2008). One of particular interest is that the Tarim regression

may be related to global climate deterioration at the EoceneOligocene transition (EOT). The EOT is characterized by the onset and extension of ice sheets over Antarctica and possibly to global cooling (see DupontNivet et al. (2007) and references therein). Two main mechanisms have been proposed for the EOT. First, the opening of the Drake seaway between Antartica and South America, which may have initialised the Antarctic Circumpolar Current allowing the growth of the Antarctic ice sheets (Kennett, 1997). Alternatively, the Paleogene decrease in atmospheric CO2 levels reaching threshold conditions at the EOT may be responsible for the formation of the Antarctic ice sheet (see de Conto et al. (2003) and references therein). The cause of Paleogene CO2 lowering is the current focus important research. One of the hypotheses is that the weathering of Himalayan range and Tibetan Plateau, trapped atmospheric CO2 that was ultimately buried in sediment (Raymo et al., 1988). In any case, the sea retreat out of the Tarim Bay could be the consequence of a decrease of sea level or by the deformation associated to the uplift of Tibetan Plateau. On the one hand, the sea retreat could have been enhanced by tectonism associated to Tibetan uplift (i.e. uplift of Altun Shan and Kunlun Shan to the South of the Tarim Basin, and the detachment of the Pamir to the West of the Tarim Basin). On the other hand, the sea retreat may be partly or fully attributed to an eustatic drop, in particular the large 60 meter sea level lowering associated to the large

1

Late Eocene Asian Climate Seasonality inferred from δ18O of Tarim Basin Oyster – L. Bougeois

icesheet formation at the EoceneOligocene transition (Katz et al., 2008)

Regionally, the climate change of Asia during the IndoAsia collision is thought to be marked by a dramatic aridification of the continental interiors and monsoonal intensification in the continent margins (Ramstein et al., 1997). Paleoenvironmental studies document a change from a temperate climate to a monsoondominant climate in Southeastern of Asia combined with an aridification in Central Asia as early as EoceneOligocene times (Sun and Wang, 2005). However the age and cause of these major environmental changes are still controversial (mostly because Paleogene paleoenvironmental records are still rare and poorly dated) and the mechanisms responsible for the observed changes are still unconstrained. Global climate model experiments show that the Tarim Basin aridification may equally be the consequence of uplift of Tibetan Plateau, or retreat of the Asian epicontinental sea (Ramstein et al. 1997, Zang et al. 2007). On the one hand, the retreat of Paratethys may have increased the aridification North of Tibetan Plateau, in the Tarim Basin, because the sea played a bufferrole decreasing the difference of temperatures. On the other hand, Tibetan uplift has the combined effect of (1) increasing the Foehn and orogenic barrier effects, bringing warm and dry air mass northward into the Tarim area, and (2) increasing seasonality with colder winters and wetter summers due to alteration of global circulation of jet streams and seasonal shifting of the Intertropical Climate Zone (see Meehl, (1992) and references therein).

In our study, we are interested to document and quantify these climate changes and, particularly, to estimate the seasonality associated to the installation of the duality arid/monsoondominant climate between Southeastern and Central Asia. In 2007, G. DupontNivet and R. Bosboom visited the West Kunlun Shan, in southwestern Tarim Basin. They observed that the change between marine environment and continental environment occurred during late Eocene to Early Oligocene time (Boosbom, 2008). Furthermore, they sampled many previously described (Xiu, 1997) bivalve shells. One of which, a big oyster shell was chosen for this study because the growth of this oyster is well apparent and expressed by numerous growth lines. The oyster is analogous to present day species, like Cassostrea gigas with similar growth lines recorded annually (Lartaud, 2007). The aim of this internship is to analyse stable isotope variations along a perpendicular transect of these growth lines in order to establish climate variations at annual and decadal scales. This information will be used to infer the late Eocene Asian climate seasonality in order to understand the dominant climate system in the region at that time. This is a preliminary pilot study to establish the applicability of the method on the Paleogene fossil bivalves of the Tarim Bay; a method that could be applied to estimate

changes in climate by comparing several oysters from different beds through time.

2. GEOLOGICAL SETTING

2.1. Geological backgroundOur study area is located in the southwestern part of

Tarim Basin, in the West Kunlun Shan range, in the northwestern part of the Tibetan Plateau (Figure 1a). The Tarim Basin is the largest continental Chinese basin and one of the largest endorheic basins in the world. It is 1,500 km from West to East and expands over an area of over 500,000 km². This basin forms a resistant crustal block and fairly undistorted albeit being subjected to continuous shortening since the IndoAsia collision. Today the Tarim Basin is overthrusted by the Tian Shan in the North, the Pamir in the West and the Kunlun Shan in the South. The major sinistral strikelip Altyn Tagh Fault (ATF) forms the southern margin of the Tarim Basin. Ritts et al. (2008) propose that the uplift of Tarim Basin began between 15 and 16 Ma with shortening on the ATF.

The Kunlun Shan is a fold and thrust mountains range which expands of 3,000 km and with an average elevation of 5,000 m. The Kunlun Shan are separated in two parts by the ATF: West Kunlun, in the southwestern Tarim Basin and East Kunlun, in the southeastern Tarim Basin.

From Permian to late Cretaceous time the environment of the Tarim region was mainly terrestrial (Bosboom, 2008). In late Cretaceous time, the sea invaded the southwestern Tarim region with a large transgression (Jin et al., 2008). The sea reaches a maximum of transgression possibly in late Eocene time during the initial growth of North Tibetan Plateau (Bosboom, 2008). Then, from early Oligocene to Holocene times, the main environment remained terrestrial. However, Ritts et al. (2008) indicate that 15 to 16 Ma ago, there was a marine transgression over the southern and the western Tarim Basin along the North of the ATF. This would be the combined result of the Langhian sea level high and a flexural depression during mountains growth of the Altun Shan and West Kunlun Shan recorded by the rapid thermochronologic cooling of the Altun Shan coeval with Late Miocene deposition of very thick molasses successions deposits (Jin et al., 2003).

2.2 The Kezi SectionThe studied bivalve from this study is from the Kezi

Section (Figure 1a) located along the Kezi River and its tributary streams (38°26'N, 76°24'E (Bosboom, 2008)). Its measured thickness is 224.8m and the strata are dipping homogeneously 30° to the North. The strata bearing the oyster have been biostratigraphy dated to the Early Priabonian (~36 Ma), based on dinoflagellate identification (Sander and Brinkhus, personal communication). The strata belongs to the Bashibulake

2

Late Eocene Asian Climate Seasonality inferred from δ18O of Tarim Basin Oyster – L. Bougeois

Formation (nomenclature according to Yin et al., 2002) that is composed of two parts: (1) greyishgreen mudstones, siltstones and shell beds in the lower part (mainly marine deposits), and (2) purplishred mudstones, siltstones and sandstones in the upper part (mainly continental deposits). The oyster studied here was found at the 60.6 meter level (Figure 1b) within the first unit of the Kezi section (125 to 40 meter level) composed of massive calcareous green sandstones and limestones with shell and oyster beds, which are cyclically interbedded with green marls. The separation between marine deposits and continental deposits is observed at the 20 meter level, after which we can see mainly red laminated mud interbedded with limestones (third part) or with increasingly dominant presence of siltstones (fourth part). The entire lithostratigraphy of the Kezi Section is interpreted as a progradation of a riverdominated delta system within an overall regressive sequence (Bosboom, 2008).

3. MATERIAL AND METHODS

3.1. Determination of the oyster genus and its ecological environment

The genus determination was challenging due to the very small community of researcher acquainted with this particular oyster. In fact most relevant studies are written in Chinese using their own nomenclature. According to Xiu (1997 and personal communication) our oyster could belong to Sokolowia buhsii (Grewingk) species (Figure 2a). It lived in the subtidal zone to shallow sea area. We have a problem because S. buhsii is assigned to the Wulagen Formation, which is just bellow the Bashibulake Formation. To explain this, we propose three possibilities: (1) we are actually in the Wulagen Formation and we have to review our stratigraphy, (2) S. buhsii still lived during deposition of the Bashibulake formation, (3) our oyster doesn't belong to S. buhsii (Grewingk) species. In any case, this does not affect the age of the oyster defined by dinoflagellates found in the same strata.

To clarify that point, we plan further collaboration with Chinese experts combined by further field investigations. This will allow us to ameliorate the knowledge of the environment and then the depth of seawater. The latter is important because, according to the depth, the δ18O could be very different. By instance, Pycnodontes live in more than 50 meter depth and record a δ18O, which is lower by 1‰ than the δ18O of sea surface at the same time (Lartaud, 2007).

3.2. Shell analysis and samplingStudies of living specimens show that the isotopic

composition of oyster shells is in equilibrium with the water sea (Lartaud, 2007). Thus the variations of δ18O of oyster shells provide an excellent proxy for the variations of seawater temperature and chemistry.

Furthermore, the oyster shell is built by episodic stacking or successive calcite layers in two directions: towards the top and towards the back (Figure 2b). As a result, a section of the oyster was cut perpendicular to the growth line (Figure 2a) to provide a cross section on which to analyse growth lines. This revealed clearly apparent growth lines expressed by cyclical black and white lines on the surface of the cross section, in particular after polishing. Thus, the sample provides a continuous record along the oyster life estimated be of several decades (~25 years). Finally, the important thickness of this oyster shell (~4 cm) allows a high resolution record.

According to Gallstoff (1964) and Carter (1980), oyster shells are constituted by four microstructures: prismatic, foliated and chalky calcites and aragonite. Oyster shells are usually almost exclusively constituted of calcite and just few parts contain aragonite. Foliated and chalky calcite are the main microstructures of oyster shell. The chalky microstructure, with wide pores, is generally associated to rapid growth but it is more vulnerable and can be subjected to reactions of dissolution/recrystallisation. Conversely the foliated calcite is formed of thin strips and is very resistant. As a result, I have avoided chalky calcite in my study in order to obtain a primary record. I focused on the ligamental area, which is made up of mainly foliated calcite and so, well preserved. Furthermore, this part of oyster shell shows very regular growth lines and thus seems to be the best target for the sampling. This part was scanned to precisely map the observed growth lines. I did the sampling along a transect perpendicular to the growth lines in this area (Figure 2c).

To study stable isotopes, samples were extracted from the Oyster using the MicromillTM manufactured by New WaveTM. Thanks to the MicromillTM (Charlier et al., 2006) I could drill precisely located microsamples of 50 µg of calcite. To test and calibrate the MicromillTM, I first drilled a continuous trench perpendicularly to the growth direction in the middle portion of the shell (the thickest area). Then I drilled just spots along a perpendiculary transect of growth lines in the ligamental area. However, this way did now yield enough calcite required for an analysis with the massspectrometer. To obtain more material, I decided to drill trenches along growth lines. Each drilled line precisely follows the growth lines of the shell, where the calcite composition is the same because it was built at the same time. Thus, 93 drilled lines separated by 120 µm have been sampled (Figure 2c). After each drilling, a drop of MilliQ water was poured on the oyster to collect the calcite powder using a micropipette. Then the samples were heated overnight in an oven at 60°C to evaporate the MilliQ water and just the remaining calcite was collected.

3

Late Eocene Asian Climate Seasonality inferred from δ18O of Tarim Basin Oyster – L. Bougeois

3.3. Stable Isotopes analysisThe samples were then analysed using the mass

spectrometer KielIII device coupled to a Finnigan MAT253

The δ18O of calcite and aragonite differ for a given temperature. But, as previously noted, according to Lartaud (2007) almost all the shell of oyster is calcite and only the parts of muscle tie are aragonite. Therefore our sampling in the ligamental area provides without doubt a calcite structure of CaCO3.

According to Epstein et al. (1951) then completed by Craig (1965) and Anderson and Arthur (1983), the relation between seawater temperature (T(°C)), δ18Oc

(‰, PDB) of the oyster shell, and the δ18Ow (‰, SMOW) of seawater is:

T(°C) = 16 – 4.14 * (δ18Oc – δ18Ow) + 0.13 * (δ18Oc – δ18Ow)²

The main problem with this equation is the unknown δ18Ow for the paleoseawater (Figure 3). In the Late Eocene, a warm period with little to no ice sheets, an average for open ocean is estimated at δ18Ow = 1‰ (SMOW) (Lartaud, 2007 and references therein). But this estimation is true just for an average and depends largely on the position (latitude) and the sea connection to the open oceans (according to Schmidt (1999) Δδ18Ow

of oceans may reach more than 5‰). This is a problem for the Paratethys, which is an epicontinental sea. In fact, it is not known if there was a connection between the open ocean and the Paratethys, and, if so, what was the flow between these two basins. Furthermore the rate of precipitations in this area nor the elevation of the surrounding montains are known. These two factors affect the δ18Op of precipitations and thus the δ18Ow of Paratethys seawater (Figure 3).

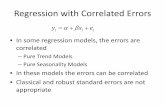

Because the δ18O of Paratethys seawater can not be estimated, the absolute paleotemperature can not be derived. However temperature variations can be estimated by assuming that the sea water oxygen isotope composition remains constant throughout the year. Doing so, the equation can be simplified to:

ΔT(°C) = 4.14 * Δδ18OC

(the last quadratic part of the equation being neglected), such that the temperature variations may be used to trace the seasonality.

4. RESULTS

I do not have results yet because experiments are currently in process. The sampling has been done but samples have not been run through the mass spectrometer yet. I can, however, foresee three possible type of results to be expected: (1) Large temperature variations between summer and winter throughout each year; in this case the Tarim bay most probably already experienced an arid climate typified by hot summers and cold winters. (2) Small temperature variations

throughout each year; in that case, the climate was still probably more temperate. (3) No temperature variation; this would be the consequence of a secondary effect (diagenesis, recrystallisation...) and the record is biased.

5. DISCUSSION AND PROSPECTS

Although I do not have results yet, I foresee their potential implications and further applications depending on which (and if a) primary isotopic record will be extracted from this oyster. First, I will want to compare my results with existing regional climate proxy and model data. For example, Sun and Wang (2005) studied coniferous pollens and propose a more temperate climate than today (semiarid) in Tarim Basin during deposition of the Bashibulake Formation. These results are in agreement with climate models showing aridification associated to the sea retreat (Ramstein et al., 1997, Zang et al. 2007) such that a more temperate climate prevailed just before the sea retreat. My results would enable to estimate if this was actually the case and, moreover, quantify the actual seasonality.

Furthermore, my results may also provide rare northern hemisphere constraints on the seasonality in the period leading up to the EOT. It has been proposed that one of the factor enabling this major climate change to occur has been an increase in climate seasonality (DeConto et al., 2003). However, very few studies provide direct estimates of seasonality in that key period (Ivany et al., 2004). In particular, I will be able to compare my results to recent results from Eldrett et al (2009). They present pollen records from the Arctic Ocean suggesting increased seasonality that are consistent with climate models in the period leading to the EOT. Their results actually provide averaged temperature from comparing the coldest and warmest observed pollen taxa which are then assumed to indicate seasonality. In contrast, my study will provide a more reliable direct measure of seasonality continuous throughout several years.

For the end of my internship I would like to test if there is a fractionation of oxygen associated to the formation of the oyster shell. This has been documented in some cases where δ18O is correlated with the growth rate of the oyster shell. To test possible oxygen fractionation, I will study the correlation between the δ13C and the δ18O because calcite formation strongly fractionates carbon isotopes. I will also compare these results with the thickness of yearly growth lines to see, for example, if faster growth in summer than in winter could bias our data with a fractionation between 16O and 18O. Furthermore I would like to study the 87Sr/86Sr ratio, to estimate the connection between the Paratethys and open oceans.

4

Late Eocene Asian Climate Seasonality inferred from δ18O of Tarim Basin Oyster – L. Bougeois

6. CONCLUSION

This study in progress is the onset of a more important project. The aim is to create and install a protocol using oyster shell and allowing understanding and tracing the seasonality. Others studies used bivalves to trace Paleogene seasonality (Kaandorp et al., 2003 and 2006, Buick and Ivany, 2004, Ivany et al. 2004) but not yet on oyster shell, in the Tarim Basin around the EOT. Other bivalves from the Tarim Basin provide the possibility to extend the study in time from late Cretaceous to Early Oligocene. In addition, the wide occurrence of these marine sediments in other regional basins would allow extending the study in space.

Thus, we could estimates seasonality variations during Paleogene cooling from greenhouse world to icehouse world and understand the installation of the duality between arid and monsoondominant climates in Asia.

7. REFERENCES

Anderson T.F. and Arthur M.A. 1983. Stable isotopes of oxygen and carbon and their application to sedimentology and paleoenvironmental problems. In Stable Isotopes in Sedimentary Geology (ed. M.A. Arthur, T.F. Anderson, I.R. Kaplan, J. Veizer, and L. Land). Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, Short Course, p 1151

Bosboom, R.E. 2008. The retreat of the Paratethys from the Tarim Basin (West China) linked to the EoceneOligocene climate transition and the IndoAsia collision. MSc. Thesis, Faculty of Geosciences Utrecht university, pp. 17.

Buick D.P. and Ivany L.C. 2004. 100 years in the dark : Extreme longevity of Eocene bivalves from Antartica. Geology vol 32. n°10 p. 921924.

Charlier B.L.A., Ginibre C., Morgan D., Nowell G.M., Pearson D.G., Davidson J.P., Ottley C.J. 2006. Methods for the microsampling and highprecision analysis of strontium and rubidium isotopes at single crystal scale for petrological and geochronolical applications. Chemical Geology 232. p 114133

Craig H. 1965. Measurement of oxygen isotope paleotemperatures. In Stable Isotopes in Oceanographic Studies and Paleotemperatures (ed. E. Tongiorgi), Consiglio Nazionale Delle Richerche Laboratorio Di Geologica Nucleare. p 9130

DeConto, R.M., and Pollard, D., 2003, Rapid Cenozoic glaciation of Antarctica induced by declining atmospheric CO2. Nature, v. 421, p. 245249.

DupontNivet, G., Krijgsman, C.G., Abels, H.A., Dai, S., Fang, X., 2007. Tibetan Plateau aridification linked to global cooling at the EoceneOligocene transition, Nature, 445, p 635638

Eldrett J.S., Greenwood D.R., Harding I.C., Huber M. 2009. Increased seasonality through the Eocene to Oligocene transition in northern high latitudes. Nature 459. p 969974

Epstein S., Buchsbaum R., Lowenstam H.A., Urey H.C. 1951 Carbonatewater isotopic temperature scale. Bulletin of the Geological Society of America 64, p 13151326

Ivany L.C., Wilkinson B.H., Lohmann K.C., Johnson E.R., McElroy B.J., Cohen G.J. 2004. Intraannual isotopic variation in Venericardia bivalves: implications for early

Eocene temperature, seasonality, and salinity on the U.S. Gulf Coast. Journal of Sedimentary Research vol. 74 p.719.

Jin X., Wang J., Chen B., Ren L. 2003 Cenozoic depositional sequences in the piedmont of the west Kunlun and their paleogeographic and tectonic implications. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 21. p755–765

Kaandorp R.J.G., Vonhof H.B., Del Busto C. Wesselingh F.R., Ganssen G.M., Marmol A.E., Romero Pittmand L., van Hinte J.E. 2003. Seasonal stable isotope variations of the modern Amazonian freshwater bivalve Anodontites trapesialis. Palaergeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 194. p 339354

Kaandorp R.J.G., Wesselingh F.R., Vonhof H.B.. 2006. Ecological implications from geochemical records of Miocene Western Amazonian bivalves . Journal of South American Earth Sciences 21. p5474

Katz, M.E., Miller, K.G., Wright, J.D., Wade, B.S., Browning, J.V., Cramer, B.S., and Rosenthal, Y., 2008, Stepwise transition from the Eocene greenhouse to the Oligocene icehouse: Nature Geosciences, v. 1, p. 329334.

Kennett J.P., 1977, Cenozoic evolution of Antarctic glaciation, the circumAntarctic oceans and their impact on global paleoceanography: J. Geophys. Res., v. 82, p. 38433859.

Lartaud F. 2007. Les fluctuations haute fréquence de l'environnement au cours des temps géologiques. Mise au point d'un modèle de référence actuel sur l'enregistrement des contrastes saisonniers dans l'Atlantique Nord. Thèse doctorale de l'université Pierre et Marie Curie Paris VI.

Meehl, G.A., 1992, Effect of tropical topography on global climate. Annual review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, v. 20, p. 85112

Popov, S., Rögl, F., Rozanov, A.Y., Steininger, F.F., Shcherba, I.G., and Kovac, M., 2004, LithologicalPaleogeographic maps of Paratethys 10 Maps Late Eocene to Pliocene: Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg, v. 250, p. 142.

Ramstein G., Fluteau F., Besse J., Joussaume S. 1997. Effect of orogeny, plate motion and landsea distribution on Eurasian climate change over the past 30 million years. Nature vol 386 p 788795

Raymo, M.E., Ruddiman, W.F., and Froelich, P.N., 1988, Influence of late Cenozoic mountain building on ocean geochemical cycles. Geology, v. 16, p. 649653.

Ritts B., Yue Y., Graham S., Sobel E., Abbink O.A., Stockli D. 2008. From sea leveal to high elevation in 15 million years: uplift history of the northern Tibetan Plateau margin in the Altun Shan. American Journal of Science vol. 308. 657– 678

Schmidt G.A. 1999 Forward modelling of carbonate proxy data from planktonic foraminifera using oxygen isotope tracers in a global ocean model. Paleoceanography. 14 p 482498

Sun, X., and Wang, P., 2005, How old is the Asian monsoon system? Palaeobotanical records from China: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, v. 222, p. 181222

Xiu L. 1997 Paleogene bivalve communities in the Tarim Basin and their paleoenvironmental implications. Paleowords Number 7. p137157

Yin A., P.E. Rumelhart, R. Butler, E. Cowgill, T.M. Harrison. 2002. Tectonic history of the Altyn Tagh fault system in northern Tibet inferred from Cenozoic sedimentation . GSA bulletin vol. 114. p1257–1295

Zhang, Z., Wang, H., Guo, Z., and Jiang, D., 2007, What triggers the transition of palaeoenvironmental patterns in China, the Tibetan Plateau uplift or the Paratethys Sea retreat?: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, v. 245, p. 317331.

5

Late Eocene Asian Climate Seasonality inferred from δ18O of Tarim Basin Oyster Shell

Annexe 1

Oys

ter

60,

6 m

Mas

sive

cal

care

ous

gree

n sa

ndst

ones

+ lim

esto

nes

Gre

en

mar

ls

Lim

esto

nes

+ gr

een

calc

areo

us s

iltst

ones

Red

mud

ston

es+

silts

tone

s

CONTINENTAL MARINE

Fig

ure

1. (a

) Loc

alis

atio

n of

Kez

i Sec

tion

(K).

(b) S

tratig

raph

y of

the

Kez

i Sec

tion

and

posi

tion

of th

e st

udie

d oy

ster

.

a.

b.K

ezi S

ectio

n

Late Eocene Asian Climate Seasonality inferred from δ18O of Tarim Basin Oyster Shell

Annexe 2

Figure 2. (a) Sokolowia buhsii (Gewingk). (b) Oyster section. (c) Ligamental area with drilled trenches.

b.

4 cm

a.

c.

section

16 cm

Growth directions

Open ocean

δ18Ow = 1‰

Paratethys

δ18Ow = ???

δ18Op= 20‰

δ18Op= 3‰

precipitations?

Mountainselevation?

Connection?

??? ???measured

T(°C) = 16 – 4.14 * (δ18Oc – δ18Ow) => ΔT = 4,14 * Δδ18Oc

Figure 3. Relationship between seawater temperature (T(°C)), δ18Oc of calcite shell (‰, PDB) and δ18Ow of seawater

(‰, SMOW). Problem with the δ18Ow determination due to the lack of knowledge of precipitations, mountain elevation

and connection to open oceans.