I. MOSCHOS, Evidence of Social Re-organization and Reconstruction in Late Helladic IIIC Achaea and...

70

The subject of this paper has two basic themes which, as will be shown later, are very closely linked, interdependent and related (Marazzi 2003, p. 108). This is due to the fact that available space, human activity and the economy in an organized society evolve in a way that is analogous to the society’s character and structure; while space, environment and circumstances sometimes create decisive factors, which impose themselves on society. Before examining Achaea’s place in the long-distance travels and large scale trade, it would be useful to have some knowledge of its social and administrative organization, as much as this can be achieved, by deciphering the archaeological data. The importance of this framework for sea and land trade is clearly reflected in the organization of the trade of the palatial period. Achaea is part of mainland Greece in the North-Western Peloponnese. 1 It faces westward; however, in the Mycenaean period it was at the edge of a basically eastward-looking world. Western Achaea had the privilege of controlling the seaways of the Ionian Sea (Kolonas 1998a, p. 470), whereas Eastern Achaea lies at the junction of land roads from the Eastern Peloponnese and Central Greece. 2 The diverse relations and contacts of each area in Mycenaean times confirm this view. To be more precise, until the LH IIIB period, Aigialeia in the East appeared to be closer to the Argolid, Korinthia and the Eastern Peloponnese, and this is also reflected in the Ships Catalogue of the Iliad. 3 After the decline of the mainland centres, relations and contacts with the northern regions of Phocis and Phthiotis, across the Corinthian gulf, become more intense, 4 in the context 345 APPENDICE IOANNIS MOSCHOS * EVIDENCE OF SOCIAL RE-ORGANIZATION AND RECONSTRUCTION IN LATE HELLADIC IIIC ACHAEA AND MODES OF CONTACTS AND EXCHANGE VIA THE IONIAN AND ADRIATIC SEA * ΣΤ Eforia Proistorikòn kai Klassikòn Archaiotiton, Patra. I want to express my warmest thanks to Michalis Gazis, Georghia Kotsiopoulou and Georghia Merti for translating this text and to Tina McGeorge and Christine Barton for revision. My thanks go also to Reinhard Jung for the discussion and the useful comments on this paper. 1 ANDERSON 1954; V ERMEULE 1960, pp. 1, 19-20; PAPADOPOULOS 1978-79, pp. 21-22; KOLONAS 1998a, pp. 468-469; MOUNTJOY 1999, p. 399; GADOLOU 2000, pp. 44-46; MOSCHOS 2002, pp. 17-20; ID. 2007b, pp. 14-15; RIZIO 2004, pp. 61, 63; KOLONAS forthcoming. 2 MOUNTJOY 1990, pp. 254-256; PAPAZOGLOU-MANIOUDAKI 1998, pp. 156-157; EAD. 1999, p. 279; EDER 2003a, p. 41; EAD. 2007a, pp. 89, 95ff., fig. 8; PETROPOULOS 2007, p. 264. 3 Il. B 198-204 and 569-580; Θ 203; ANDERSON 1954, p. 72; HOPE SIMPSON, LAZENBY 1970, pp. 69, 98; PAPADOPOULOS 1991a, pp. 32, 36; PAPAZOGLOU-MANIOUDAKI 1998, p. 8; MOSCHOS 2002, p. 19, note 10; ID. 2007b, p. 15; EDER 2003b, pp. 304- 306; PETROPOULOS 2002, pp. 143-144; ID. 2007, p. 264. 4 EDER 2003a; PETROPOULOS 2007; some stirrup-jars from Delphi (MOUNTJOY 1990, fig. 25; MÜLLER 1992, p. 470, figs. 13, 3 and 14 left) and Medeon (MOUNTJOY 1990, fig. 25) show connections between Western Achaea and Phocis during the LH IIIC Late period, probably through Aigialeia region. See also infra, note 85. Western Achaea was in a particular way connected to Elateia, in which has been detected the presence of LH IIIC Achaean imported pottery (EDER 2003a, p. 42, fig. 2b; DEGER-

-

Upload

ioannis-moschos -

Category

Documents

-

view

1.185 -

download

13

description

Transcript of I. MOSCHOS, Evidence of Social Re-organization and Reconstruction in Late Helladic IIIC Achaea and...

- 1. APPENDICE Ioannis Moschos * EVIDENCE OF SOCIAL RE-ORGANIZATION AND RECONSTRUCTION IN LATE HELLADIC IIIC ACHAEA AND MODES OF CONTACTS AND EXCHANGE VIA THE IONIAN AND ADRIATIC SEA The subject of this paper has two basic themes which, as will be shown later, are very closelylinked, interdependent and related (Marazzi 2003, p. 108). This is due to the fact that availablespace, human activity and the economy in an organized society evolve in a way that is analogousto the societys character and structure; while space, environment and circumstances sometimescreate decisive factors, which impose themselves on society. Before examining Achaeas place in the long-distance travels and large scale trade, it would beuseful to have some knowledge of its social and administrative organization, as much as this canbe achieved, by deciphering the archaeological data. The importance of this framework for seaand land trade is clearly reflected in the organization of the trade of the palatial period. Achaea is part of mainland Greece in the North-Western Peloponnese.1 It faces westward;however, in the Mycenaean period it was at the edge of a basically eastward-looking world. WesternAchaea had the privilege of controlling the seaways of the Ionian Sea (Kolonas 1998a, p. 470),whereas Eastern Achaea lies at the junction of land roads from the Eastern Peloponnese and CentralGreece.2 The diverse relations and contacts of each area in Mycenaean times confirm this view. To be more precise, until the LH IIIB period, Aigialeia in the East appeared to be closer to theArgolid, Korinthia and the Eastern Peloponnese, and this is also reflected in the Ships Catalogueof the Iliad.3 After the decline of the mainland centres, relations and contacts with the northernregions of Phocis and Phthiotis, across the Corinthian gulf, become more intense,4 in the context * Eforia Proistorikn kai Klassikn Archaiotiton, Patra. I want to express my warmest thanks to Michalis Gazis, Georghia Kotsiopoulou and Georghia Merti for translating thistext and to Tina McGeorge and Christine Barton for revision. My thanks go also to Reinhard Jung for the discussion and theuseful comments on this paper. 1 Anderson 1954; Vermeule 1960, pp. 1, 19-20; Papadopoulos 1978-79, pp. 21-22; Kolonas 1998a, pp. 468-469;Mountjoy 1999, p. 399; Gadolou 2000, pp. 44-46; Moschos 2002, pp. 17-20; Id. 2007b, pp. 14-15; Rizio 2004, pp. 61, 63;Kolonas forthcoming. 2 Mountjoy 1990, pp. 254-256; Papazoglou-Manioudaki 1998, pp. 156-157; Ead. 1999, p. 279; Eder 2003a, p. 41; Ead.2007a, pp. 89, 95ff., fig. 8; Petropoulos 2007, p. 264. 3 Il. B 198-204 and 569-580; 203; Anderson 1954, p. 72; Hope Simpson, Lazenby 1970, pp. 69, 98; Papadopoulos1991a, pp. 32, 36; Papazoglou-Manioudaki 1998, p. 8; Moschos 2002, p. 19, note 10; Id. 2007b, p. 15; Eder 2003b, pp. 304-306; Petropoulos 2002, pp. 143-144; Id. 2007, p. 264. 4 Eder 2003a; Petropoulos 2007; some stirrup-jars from Delphi (Mountjoy 1990, fig. 25; Mller 1992, p. 470, figs.13, 3 and 14 left) and Medeon (Mountjoy 1990, fig. 25) show connections between Western Achaea and Phocis during the LHIIIC Late period, probably through Aigialeia region. See also infra, note 85. Western Achaea was in a particular way connectedto Elateia, in which has been detected the presence of LH IIIC Achaean imported pottery (Eder 2003a, p. 42, fig. 2b; Deger- 345

- 2. Ioannis Moschosof the so-called Western Mainland Koine5 the regions referred to form the eastern part of theKoine. Relations with Western Achaea intensified during the same period as well.6 Western Achaea presented a cohesive and robust cultural identity from the beginning of theMycenaean period7 and, in any case, most obviously after LH IIIA, displaying the features of thewestern coastline of the Peloponnese (Mountjoy 1999, p. 403; Papazoglou-Manioudaki 2003, p.439). During the LH IIIC period the cultural and social features were rapidly transformed andacquired a clearly local character (Mountjoy 1999, p. 404; Moschos 2002; Id. forthcoming), thusmaking of the region the heart of the Western Mainland Koine. This unity extended geographi-cally, with cultural, economical and political consistency, in the region of Patras, of Dyme, ofKalavryta and in the north-western part of Arcadia, from Palaiokastro and along river Alpheiosup to todays North-Western Elis (Rizio 2008, p. 400). Judging from the very few excavationdata that we have at our disposal, Aigialeia is not included. In this large geographical and culturaldistrict of LH IIIC period, which I prefer to call Territory (Moschos 2002, p. 15), there weregeographical areas which formed provinces that were politically viable (Moschos 2002, pp.17-20; Id. 2007a, p. 285ff.).Achaea during the crisis years This development was undoubtedly due to the medium-term and long-term beneficial results ofthe decline of the centralized power of the large Mycenaean centres.8 Among the sites destroyedby fire was Teichos Dymaion,9 the fortified alleged administrative centre of the region. We shouldJalkotzy 2007, p. 133f., figs. 1, 4; 1, 8; cf. Dakoronia 1993, p. 30, fig. 7) pointing out, consequently, the presence of a widetrade net from Elis towards Phocis, Boeotia and Phthiotis already during the LH IIIA-B period; cf. Papadopoulos, Kontorli-Papadopoulou 2006a, p. 711; Bchle 2007; Eder 2007a. Land routes towards the east and south-east of Aigialeia also existedas is clear from several Achaean exported objects at Corinthia and Argolid: for an Achaean stirrup-jar from Argos see Deshayes1966, pl. LX: 8-9; cf. Mountjoy 1990, p. 267ff., fig. 25. Another stirrup-jar and two lekythoi from Tripolis Str. at Argos arelocal imitations of the Achaean Phase 6a style (see infra); see Kanta 1975, pp. 265-266, figs. 11-12. For Achaean pottery inTiryns see Schfer 1971, p. 66 (no. 15), pls. 35, 39; Podzuweit 1983, p. 383, fig. 3:3. For a stirrup-jar of the Achaean Phase6a style at Prophitis Ilias ChT cemetery, see infra, note 88. For a hydria from Korakou, see Rutter 1974, p. 363, fig. 141. It isnoteworthy that the total amount of pottery comes from Western Achaea, so we can assume that in the wider region arrived aland trade net, that started from Elis. 5 Papadopoulos 1978-1979, p. 182; Id. 1991a, p. 32ff.; Id. 1995, with refs.; Id. 1996; Deger-Jalkotzy 1991b, p. 28;Mountjoy 1999, pp. 54-55; Papazoglou-Manioudaki 1998, pp. 102-103; Souyoudzoglou-Haywood 1999, pp. 73-75; Eder2003a, p. 43; Papadopoulos, Kontorli-Papadopoulou 2004; Moschos 2007a, p. 285. For the term Koine see the discussionin Thomatos 2007, pp. 320-322. 6 Petropoulos 2007, p. 264; the newly discovered Naue II sword of type A/Cetona at Nikoleika (ibid., pp. 260, 262, fig. 87)with strongly Italian-related characteristics might be imported from Western Achaea; see Moschos 2002, p. 29, note 69; add alsoPapazoglou-Manioudaki 2003, p. 440, note 90; Petropoulos 2006, p. 41; Deger-Jalkotzy 2006, p. 160. Two LH IIIC Latestirrup-jars at Nikoleika are imported from Voudeni; see Moschos 2007b, p. 43; Petropoulos 2007, p. 258, figs. 12, 56, 59. 7 As would appear from the use of tumuli customs and pottery ware, which are common in Messenia, Elis and Achaea; seeMoschos 2000a. For the Early Mycenaean period in Achaea see Papazoglou-Manioudaki 1998; Ead. 1999; Mountjoy 1999,p. 403; Dietz, Stavropoulou forthcoming. According to Papazoglou-Manioudaki (1998, p. 155), during the Early Mycenaeanperiod, Achaea was placed culturally in North-Eastern Peloponnese. 8 Deger-Jalkotzy 1994, p. 14; Ead. 2006, p. 168; Moschos 2002, p. 32; Eder 2003a, p. 37, note 2 (with refs. for the topic);Ead. 2007b, pp. 42-43; Maran 2006, p. 143. For the crisis caused by the destructions, in general, see Vanschoonwinkel 1991;Drews 1993, p. 22ff.; Mazarakis-Ainian 2000, pp. 35-42. 9 Moschos 2002, p. 20, note 12 (D1), with selected refs.; also add Kolonas 1998b, pp. 287-288, pl. 110; Id. 2006, pp. 219-346

- 3. SOCIAL RE-ORGANIZATION AND RECONSTRUCTIONnot, however, be certain that the fire did destroy the central power in this concrete site, since, sofar, there have been no excavation data to indicate the existence of a palatial building at TeichosDymaion. Indeed, it seems more likely that the fortifications purpose here was partly to protectthe villagers and products of the vast surrounding plateau10 and partly to control the Ionian Seatrade routes. The ruins of the old administrative centre should be sought elsewhere.11 A corroborating fact to this view comes from the new excavation data in the entire region. Afterthe collapse of the palatial administrative system, Achaea witnessed not only the indirect reper-cussions of the unrest, but had first-hand experience of disaster with the fire at Teichos Dymaion,even if the direct target, in the latter case, was not the central power. But Teichos Dymaionis not the only ravaged site in Western Achaea. The on-going excavation at the Mycenaeansettlement of Aghia Kyriaki12 in Patras, to which belonged the extensive cemetery of Voudeni,13reveals a vast fire destruction during this period and a short abandonment of the settlement; sothe plan of the settlement remains consistent after the rebuilding on the ruins. We are not able yetto date this destruction with accuracy because the excavation is in process and the material is stillbeing studied. The settlement of Pagona14 near Patras was destroyed by fire during the LH IIIA or IIIBperiod, according to the preliminary reports. Two pots from the destruction level appear in thesepublications. The first one is a Group B deep bowl in fragments (FS 284) (Stavropoulou-Gatsi1998, p. 519, fig. 9; Ead. 2001, p. 35, note 14), which finds a good parallel in LH IIIB 2 contextat Mycenae, Lion Gate (Mountjoy 1999, p. 150, fig. 39, 297). The other one is a fragmentary FS175 stirrup-jar with FM 18 flowers, a shape which is the earliest known example in Achaea. FS175 stirrup-jar is the most common shape from LH IIIC Middle onwards but it is not present inearlier tomb contexts. It is probably an import and its date can be placed within the transitionalLH IIIB 2/LH IIIC Early phase, which falls partly in Achaean Phase 1 (see infra). Althoughwe have to wait for the final publication, there is some evidence to support a later date for thedestruction at Pagona settlement. As in Aghia Kyriaki, the habitation continued soon after thedestruction (Stavropoulou-Gatsi 2001, p. 35; Stavropoulou-Gatsi, Karageorghis 2003, p. 97). Thesettlement of Chalandritsa15 was not ravaged by fire at the end of LH IIIB or at the beginningof LH IIIC Early, which perhaps indicates that some important settlements managed to escapedestruction. The aforementioned indications in combination with the information we have collected from thecemeteries, and predominantly by the study of the evolution of the local pottery production, lead us,221, figs. 7-12; Kolonas, Gazis 1999, pp. 279-280, figs. 24-27; Rizio 2004, p. 61ff., fig. 5; Id. 2008, p. 402; Moschos 2007b,pp. 14, 25, 27, figs. 19-20. 10As in the case of Gla, see Iakovidis 1992, p. 615; Id. 1995, p. 76; Id. 2001, p. 149ff. 11Moschos 2002, p. 31; see also Dickinson 2006, p. 25. If such a hypothesis is proved to be true by the future excavationsdata, we have to search for other reasons that led to the destruction. 12Moschos 2007b, p. 21; Kolonas forthcoming. For recent excavations on other plots see Stavropoulou-Gatsi 1994, pp.221-222; Stavropoulou-Gatsi et alii 2006, p. 84; Blackman 2000, p. 46. For the character of habitation sites in Achaea seein general Rizio 2008. 13Moschos 2002, pp. 17-18, note 7 (P4), with refs.; also add Kolonas 2006, pp. 217-219, figs. 1-6; Moschos 2007b, pp.19, 21, figs. 1, 3, 5-7, 9-13. 14See Moschos 2002, pp. 17-18, note 7 (P8), with refs.; also add Id. 2007b, p. 21, fig. 14; Stavropoulou-Gatsi,Karageorghis 2003; Stavropoulou-Gatsi et alii 2006, pp. 83-84, fig. 2. 15See Moschos 2002, pp. 17-18, note 7 (P28); also add Id. 2007b, p. 33, figs. 28, 20; Kolonas, Gazis 2006; Kolonas 2006,pp. 225-226, figs. 24-27. 347

- 4. Ioannis Moschoswithout any doubt, to the conclusion that central power in Western Achaea had collapsed regardlessof the destruction of Teichos Dymaion and that the province of Patras was already more power-ful by the time of the Teichos destruction (Moschos 2007b, p. 9; Id. forthcoming). Furthermore,Patras and Dyme already had different courses before the destruction and were not affected in thesame way by that large scale destruction. This diversification continued as the evolution of thetwo provinces was different until the beginning of the LH IIIC Late period. The province of Patrassurpassed Dyme in importance. In my view, there is enough evidence to support the assumptionthat in Western Achaea the social, economic and administrative restructuring had already begunrapidly during the final LH IIIB period and obviously before the Teichos destruction.16 The consequences of the catastrophe in Achaea were not as grave (Moschos 2002, p. 32; Eder2006, p. 557) as those in the large mainland centres and there is some evidence to support this,including the enduring external relations of the region. It is also true that the population was notforced to leave their homes, even if a decline in the number of dead has been documented in the LHIIIB cemeteries, a fact that could be partially attributed to a misdating of the pottery, perhaps becausewe are still unable to distinguish and attribute local elements in the pottery of this period.17 On the contrary, Achaea received a number of refugees, which means that conditions herewere favourable for people having just fled from a disaster. But neither Achaea nor Cephaloniawere flooded with refugees during this period. In Voudeni, the best documented cemetery ofthe region, hardly any new tombs were opened in the LH IIIC, much fewer than during the LHIIIA 2-B period, despite the availability of suitable bedrock (Moschos 2002, pp. 31-32; Kolonasforthcoming). We encounter the same situation in other cemeteries of Achaea of which we haveenough data, such as at Spaliareika, Portes, Mitopolis, Kallithea and Klauss. It is evident that theexisting size of the cemeteries was adequate for the needs of the population using them. In thatrespect, the newcomers must have quickly integrated with the local population of Achaea and hadonly a marginal impact on the new social and administrative re-organization, although its originshave to be sought partly in this group, as we will encounter further on. It is almost certain that refugees had already reached Achaea and Teichos before its destruction(Moschos forthcoming; Kolonas forthcoming). LH IIIB 2 pottery from the Argolid has been foundin coastal sites of Achaea,18 even in the destruction level of Teichos Dymaion.19 In the cemeter-ies of Voudeni and the town of Patras this imported pottery accompanied warriors provided withdaggers. These burials are among the wealthiest of this phase and give us a fragmentary picture ofthe military organization in the region, perhaps even of the social structure, at the time of generaldestructions or even in the very early post-destruction era. 16Moschos 2007b, p. 9; Id. forthcoming. The Palaces economic power and organization were already on the decline beforethe destruction, see Deger-Jalkotzy 1998a, pp. 106-107, with refs. 17During this period a local pottery style is recognized even in Cephalonia, although there is a small number of vases; seeSouyoudzoglou-Haywood 1999, p. 72. 18From newly excavated tombs at Voudeni. From Aigion, see Papadopoulos 1976, pp. 18-19, pls. 50, 58 (BE 675); cf. Id.1978-1979, p. 177; Papazoglou-Manioudaki 1993, p. 211. At Nikoleika (LH IIIB), see Petropoulos 2007, p. 257, fig. 51. 19Three stirrup-jars, see Mastrokostas 1965b, p. 132, pl. 170-; Papadopoulos 1978-1979, fig. 95g; Papazoglou-Manioudaki 1993, p. 211. Several sherds from the ongoing restoration program at this site. A similar vase at Peukes, Elis, witha dumpy shape and narrow base, see Vikatou 2001b, pp. 104-105, fig. 45. Also at Porto Perone, Taranto, see Lo Porto 1963, p.335, fig. 51; Vagnetti, Bettelli 2005, p. 294, II.151. For a parallel at Midea see Demakopoulou 2007a, fig. 20; from Mycenae,see Mountjoy 1999, fig. 37, 285.348

- 5. SOCIAL RE-ORGANIZATION AND RECONSTRUCTION Tab. 1. - Table of the Achaean Phases 1-6, according to local pottery styles and their development. During this particular phase the pottery production acquired evident local features that are easyto distinguish. This early local production composes, in terms of style, a special group, whichchronologically is placed in LH IIIB Final and is unfolded over the so-called transitional LHIIIB/C phase. This stylistic pottery group came to an end during the early part of LH IIIC Earlyand we would say that it comes into completion around the time of the destruction of Teichos.Nevertheless, this is not the fact that contributes to the closure of the specific stylistic group, asit did not have a decisive effect on the situation in Patras province, because the latter had alreadytaken its own development. I strongly believe that this is something that we should look for inthe province of Patras, and for the time being we are ignoring it, assuming that it existed.20 Thisstylistic group of pottery, which has clear time limits and helps us out with the chronologicalarrangement of Achaean pottery, I have named Achaean Phase 121 (tab. 1). In this very early phase the internal influences had two basic characteristics, whichseem to have crucially affected the social and organizational structure, on a political andeconomic level. The first and more obvious characteristic, which has to be seen as a part of thephase, was the continuation of the Argive palatial effect after the end of Argive palaces, in a post-destruction transformation, which very soon fell into decline or acquired local features. ThisArgolid horizon or circle can be seen either as a result of the infiltration of newcomers or refugeesor as protracted local view of decadence. The emerging local elite found the bases of its power inthis horizon,22 contributing to the selected survival and perpetuation of palatial practices, mainlyin matters of prestige,23 marginally in matters of political administration and in no way in matters 20This approach is expected to help the study of the stratigraphic sequence in the settlement of Aghia Kyriaki. 21See Moschos forthcoming. For pottery of this phase at Klauss see Paschalidis, McGeorge in this volume. 22See also the case of Tiryns in Maran 2006, p. 143-144; cf. Deger-Jalkotzy 2006, p. 175; I am under the impression that inAchaea there has not been any attempt to set up an authority analogous to the palatial administration system, either in this phase oreven during the next ones. In this phase we are dealing with a barren neo-elitist demeanour or with the arbitrary use of declinedsymbols, which are not necessarily connected with an effort to establish an old form of authority in the new era. This kind of authorityon a political and administrative level had no more grounds. This demeanour might be analogous to the one of the palatial period,but becomes even more apparent in the post-palatial period. The quick abandonment of that evidence and the subsequent emergenceof new and original features which define the elite in the following phases reveal that this early stage had very little in commonwith the palatial authority, and as transitional should be related to the development and formation of the next phase model. 23The adoption of status symbols is also claimed for Cyprus during the 13th c. while the imports from Argolid had decreasednoticeably due to problems which led to destructions; see Cadogan 2005, p. 320. 349

- 6. Ioannis Moschosof economic organizational structure. It is safe to say that this characteristic lent a conservativeaspect to the form of power of this phase. However, this does not define its overall form, whichseems to be versatile enough and far away from todays boundaries of our knowledge. The second and more persistent characteristic that we can distinguish is the unambiguousparallel local development, which resulted from the lack of the old administrative system andallowed more freedom. This local horizon or circle can be seen either as a time of regenerationand restructuring for all levels of society or as a time when ordinary people found their voice inthe new era. The Minoan pottery found in a warrior burial provided with a dagger in Patras24 and thetwo bronze ladles with Minoan parallels in a wealthy warrior burial with a Dii type dagger atVoudeni25 reflect the fact that voyages from Crete to the Ionian Sea had already been re-organizedafter the collapse and, in my view, even before the Teichos destruction. This is also apparent inthe warrior burial of Voudeni, which was accompanied by pottery with very early local featuresof Phase 1 that can be placed within LH IIIB Final. The presence of an elite in Achaea in this early period is ascertained. To this early classbelonged the two aforementioned warrior burials provided with dagger in Voudeni and in Patras,one burial in Mitopolis26 and probably one more in Klauss,27 both furnished also with daggersof Sandars type D. A warrior burial accompanied with a dagger of an unknown type comesfrom a large chamber tomb at Aghiovlasitika [Papazoglou-Manioudaki 1983, p. 127; for refs.see Moschos 2002, p. 20, note 12 (D7)], in which the pottery dates to the LH IIIB-C period. Twomore daggers of Sandars type E come from near Patras (Sandars 1963, p. 149; Papadopoulos1998a, pp. 20-21, nos. 91, 92, pls. 13, 91; 14, 92) but their dating is not certain (LH II-III) and theyare probably connected with the palatial period, as well as the two type E daggers from Aegeira(Papadopoulos 1998a, pp. 15, no. 66; 23, no. 104; pls. 9, 66; 16, 104; Kontorli-Papadopoulou2003, pp. 38-39, 45, figs. 22, 23; pl. 16, 1-2). The Mitopolis warrior burial was also accompanied by two bronze spearheads of Italian-related typology.28 The imported Italian razor of the type Scoglio del Tonno from Klauss (infra, note158; Paschalidis, McGeorge in this volume), a unique item in Greece, is contemporary to Achaean 24For the Patras warrior at Germanou Str. and its imported stirrup-jars from the Argolid and Crete, see Papazoglou-Manioudaki 1993, pp. 211-212 ( 3945, 3946, 3949), fig. 2-, pls. 23a-b, e-f, 24b; cf. Hallager 2007, p. 192, fig. 3d;Moschos forthcoming. For a preliminary reference to the dagger see also Papazoglou-Manioudaki 1994, p. 200, note 178. 25Voudeni, ChT 21. The warrior burial is accompanied by stirrup-jars imported from the Argolid and other local imitations;see Kolonas forthcoming; Moschos 2007b, figs. 6, 12; Id. forthcoming. A close parallel for this warrior burial comes fromGypsades, Knossos (LM IIIB); see Grammatikaki 1993, p. 448, pl. 139,. For Dii type daggers in the Aegean see Sandars1963, pp. 130-132, 148f.; Driessen, MacDonald 1984, p. 73, fig. 3. For an imported F dagger at Surbo, Lecce, see Macnamara1970, p. 242, fig. 1, 1; von Hase 1990, pp. 93-94, fig. 8, 1, with refs. (note 29). Its date is not so clear (LH IIIB or IIIC Late), seeBranigan 1972. The Surbo sword could bear witness to Cretan-Italian contacts, not necessarily Mycenaean (Hallager 1985,p. 294). Another F type dagger from Dessueri, Sicily, is of later date, see Sandars 1963, p. 151, pls. 25:41, 28:68. A miniatureF type dagger from Pantalica Nord, Sicily, see Sandars 1963, pp. 151-152, pls. 25, 43, 28, 69; Tanasi 2004, fig. 5c. 26It should probably be attributed to LH IIIB Final; see Kolonas, Christakopoulou 1996, p. 236; Christakopoulouforthcoming. Among the pottery is a small piriform jar typical of Phase 1 decorated on the shoulder with solid triangles, whichis again a Minoan feature. 27Papadopoulos 1988b, p. 36, pl. 30; Id. 1998a, pp. 18-19 (no. 80A). According to the kind information of C. Paschalidis,it comes from a pile of pushed aside bones among which there was pottery of LH IIIA 2, LH IIIB and of Achaean Phase 1. Itseems more likely that it belonged to the more recent secondary burial. 28For solid-cast spearheads in Italy see Pacciarelli 2006.350

- 7. SOCIAL RE-ORGANIZATION AND RECONSTRUCTIONPhase 1 as it was found in a burial of this phase. Moreover, at the same phase belongs the Pertosadagger from the destruction level at Teichos Dymaion,29 which also demonstrates the interest inwestern technologies.30 The concern for the acquisition of luxury objects like a Pertosa dagger isknown from the late palatial period or slightly later, in the Argolid region (Mycenae, Tiryns, Nemea),in Messenia, as well as in the Cyclades (Naxos, Melos), although in most cases their date is notclear.31 Of great interest is the Pertosa dagger from Dodone (Papadopoulos 1998a, p. 30, no. 140,pl. 22, 140), which unfortunately we cannot correlate chronologically with the Achaean example.In any case, the pursuit of obtaining a luxury or exotic item could be associated with thepalatial period, and this effort could be an impact from the palatial aspect of power.32 As an analogousremnant could be considered the use of daggers which seem to have accompanied the lower ranksof the palatial power, although there is not enough evidence to support convincingly such anopinion. In addition, the short swords represent perhaps even better than long ones the strength andthe courage of their possessors in hand-to-hand combat, so that we can infer that their presence inthe tombs had also another meaning: they emphasized or stressed the particular characteristics oftheir possessors, a tactic consolidated from the Middle IIIC period onwards with the use of otherobjects or other means. The preference or quest for luxury items or special imitations from a greater area, from Creteto the East up to Italy to the West, appears to have been a very important activity to the elite, asit is reflected on the funerary customs. This activity reveals the size of the contacts as well as thesize of the trade in this early phase. Similar warrior burials with short swords have been discovered in Elis,33 Aetolia34 and 29Mastrokostas 1965a, p. 104, fig. 130; Id. 1965b, pp. 134-135, fig. 177; Papadopoulos 1998a, p. 29, no. 136, pl. 22,136; Papadopoulos, Kontorli-Papadopoulou 2000b, p. 144, pl. 36, 1-2; Borgna, Cssola Guida 2004, pl. VI:1; Oikonomidis2006, p. 146ff., fig. 5, 1; Jung 2006, p. 204, pl. 18, 1. It is not imported from Italy, see Jung, Moschos, Mehofer forthcoming. 30Relations between Italy and Greece during Bronzo Recente/LH IIIB Final or at the transitional LH IIIB 2-LH IIIC Earlyphase arise from the stirrup-jar from Porto Perone (see supra, note 19), probably from the F type dagger from Surbo, Apulia (seesupra, note 25) and pottery from Broglio di Trebisacce, Torre Mordillo and Rocavecchia; see Jung 2005, pp. 479; Id. 2007b. 31For the topic see Matthus 1980b; Harding 1984, pp. 172-173; Schauer 1985; von Hase 1990, p. 95, fig. 9; Bettelli1999, p. 469, fig. 4; Vagnetti 2000, p. 317; Jung 2005, p. 477; Id. in this volume. 32For the symbols of authority in palatial period, see Maran 2006, p. 128, note 8, with refs. Luxury items of palatial times thatcould be associated with Italy and Central Europe are: the gold diadem from the citadel at Pylos (Blegen et alii 1973, p. 16, pl.108d; Bouzek 1985, p. 170); the violin-bow fibulae of LH IIIB 2 date [Kilian 1985, pp. 152 (VA1), 154ff., fig. 2:VA1]; the NaueII type ivory hilt plates and the mould for a winged axe from Mycenae (LH IIIB Middle), as examples of locally made items (Jung2005, pp. 476-477, notes 25, 26, with refs.; Jung 2006, pp. 177-179, pl. 15, 1-2); the Pertosa type dagger from Nemea-Tsoungiza(Papadopoulos 1998a, p. 29, no. 137, pl. 22, 137); probably, some of the other Pertosa type daggers (see supra, note 31); a NaueII type sword from Mycenae (Jung, Moschos, Mehofer forthcoming); the well-known, early examples of Naue II swords of typeA/Cetona in Aegean and Cyprus (Jung 2005, p. 476, pl. 106j, with refs.). In the bibliography is also mentioned an unpublishedbronze hemispherical cup from Mitopolis, Achaea, of LH IIIA-B date (Matthus 1980a, p. 279ff.; Bouzek 1985, p. 52). 33From Kladeos, Trypes, of LH IIIB-C date; in fact it is the same with the Mitopolis dagger (Sandarss type D); seePapadopoulos 1998a, p. 19, no. 80C, pl. 11, 80C. From Miraka, Sandars type E (ibid., pp. 23-24, no. 109, pl. 17, 109); from Pisa-Lakkofolia, Sandars type E (ibid., p. 24, no. 110, pl. 17, 110); from Olympia (Sandars type F?) (Vlling 1994); two from AncientElis of Sandars type F and G (Submycenaean) (see Papadopoulos 1998a, p. 26, no. 123, pl. 20, 123; Eder 1999a, pp. 264-266;Ead. 1999b; Ead. 2001, pp. 77-85, figs. 24-25, pls. 3a:4, 4c:2, 13a,b); a partly preserved dagger is reported from Aghia Triada(Arapogianni 1991, p. 133); recently, four daggers of unknown date and type have been found in the locality of Spilia Arvaniti(Moutzouridis 2007, pp. 97, 99). 34From Lithovouni, Makryneia, Sandars type F (Papadopoulos 1998a, p. 28, no. 131, pl. 21, 131); it dates from theLH IIIB-C, but the presence of two fibulae in the chamber might be an indication for LH IIIC Late date or even Early 351

- 8. Ioannis MoschosCephalonia,35 but the excavation data are not always enough to attest that some of the daggers arecontemporary with the Achaean ones. At the present time, it is very difficult to relate them withthe existence of an analogous early elite in these regions. The presence of these sort of weaponsin warrior burials in Epirus,36 Central Greece37 and in the aforementioned regions, in some casesalready by the LH IIIA, continues until the Submycenaean period.38 In combination with thesimultaneous absence of Naue II type swords from Aetolia and Cephalonia39 and with only twoexamples from Elis40 and one from Akarnania (Stavropoulou-Gatsi 2008), this fact indicates theiruse as highly prestige items of power during the LH IIIC period, through a possible conservativetradition. This tradition goes back to the palatial period and clearly survives from the link thatwas established in Achaea in Phase 1; in addition to everything else, it constitutes the echo ofthe early phase of the Achaean elite. As far as we know from todays evidence, after Phase 1 the Aegean long and short swordsdisappeared from Achaea. It seems that the Naue II type swords replaced this type of weaponryfrom LH IIIC Middle onwards, a fact that does not apply to such a large extent to the rest of North-Western Greece. This means that the warrior burials with Aegean swords or daggers, apart fromAchaea, are not less important than the ones which bear Naue II type swords within Achaea. Inall probability their only difference is the type of weapon that they carried and the effectivenessof each one of them in operating it; and always according to weapon quality.The LH IIIC period and the social organization From the LH IIIB 2 Final to the beginning of the LH IIIC Developed phase, apart from thedestructions at Aghia Kyriaki, Pagona (?) and Teichos Dymaion, Achaea appears to have followeda path of internal changes, within a mostly peaceful environment. With the completion of the features of Phase 1 at the beginning of LH IIIC Early, the twomentioned horizons (e.g. the continuing Argive tradition) had already transformed rapidly andthey constituted together a local formation with two different centres of progress. These twoSubmycenaean. Recently, a F type sword was found in an extremely rich warrior burial at Kouvaras (Akarnania) of LH IIICLate or Early Submycenaean date (Stavropoulou-Gatsi 2008). 35Two from Diakata and one from Lakkithra, all of Sandars type F (Sandars 1963, p. 151; Souyoudzoglou-Haywood1999, p. 77, pl. 20: A 837a, A 1167); the daggers from Diakata are of LH IIIC Late date or Early Submycenaean; a G typedagger is believed to be from Ithaca (LH IIIC Late or later) (Kilian-Dirlmeier 1993, p. 49, no. 103, pl. 19, 103; cf. Driessen,MacDonald1984, pp. 62-63, 74, fig. 6. P. Kalligas [1981, p. 82] suggests a Cephallenian origin). 36Several LH IIIB-C daggers of Sandars types E, F and G. From Mazaraki, Zitsa, see Papadopoulos 1998a, p. 27, no. 128,pl. 21, 128; from Kalbaki, ibid., p. 26, no. 119, pl. 19, 119; from Kastritsa, ibid. p. 26, no. 120, pl. 19, 120; from Elaphotopos,ibid., p. 26, no. 122, pl. 20, 122; from Dodone, Carapanos Collection, ibid., pp. 25-26, no. 118, pl. 19:118; from Mesopotamos,ibid., p. 26, no. 121, pl. 19, 121; cf. Kilian-Dirlmeier 1993, p. 82ff.; a LH IIIC date is suggested by Desborough (1972b, pp.95-97); a dagger from Paramythia dates back to LH IIIA 2 (Papadopoulos 1998a, pp. 22-23, no. 102, pl. 16, 102). 37Gonnoi, Dranitsa, Hexalophos, Elateia, Delphi; for references see Eder 1999a; Ead. 1999b; Ead. 2001, p. 77ff. 38The two daggers from Ancient Elis (supra, note 33), perhaps the two from Diakata and the one from Ithaca (supra, note 35). 39For two fragments of a possible Naue II type sword at Polis, Ithaca, see Catling 1956, p. 118, no. 29; Wardle 1972, p.238; Souyoudzoglou-Haywood 1999, p. 108. 40From Alpheiousa without a clear context, see Vikatou 1996, p. 194, pl. 62; one more is found in Elis, as I was kindlyinformed by O. Vikatou. Other types of swords that were known in the region, two swords from Lakkathela near Daphni, oneof Sandars type C, are briefly reported (LH IIIA) (Arapogianni 1998, pp. 225-226, pl. 92); a sword at Aghia Triada from awarrior burial with spears, a razor and phialae (Whitley 2003, p. 37, fig. 65).352

- 9. SOCIAL RE-ORGANIZATION AND RECONSTRUCTIONcentres are easy to distinguish in the local pottery. They evolved together, sharing their ownfeatures. Then each one modifies or develops the borrowed elements and this is how they fol-low together an unceasing creative cycle. Even though someone who studies the pottery of thisspecific phase is under the impression that it has homogeneous features, nonetheless the two dif-ferent approaches coexist, and disappear only when in other parts of the Mycenaean world LHIIIC Developed has already started. Together, they form the Early Achaean Style (Papazoglou-Manioudaki 1994, p. 189ff.; Mountjoy 1999, p. 404; Moschos 2002, p. 24, fig. 7), which prevailedin the province of Patras and influenced the pottery production at Dyme, at Kalavryta and as far asElis. This stylistic group that has clear time limits, I have named Achaean Phase 241 (tab. 1). On a social and administrative level, stability emerged with Phase 2 and probably there was adevelopment in the establishment of new forms of administration. However, the information thatwe have from the cemeteries is hardly enough, mainly because of the small number of primaryburials,42 so that the particular phase appears obscure on evidence level. A characteristic of thisperiod is the absence of burials that could have been connected with the superior administration,social organization or military hierarchy. An analogous image is to be seen in the rest of theMycenaean world. Despite of the fact that we do not have enough evidence in Achaea, howeverit would be intriguing to associate the absence of the elite with the consequences of the localdestructions of the previous phase. The Naue II type swords are still unknown in the area, which means that at least the localworkshops never became active in this sector, whereas the objects of Italian-related typology that weknew from the previous phase, either are not as many as in Phase 1 or we do not have safe evidencein order to determine their date. To be precise, there is no such object that can be dated with safetyto Phase 2 and in my opinion we do not have any more artifacts of Italian typology or Italian originin Achaea, a fact that may be connected with the distinctive absence of the elite from the tombs.It appears that after the destruction of Teichos Dymaion or more likely after a similar destructionin the province of Patras (Aghia Kyriaki and Pagona?), a temporary turmoil on local level wascaused, which had as an obvious effect the interruption of contacts with the Central Mediterranean;nevertheless the contacts with the Aegean were continued. It looks as if the technologies ofCentral Mediterranean origin were taken away from Achaea, as they did not have the time to beconsolidated in the brief Phase 1 and did not constitute a rooted and integral part of the local metallurgyproduction. This interruption probably suggests that the contacts in Phase 1 were, in particular, ofindirect Italian origin and the role of the refugees from the Argolid has already been highlighted.It would not be perhaps far from the truth to point out that the Italian technologies and the CentralEuropean contacts with the palatial centres have partly come with the refugees that reached Achaeain Phase 1. On the other hand, the sudden absence of rich burials that would be attributed to the local elitepossibly has to do also with the aversion to social ostentation through burial customs and archi-tecture, e.g. the aversion to the way which was known and still fresh from the palatial period.Whatever the reason was, the absence of burials like the ones that existed in the previous phase,perhaps, gives a good indication that during the LH IIIC Early a modified old cycle of administra-tion was completed. 41Moschos forthcoming; for Phase 2 at Klauss see Paschalidis, McGeorge in this volume. 42The classification of Klauss burials according to the Phase system can be also indicative of the burials number for eachPhase in the entire Achaea region; see Paschalidis, McGeorge in this volume. 353

- 10. Ioannis Moschos The stylistic group of pottery and the developed or modified Argolid horizon, the criticalattitude towards ostentation of palatial burial customs, the reduction or absence of the CentralEuropean features in the local metallurgy, and mainly the internal evolution of society andadministration, were definitely being completed at the start of the LH IIIC Middle. As a result, theperiod which follows shows the greatest prosperity in Western Achaea. In pottery we detectthe culmination of the Early Achaean Style and the appearance of the Late or Mature Style(Moschos 2002, pp. 24-25). Sometimes, the features are so mixed that it becomes almostimpossible to ascribe a vase to either style. Together they constitute the general characteristics ofa specific local style which has to be seen within LH IIIC Middle, and has to be called AchaeanPhase 343 (tab. 1). Modified survivals of the Early Style are present for the last time and theycompletely disappear just before the end of LH IIIC Advanced. The Late Style now begins to form itscharacteristics, which are completed and utterly dominate at the end of LH IIIC Advanced;44moreover, it totally pushes aside the Early Style. The beginning of its domination is a shortstylistic phase that we can call Achaean Phase 445 (tab. 1), and functions as a transition from LH IIICMiddle to LH IIIC Late, to which it actually belongs. We could say that in terms of style it constitutesthe answer of Achaea to the Close Style which already had an effect on Phase 3 pottery. After the brief transitional Phase 4 another stylistic phase in pottery production appeared, whichcovered the greater part of the LH IIIC Late period and constitutes the Achaean Phase 546 (tab. 1). Itis the acme of the Late Style and presents the most distinguished local pottery production of Achaeawith several exports to mainly neighbouring regions, but also with influences on pottery productionoutside of Western Achaea and as far as Italy, mostly the region of Apulia. This phase was over,I believe, shortly before the end of the traditional Late Phase, as outside factors, perhaps relatedto the ensuing collapse of the system and the downfall of Mycenaean civilization, had alreadyappeared. It would be safe to argue that the LH IIIC Late has no significant or decisive changes inthe social and administrative realm. If the middle part of the LH IIIC Middle was the climax of theMycenaean civilization in Achaea,47 the rest of the period until the end of the LH IIIC should beseen as the time during which the benefits were enjoyed. The influence of Minoan pottery on that of the Achaeans seems considerable during Phases3 and 4, though we lack a more specific study on the matter.48 Based on pottery production, wecan detect the settlement of Cretan potters49 somewhere in mountainous Elis, perhaps in the area 43Moschos forthcoming. For some of the features of the typology and themes repertoires, as they appear in the more recentexcavations of Klauss, see Paschalidis, McGeorge in this volume; see also Deger-Jalkotzy 2007 for similar features inElateia. 44Early traits of the Mature Style scarcely appear already by Phase 2; see Moschos 2002, p. 24. 45See Moschos forthcoming; Paschalidis, McGeorge in this volume. Pottery of this particular phase exists also in Elateia,for example in a LH IIIC Middle krater (Deger-Jalkotzy 2007, p. 159, fig. 11); a wheel-made bull figure from Amyklaion,Laconia, is of the same style (Demakopoulou 2007b, p. 165, fig. 17). 46See Moschos forthcoming; Deger-Jalkotzy 2007 (Elateia); for this style at Klauss see Paschalidis, McGeorge in thisvolume. 47The LH IIIC Middle appears to be the most important phase in several districts; see Muhly 1982, pp. 19-21; Deger-Jalkotzy 1994, p. 19. 48The Minoan influence is also proposed for the local production of Italo-Mycenaean pottery in Southern Italy; seeVagnetti 2003, p. 56f., with refs. 49The workshops presence is of a definitive importance for the evolution of local styles in Western Achaea and especiallyfor the formation of Late Style and explains its particular features. I have already suggested that Minoan craftsmen settled inthe region and operated a workshop in the congress Archeologia nel Mediterraneo. Ricerca, Tutela e Valorizzazione delle aree354

- 11. SOCIAL RE-ORGANIZATION AND RECONSTRUCTIONof Olympia, as Pausanias mentions.50 A conventionally named Mainland Minoan Workshop oper-ated here from the Middle51 until the Late Phase52 and the beginning of the Submycenaean. Itsproducts were luxury items including vases of the Octopus Style53 but also imitations of Minoanvessels that can hardly be identified as local products and told apart from Minoan imports. Potteryfrom this workshop has frequently been found at Elis, for example in the cemeteries of AghiaTriada and Kladeos.54 Also far away from the region of its production, as in the cemeteries ofKlauss (Mountjoy 1999, p. 427, fig. 149, 93) and Chalandritsa,55 near Patras, Portes (supra, notes51, 53; cf. Deger-Jalkotzy 2007, p. 132) and Spaliareika (Petropoulos 2000, pp. 75, 89, fig. 34, 10434; Moschos 2002, p. 26, pl. 1, 3) in the Dyme area, Palaiokastro56 in Arcadia, Krokeai inLaconia,57 Mycenae,58 Elateia (supra, note 49; cf. Dickinson 2006, p. 69) in Phocis and maybeeven as far as Rocavecchia59 in Apulia. Imitations of its LH IIIC Middle production are knownarcheologiche nel territorio dellEforia di Patrasso, Sesta Borsa Mediterranea del Turismo Archeologico, Universit degli Studidi Salerno, Paestum-Salerno 6-9 novembre 2003 (proceedings under publication); Salavoura (2005, p. 41) mentions Minoaninfluences on the Palaiokastro pottery ware which are ... probably attributed to influences from Laconia or even Messeniaand it is inferred that Perhaps it is not about imports but about imitation of a local workshop that adopts Minoan shapes ... Inreality, the aforementioned regions do not influence the Palaiokastro Minoanizing pottery in any way, and what the MainlandMinoan Workshop really adopts are the local shapes. At the same time, it contributes to the evolution of the local shapes anddecorative motifs; however the initiative is not taken by this workshop but by the local ones. The same views about imitation arerepeated in her PhD thesis (Salavoura 2007, pp. 414, 417, 427-431). In the end (p. 418) she leaves wide open the possibilityto have been manufactured on the spot by Cretan craftsmen and finally refers to a workshop (p. 431) that Obviously, one ormore Minoan craftsmen have worked in it. She also highlights the accurate view of Dickinson (2005, p. 58) about the presenceof Minoan craftsmen, although he thinks that the workshop is situated in Palaiokastro. The last conclusion of Salavoura (2007,p. 431) is barely coherent with the entire extensive development of the subject and moreover it is not substantiated by her text.For a FS 175 imported octopus stirrup-jar at Elateia with glass bead inlays a clear feature of pottery production at Elis seeDeger-Jalkotzy 2007, pp. 131-132, figs. 1, 7; 2, 5. 50The mythical impact of this installation is preserved in Pausanias who registers the presence of Kurites in the Olympiaregion: Paus. V, 7, 6 and 8, 1. 51For a stirrup-jar at Portes see Moschos 2007b, fig. 27; for a three-legged pyxis and a footed stirrup-jar from Kladeos:Trypes, Elis, see Vikatou, Karageorghis 2006, figs. 5 ( 8034), 6 ( 8035); their date is LH IIIC Middle (Phase 3) and notLate (ibid., p. 160). 52Its production in this phase has nothing to do with the Minoan features of the workshops activity in the Middle phase.Furthermore, it is clear that in this period there is no direct contact with the developments in the Cretan pottery. A triple kernoswith a stirrup-jar and two stirrup-jars-like vessels from Aghia Triada, Elis (Vikatou 1999, pp. 243-244, fig. 12), belong to itsLH IIIC Late production. 53An unpublished stirrup-jar from Portes has an exact parallel at Palaiokastro and without doubt these vases have beenmade by the same craftsman; see Spyropoulos 1995, fig. on p. 17; cf. Salavoura 2007, pp. 413-414, fig. 109; see also supra,note 49. For other twin vases of the Octopus Style during the LH IIIC period see Vlachopoulos 2006b, p. 179ff., esp. pp.189-191. 54For Kladeos, Trypes, see Vikatou 1998, pls. 94 ( 7608), 95 ( 7263), 95 ( 7617), 96 (no. 8034), 97 ( 8074), 97( 8070); Mountjoy 1999, pp. 391, 393, 395, figs. 136, 73 (Phase 3), 138, 88 (Phase 4); see also supra, notes 51, 52, and infra,notes 59, 140; a straight-sided alabastron from Kaukania (Mountjoy 1999, fig. 138, 85) is an imitation by a local workshop. 55Among them a partly preserved duck askos; see Stavropoulou-Gatsi 1995, p. 217, pl. 82. 56See supra, notes 49, 53. An elaborate FS 175 stirrup-jar with pictorial decoration and the characteristic Cretan continuedencircling band around the spout, the false neck base and the handles; see Salavoura 2007, pp. 396-398, fig. 105. 57A triple askoid vessel of Phase 5; see Demakopoulou 2007b, p. 166, fig. 19. P.A. Mountjoy (1999, p. 293) refers tounpublished parallels in decoration from Palaiokastro. 58Probably a sherd from the body of a two-handled amphoriskos (FS 59 and not FS 61 as proposed in the publication) ofLH IIIC Middle date (Achaean Phase 3) (Demakopoulou 1990, p. 344, no. 323). 59Some sherds of Achaean type storage jar [Pagliara, Guglielmino 2005, p. 310 (II.200)]. As far as I can see from thephoto the fabric is the same. Furthermore, the well-known shape construction in combination with the less successful deco- 355

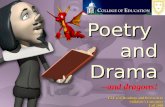

- 12. Ioannis Moschosfrom several local workshops in Achaea and Elis.60 The local elite seems to have been connectedwith this workshop during the LH IIIC Middle period in the way that was connected with theaforementioned local Argolid horizon of pottery production, during the LH IIIB Final/IIICEarly (Phase 1). During Phase 3, the reconstruction is established. Based on very little evidence from Phase 2,it is not easy to prove the sequence of these changes based only on the burial evidence. What wecan understand, though, is the constant and evolving course of administrative structures, whichwere certainly completed and established after the beginning of the LH IIIC Middle. Phase 3 isthe period with the wealthiest burials in Achaea, found in the cemeteries of Kallithea,61 nearPatras, and Portes,62 at the border with Elis. The burials belonged to warriors/officials and wereaccompanied by Naue II type swords, pottery, bronze implements and weaponry, includinggreaves. The thing that separates them from other burials of the same phase which were accom-panied by Naue II type swords was the precious object that was discovered with them: a bronzeplated helmet/tiara. The headgear from Portes is well-preserved (fig. 1). It is cylindrical in shape with an ovalsection and straight sides. Its preserved height is 0,158m, its width is 0.187-0.191m and its lengthis 0.23-0.236m. The surface is beautifully decorated with bronze strips consisting of horizontalribs that alternate with single horizontal rows of ornamental rivets that have a hemispherical head.These strips and rivets are exactly the same as the published ones from Kallithea, which wereconsidered to be fastened onto a corslet. The two ends are dressed with wider bronze bands thatbear relief ridges at the edges. The band of the top is decorated on the face by three nipples (fig.1a). The lower wide bronze ring of the helmet is known to Homer as .63ration (quirk, cross-hatched triangle, semi-circles?) is a distinguishable feature of the Mainland Minoan Workshop duringPhases 4 and 5. For the use of quirk as a filling motive in the Minoan pottery, it is suitable the example on the shoulder of aMinoan stirrup-jar from Ialysos (LM IIIC Early) (Mountjoy 1999, p. 986, pl. 8f). The quirk with dots was in the workshopsrepertoire from Phase 3. A good example is to be found on the belly zone of a stirrup-jar from Kladeos: Trypes, Elis, whichis a Phase 3 product of the Mainland Minoan Workshop; see Vikatou, Karageorghis 2006, fig. 6 ( 8035). Of about thesame date (Phase 3 to 4) and from the same workshop is the quirk on a high body alabastron from Kladeos, see Vikatou1998, pl. 94 ( 7178). As an influence of the Mainland Minoan Workshop on the local pottery of Palaiokastro, the samequirk appears on the belly decoration of a huge stirrup-jar (LH IIIC Late/Phase 5); see Mountjoy 1999, 298, pl. 1a. For thetriangle see ibid., fig. 149, 92 (Klauss). 60For example, a stirrup-jar from Spaliareika [Petropoulos 2000, p. 75, fig. 33 ( 9880)]. Probably from the same work-shop is a juglet from Klauss (Paschalidis, McGeorge in this volume); few unpublished stirrup-jars from Voudeni; two of themare also imitating the yellowish slip. The same is valid for two vases from the newly excavated tombs at Krini: Zoetada (kindinformation of S. Kaskantiri). 61Yalouris 1960; Papadopoulos 1978-1979, p. 166, pls. 320a-b, 355c-d, 356a-b; Kolonas 2001, p. 261, note 19;Papadopoulos, Kontorli-Papadopoulou 2001, p. 134; Moschos 2002, pp. 29-30, fig. 10, 1-2; Deger-Jalkotzy 2006, p. 160;Moschos 2007b, pp. 24-25, fig. 17; its date falls into Achaean Phase 3 and is contemporary with the warrior burial at Portes.The pedestal stirrup-jar from the warrior burial at Kallithea (Mountjoy 1999, p. 427, fig. 150, 96) is typical of this phase and isrelated with the Early Achaean Style. The introduction of the shape into the Achaean repertoire is due to the Mainland MinoanWorkshop. This shape is also adopted by the Mature Achaean Style and survives in Achaean Phase 4, whilst it is extremely rarein Phase 5; see Moschos forthcoming. 62Kolonas, Moschos 1995, p. 218; Kolonas 1996, p. 7; Id. 1998a, pp. 474-475; Id. 2001, pp. 260-261; Id. 2006, p. 223;Papadopoulos 1999, p. 271, pl. LIXb; Papadopoulos, Kontorli-Papadopoulou 2001, pp. 134, 136, fig. 24; Iid. 2003, p. 83,figs. 106, 107; Moschos 2002, pp. 29-30; Id. 2007a, pp. 287-288; Id. 2007b, p. 31; Papazoglou-Manioudaki 2003, p. 440,note 90; Eder, Jung 2005, p. 489; Deger-Jalkotzy 2006, p. 159. 63Il. 12; 30; 96. For a good parallel of on a sherd from Mycenae, see Slenczka 1974, pl. 9, 4; Vermeule,Karageorghis 1982, no. XI.47.356

- 13. SOCIAL RE-ORGANIZATION AND RECONSTRUCTION a. b.Fig. 1. - The helmet of the Portes warrior; a. Front view. b. Side view. LH IIIC Middle (Achaean Phase 3). h 0.158, w 0.187-0.191, l 0.23-0.236m (Photos by P. Konstantopoulos). 357

- 14. Ioannis Moschos All these separate strips and bands, sixteen in total, and the rivets could not be firmly fixedand kept in position unless they leaned on an inside headgear. Contrary to our expectations whenreading Homer, we found out that it was not a leather but a plain straw hat, tightly knitted(fig. 2a). Of course, it was in the shape of the helmet, that is oval cylindrical. Its closed top was notsalvaged, however enough evidence was preserved to assume with absolute certainty that it wascurved, consisting of the only visible section of the straw hat which was slightly projecting overthe bronze lining. The curved straw top must have been shaped like the closest parallel of Portesand Kallithea helmets in iconography, on a pictorial fragment from Kos, although the latter issurmounted by a crest of tall rays as the feathered Philistine head-dress (Vermeule, Karageorghis1982, p. 160, XII.29 on the right; cf. Mountjoy 2005, p. 425, pl. 98f). We could say that the straw bed is an adaptation to the needs of the design,64 but still a simplevariation of the known helmet of the period with the fringed frame, which also wear the warriorswhile in action on the krater of warriors from Mycenae. This helmet is the most repeated inthe LH IIIC representations and is the only one known in the Voudeni iconography. It is not atall strange to consider that we have a common helmet made of straw, such as the majority ofhelmets of this type.65 In the representations they are seen with a more curved top and seem almostsquat since there was no reason for them to be cylindrical. The straw helmet of Portes acquired acylindrical shape which was known by the helmets of the Sea Peoples, with unique aim its coating;therefore, it would become a luxurious and distinguished object. Apparently, this helmet notonly was intended for use in combat, but it also was used as a ceremonial emblem of power, aninsigne dignitatis.66 Parallels are known from Lakkithra, Cephalonia67 (fig. 2b), and Photoula, Praesos, Crete,68 notidentified until recently. Two fragments of bronze sheet bands from Phaestos (Savignoni 1904, pp.538-539, figs. 22 and esp. 23; Yalouris 1960, pp. 53, 59) and four others from the ChT cemeteryat Mycenae (Yalouris 1960, p. 59, pl. 25, 2-3; Xenaki-Sakellariou 1985, pp. 78, no. 2781; 200,no. 3034, pls. 13, 89) have been identified as belts, parts of corselets and mitrae; if so, someof them might have been served as the precursors of the Achaean lined headgears. The entire construction could be described as according to which wasHectors helmet (Il. 373). It is reminiscent of the lower part of the Sea People headgear in thebattle relief in the mortuary temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu (ca. 1176-1172 B.C.) nearLuxor (Nelson, Hlscher, Wilson 1930, pl. 37; Drews 2000, pp. 184-190; Wachsmann 1998, p.169, fig. 8, 10). 64It was also for comfort; a felt or a leather cap (pilos) was sewn in Corinthian bronze helmets; see Cartledge 1977, p.14. 65On the use of leather and bronze see the discussion in Mountjoy 2005, pp. 425-426. Helmets of perishable material seemto be the most common type in G tombs until the end of the 8th c. B.C.; see Lorimer 1950, p. 233. 66It is not a crown, as has been recently suggested, because its top was not open and that demonstrates concern for protectionand potential to use it in war operations; see Deger-Jalkotzy 2006, p. 159; survivals of later date are known; they can be consid-ered emblems of religious authority, like for example the ivory statuette from Ephesos that dates back to the end of 7th cent. B.C.;see Akurgal 1961, pp. 196-197, figs. 155-157. The representation of a bronze situla with two handles dating to the 6th-5th c. B.C.from Welzelach im Virgental on the Alps shows analogous decorative traits; see Gleirscher 1991, pp. 51-52, fig. 25. 67Marinatos 1932, p. 39, pl. 16; Moschos 2007a, p. 288. A.F. Harding (1984, p. 174) wrongly relates the bronze stripesand nails to a leather cuirass. Analogous was also the identification of the object from Kallithea in the older publications. 68Platon 1960, pp. 304-305, pl. 241; cf. Kanta 1980, p. 181; Ead. 2003a, p. 180; Deger-Jalkotzy 2006, pp. 159, 164-165. In the first publications the object was identified as a bucket.358

- 15. SOCIAL RE-ORGANIZATION AND RECONSTRUCTION a. b.Fig. 2. - a. Portes: The straw bed of the helmet (photo by L. Paulatos). b. Bronze bands and nails from the hel- met of Lakkithra, Cephalonia (photo by A. Soteriou). 359

- 16. Ioannis Moschos The information derived from these two Achaean burials mostly relates to military organizationand hierarchy, but it also reflects aspects of the social and administrative stratification of the LHIIIC Middle phase. As a matter of fact, we obtain the profound military aspect of the authoritywhich has been crystallized in the epics by taking the form of military monarchy. However, eventhere one could validly claim that this authority is mainly related with the evolution of the mythand therefore is placed in another sphere, beyond the real and historic one. The warriors/officialsof Achaea, of Cephalonia and of Crete reveal that this sphere not only was poetic but also realand historic.69 Similar data for this specific period are rarely found outside Achaea. These data cover themiddle part of the LH IIIC Middle, to which belong the earliest warrior burials with Naue II typeswords. Analogous burials occurred in the following Phases 4 and 5 too, so we can argue that onthe basis of this and other presumptions, the existing model of organization was operating at leastuntil during the LH IIIC Late and, in my view, at least as late as Early Submycenaean (Phase 6a,see infra), which is a transitional era for the formation of substantial changes in the political andorganizational structures that apply and operate completely in the Submycenaean period (Phase6b, see infra). The supreme form of authority that we know of, for the time being, is related to burials ofwarriors/officials of Kallithea and Portes.70 The warriors with Naue II type swords would havehad a lower rank and have enjoyed great respect from society.71 Some of them are accompaniedby jewellery and objects of personal use, while other weapons, more often spear heads, as wellas implements such as knives, composed the standard equipment. The pottery that accompaniedthem was sometimes of an excellent quality and it is likely that its acquisition cost even more.These warrior burials find their close parallels in Eastern Crete and in a cremation burial atFrattesina Narde72 (T 227), which seems to be the richest in Italy. A line of warriors on foot like the above mentioned is depicted on the krater of Thermos(Wardle, Wardle 2003, p. 150, fig. 3), which comes from the Painter of the warriors, with Naue IItype swords of the Voudeni workshop.73 All the warriors seem to belong to the same rank and bear 69... may well be viewed as a step along the line of development from Mycenaean qa-si-re-we to the Homeric basileis(Deger-Jalkotzy 2006, p. 176); cf. Eder, Jung 2005, p. 486; Eder 2006, p. 572. For Homeric basileis see Barcel 1993, pp.32-35, 55-71. 70... the most important burials are those of the well-greaved warriors of Kallithea and Portes, which belong not to ordi-nary soldiers but to high-status militant Mycenaeans (Papadopoulos, Kontorli-Papadopoulou 2001, p. 134); cf. Moschos2002, p. 30. 71So far, the total number of the Naue II type swords in Achaea adds up to 17. Five of these are still to be mentioned inreports. For the published ones, see Catling 1956, pp. 111-112, nos. 6-8; Vermeule 1960, pp. 14-15; Yalouris 1960, pp. 43-44,pls. 27, 1-2, 31, 1-2; Papadopoulos 1978-1979, p. 166, figs. 320, 355c-d, 356; Id. 1984, p. 221ff., fig. 2, pl. 29; Id. 1991b, pp.81, 83, pl. 48; Id. 1999, p. 268ff., pls. 56d, 57b, 58a-d; Bouzek 1985, p. 122ff.; Petropoulos 1990c, p. 133; Id. 2000, pp. 68f.,73f., fig. 41; Id. 2006, p. 41; Id. 2007, pp. 260, 263-264, fig. 87; Drews 1993, p. 203; Papazoglou-Manioudaki 1994, pp. 177-182, figs. 3-6, pls. 26a-c, 27a-b, 28a; Kolonas 2000, p. 96, fig. 3; Id. 2001, p. 261; Papadopoulos, Kontorli-Papadopoulou2001, p. 134, figs. 22, 23, 28; Moschos 2002, pp. 29-30, fig. 10, pl. 1, 4; Id. 2007a, pp. 287-288; Eder 2003a, 38-41; Eder,Jung 2005, pp. 490-491, pl. 107; Deger-Jalkotzy 2006, pp. 157-161, 165ff.; Jung 2006, p. 204ff.; Vlachopoulos 2006a, p.260; Paschalidis, McGeorge in this volume. 72Salzani 1989, pp. 16-17, 38-39, figs. 16-17; LH IIIC pottery from the site has been imported from Western Greece; seethe discussion in Eder 2003a, pp. 44-45, note 60. 73Kolonas forthcoming; Dietz, Moschos 2006, p. 60. For other warrior illustrations during LH IIIC, see Eder 2003a, p.39, note 10.360

- 17. SOCIAL RE-ORGANIZATION AND RECONSTRUCTIONNaue II swords in leather scabbards, with leather strings74 attached to them. The swords are placedaround the shoulders, in a similar manner to that described by Homer concerning Agamemnonand Achilles (Il. 29, 372). They wear a short fringed chiton and details were rendered byadded white, as in Voudeni, too. Unfortunately, the depiction of their leader was not salvaged, ifthere was one, but we still get a pretty clear picture of how members of the Achaean elite wouldappear on formal occasions. I have the impression that the theme of the aforementioned depictionis completely different from the departure of warriors on the well-known krater of Mycenae;75 itis exclusively related to the escort of warriors to a burial ritual.76 The most important part of thedepiction, perhaps, was on the other side (prothesis or ekphora of the dead?). The above stratification reflects social ranks on a local level. The forming of military ranks,with a corresponding social and administrative background, has to be considered a fact inperipheral settlements or groups of peripheral settlements (Moschos 2002, pp. 29-30; Id. 2007a, p.285; cf. Deger-Jalkotzy 2006, p. 169). These settlements do not seem to be anything other than theones that Pausanias preserves when he mentions the according to komas settlement facilities inAchaea.77 He refers to the number of 12 komae, a term that is used in a political context. This factindicates a larger number of settlement facilities or the administrative coalition of neighbouringfacilities into a kome, according to geographical criteria. On the other hand, the number 12 maynot be random, since it implies the perfection, completion and adequacy, in order to attach or toinsinuate upright descriptions concerning that system of political administration. The potentialpolitical geography and the partition in small political and administrative units, as a model thatis also implied in the myth, appear to be the most likely scenario for the LH IIIC Achaea and theeven farther Cephalonia. Elsewhere I have referred to the possibility that all these small LH IIIC administrative units,which have the form of a self governing geographical demographic cell, consist of a tight admin-istrative set under the form of provinces.78 This notion was already implied from the very begin- 74Traces of leather strings were probably found at Spaliareika; M. Petropoulos (2000, p. 76) refers to 22 very small bronzehemispherical heads; I believe that they were attached at the edge of the strings. 75Vermeule, Karageorghis 1982, pp. 130-132, XI.42; Sakellarakis 1992, pp. 36-37, no. 32. Its correlation with thefunerary customs is suggested by some scholars. It is characteristic the fact that the warriors carry spears and not Naue II typeswords, as they do in Voudeni and in the krater of Thermos. The same goes for the sherds of a krater depicting a chariot fromMycenae (one sherd in NAM, see Catling 1968, pl. 23, 19-19; cf. Sakellarakis 1992, p. 34, no. 28). Its decoration is enlistedto the same iconographical and stylistic group of Voudeni. For another scene of a warrior who carries a spear and not a Naue IItype sword from Mycenae see Sakellarakis 1992, p. 35, no. 40. Rail chariot warriors from Tiryns are armed with one or twospears; see Kilian 1982, p. 414, fig. 27; Gntner 2000. It might not be accidental that, so far, warrior burials with Naue II typeswords have not been discovered in Argolid; see Deger-Jalkotzy 2006, pp. 152, 168, 172. The three known swords of Mycenaecame from the excavations of the Acropolis and Tsountas Hoard, the two swords from Tiryns were found in the Tiryns Treasure;see Catling 1956, pp. 109-111, nos. 1-5; Koui et alii 2006. An exception could be the Schliemanns sword, which might havecame from a grave. A Naue II type sword is carried by the warrior in a fragmentary depiction at Lefkandi-Xeropolis: see Popham,Sackett 1968, fig. 39. 76The correlation of warriors with burial customs is evident in the painted stele at Mycenae: see Vermeule, Karageorghis1982, pp. 132-134, X.43; Immerwahr 1990, pp. 151ff. and 194; once again, they carry spears. 77Pausanias 7.1.1-9; 6.1-2. See Moschos 2002, p. 30; cf. Deger-Jalkotzy 1998b, pp. 124-125; Ead. 2006, p. 174 (sheprefers the political term damos). 78Moschos 2002, p. 17ff.; Id. 2007a, pp. 285-286, 289; S. Deger-Jalkotzy (1999, p. 129) claims that during the LH IIICperiod the political maps ... have been characterized by independent small-scale polities whose territories were in accordancewith the geomorphological conditions of Greece. 361

- 18. Ioannis Moschosning, when the delay of the Dyme province was mentioned in comparison with the one of Patrasand the start of re-organization of the latter before the destruction of Teichos. For this reason it issound to claim that the new administration system was put into practice right after the destructionsof the Mycenaean world. This phenomenon could be simply interpreted as further development ofthe palatial administration system, in which, basically for economic reasons, there were limitedperhaps, but at all events, clearly regional centralized administrative responsibilities to individualsand peripheries, where tholos tombs were found.79 This situation must have led during LH IIIB tothe formation of local elites whose characteristics on power level should have been different fromthe ones that characterize the LH IIIC period. Achaea, as a district of the Mycenaean world, awayfrom the powerful Mycenaean centres, should have implemented more profoundly a centralizedstructure of this decentralized administrative system during the palatial period. The geographicalbase of administration was already there but after the collapse its course was different from thepalatial model. This base of administration and its utterly altered survival are also the main reasonwhich makes us believe that Achaea was less affected by the direct consequences of the palatialadministration system collapse at the end of the 13th century. The presence of a local elite in LH IIIC Achaea has already been assumed, but its position in theregional scheme of administration remains unknown, as are the shape and form of central admin-istration. What we can be certain of is that power seems to be dispersed to the periphery, wheremilitary command has been assumed on a local level. Nevertheless, the military commanderwould, certainly, have enjoyed a broader authority of political and administrative nature. In Cephalonia the administrative and social framework seems to be similar to that of Achaea.In the aftermath of the destruction of the palaces, the island experienced widespread development,which is mainly reflected, but not exclusively, in the increased population and general prosperity,as documented by the burial evidence. LH IIIC Late is clearly the wealthiest and most importantperiod (Souyoudzoglou-Haywood 1999, p. 137ff.; Moschos 2007a, pp. 278-281, 284ff.), a timededicated in Achaea to the enjoyment of the benefits that the new order had offered. I shouldalso mention that power in Cephalonia appears to be decentralized during the LH IIIC period,probably separated into two to four organized cells of population or provinces (Kalligas 1995, pp.2-3; Soteriou 1995, p. 91; Moschos 2007a, pp. 279-280, 285ff.). Fragments of a helmet/tiara fromthe cemetery at Lakkithra (supra, note 67) (fig. 2b) reveal here the presence of local elite withmilitary and even political power. In the light of this evidence we have two different, mutuallydependent, geographic regions with a similar model of administration and power. On a regionallevel, the islands maritime role seems to have been promoted during this period. It is not onlypassing ships that bring wealth, but the fleet of the Cephallenes themselves, which follows the trendsand advantages of the new era. This is also reflected by the presence of the exotic amber80 whose 79Regarding the topic see Thomas 1995, pp. 353-354. As far as the tholos tombs are concerned in Achaea, see Moschos2002, pp. 27-28, notes 7, 51, with refs.; Papazoglou-Manioudaki 2003; add also a newly excavated tholos tomb at Portes(unpublished). 80There are at least 65 beads; see Souyoudzoglou-Haywood 1999, pp. 84-85; cf. Marinatos 1932, p. 42; Harding,Hughes-Brock 1974, p. 160; Eder 2003a, p. 47; Ead. 2006, p. 558, with refs.; Eder, Jung 2005, p. 489; Moschos 2007a,p. 289. One bead has to be added from ChT at Metaxata (unpublished, Argostoli Museum, catalogue no. 2065) and threemore from Diakata (AM catalogue nos. 834 and 835). The seven beads from Diakata reported by Souyoudzoglou-Haywood(1999, p. 84, note 545: AM catalogue no. 833) are not all amber beads. The amber trade went on without any problems duringthe Early Submycenaean and Submycenaean periods, as it can be seen in beads in ChT at Diakata (Kyparissis 1919, p. 116,fig. 30, 3) and in a bead in a pit grave at Ancient Elis (Yalouris 1961-1962, p. 125, pl. 146; Eder 2001, pp. 25, 92-93). For362

- 19. SOCIAL RE-ORGANIZATION AND RECONSTRUCTIONquantity during this period (LH IIIC) is larger than the amber that has been found in the rest ofthe Mycenaean world.The Submycenaean period and the political transformation Teichos Dymaion stands out among the destroyed fortified sites as in LH IIIC period it thrivedmore than in LH IIIB (for discussion see Deger-Jalkotzy 1995, p. 375ff.). This fact, maybe,explains the use of the area not as headquarters of the palatial authority but for other purposeswhich seem to have been continued without a hitch after the destruction. Although these purposeshave yet to be interpreted through excavation, it seems that they were the reason for a seconddestruction of the site (Mastrokostas 1965b, p. 121; Papadopoulos, Kontorli-Papadopoulou 2003,pp. 90-91), dating approximately from the end of the LH IIIC Late. Taking this into consideration,the most important and recognizable historical event in Western Achaea should not be consideredto be the confirmation of a synchronization with the general destruction, which at TeichosDymaion dates between the transition from the LH IIIB to the LH IIIC Early period (Mountjoy1999, p. 402) or, in my view, at the end of Phase 1, but the second destruction that might lead, inthe future, to solutions in problems of trade, economy and local administration. Furthermore, this destruction must have been selective or specific in character, since the exca-vated settlements at Pagona and Aghia Kyriaki near Patras and Chalandritsa: Stavros (Moschos2002, p. 19, note 7, P28; Kolonas, Gazis 2006) were not destroyed during this period. Nonewcomers have come to Teichos Dymaion, nor did the local population leave after the seconddestruction. All the above-mentioned settlements continued to exist until the Early Submycenaeanperiod, as many other settlements in Achaea, according to data that we have collected from thecemeteries of chamber tombs. But this disaster has to be seen as an historical fact that had aneffect on the life of the inhabitants of the region; so that it could be related to the beginning of anew phase in Western Achaea (Achaean Phase 6a: Moschos forthcoming; Deger-Jalkotzy 2007,p. 145; Paschalidis, McGeorge in this volume) and, in accordance with the archaeological data,could be applied to the whole Territory, but also to the whole Western Mainland Koine. This phase (Achaean Phase 6a, tab. 1) has to be seen either as an Early Submycenaean periodor as a slowly declining and lengthening LH IIIC Late. To be more precise, this transitionalcontemporary amber at Torre Castelluccia (Apulia), Bar, Kalbaki and Mazaraki, see Harding, Hughes-Brock 1974. Accordingto them (pp. 153, 159) amber is imported to Greece via the Adriatic trade and, as is stated by Souyoudzoglou-Haywood (1999,p. 85), the island of Cephalonia ... may even have played an active part in its distribution on the Mainland; cf. Eder 2003a,p. 48; Eder, Jung 2005, p. 489; Eder (2007b, p. 43) also pointed out Achaeas active role. Being all these true, however, therelations between Cephalonia and the Ambrakian Gulf probably indicate that in the latter there was an important terminal pointfor the dispersion of this precious material (amber), from Northern and Central Greece through land routes, or even sea routesvia Apulia to Adriatic coasts (Ilyria); see Palavestra 2007, for a recent attestation of the amber routes. For other relations ofthe Southern Adriatic with Apulia, see Bouzek 1994, p. 229, note 59, with refs. The presence of Achaea in Loutraki, Akarnania,maybe confirms this view. Other ports in Epirus, such as Kiperi-Xylokastro and Glykys Limin, perhaps constituted competitivefinancial places among local populations and not only for the alleged profitable trade of amber. This fact maybe justifies themovement of mountaineers groups towards south, for instance, to Thermos and mostly to Skaphidaki, Preveza, exactly at thenorthern entrance of the Ambrakian Gulf, mainly towards the end of the LH IIIC Late. For the amber that arrived at NorthernGreece via a northern route along the Danube, but moreover for the significance of the Vardar-Morava and Strymon valleys andfor the land relations of north and south, see Jung 2007a, p. 221ff.; Videski 2007; Czebreszuk 2007, pp. 367-368; see also theopposite view in Bouzek 1994, p. 221. 363