Historical aspects of patent systems

Transcript of Historical aspects of patent systems

IE F F T R A N S A C T I O N S ^ ! ^ P R O F E S S I O N A L COMMUN I C A T I O N i ' V Ô L . P C 22 . NO. 2. J U N t 1 9 7 9 59

Disclosure D o c u m e n t Program, j f lBs* Patent ^and Trademark Office Washington; D C 2 0 2 3 4 . 1 9 7 6 . free (Ρ)

T h e E m p l o y e d Inventor in the United States: R A D Pol ic ies , Law, and Practice., F. N>umeyër , with WgaJ analysis,cby J. C. S t e d m a n . M I T . Press, Cambridge . MA, l ? 7 t (B)

German Laws .Re la t ing to Patents , Uti l i ty Models , and Trademarks , and to Invent ions o f , E m p l o y e e s (in English.), 2nd éd . . J.-D. von U e x k u l l , Ed. . Carl Heyjnanns Verlajj, Koln , Vy. G e r m a n y , 1977 (B)

T h e German Patent Off ice (in G e r m a n ) , Carl H e y m a n n s Verlag, Ko ln , W. G e r m a n y . 1 9 7 7 (B)

The Granting o f Inventive R i g h t s , ] . W. Klooster , Intel-Lex Inc. . Minnea p o l i s , ^ , 1 9 6 5 (B)

Guide t o Patent , Trade Mark, and Copyr ight in Canada, Coles Publishing C o . , Lttf., T o r o n t o , Ontario, Canada. 1 9 7 7 (B)

H o w to. Get a European Patent , Guide for Appl i cant s , 2nd rev. ed . , European Patent Off ice , Postfach 2 0 2 0 2 0 , D - 8 0 0 0 . Munich 2 , West ' Germany ; available* in English, v E r e n c h , and G e r m a n , June 1 9 7 8 , free (P)

Intel lectual Property ' M a n a g e m e n t - L a w , Business , S tra tegy , P. Sperber, Clark, Boardman Co . . Ltd. , N e w York; 1975 (B)

Legal Aspec t s of T e c h n o l o g y Ut i l i zat ion , R. I. Miller. D. C. Heath and C o . . L e x i n g t o n , MA, 1 9 7 4 . (B)

b Mechanics o f Pi t ent 'Cla im Draft ing, ) ^ Landis , Practising Law Institute , N e w York, G l - 0 6 3 3 , 1 9 7 4 ( B ) ^

Patent ^Law and Protec t ion o f Invent ions (in G e r m a n F Epstein, Ver-lag fur cue Technische* Universitat Graz, Austria, 1977 (B)

Patent Law F u n d a m e n t a l s , P. D Rosenberg , Clark Boardman Co . , Ltd . , » N e w York, 1975 (B)

* Patent Laws, Supt . o f D o c u m e n t s , Govt . Printing Off ice , Washington, DC 2 0 4 0 2 . 0 0 3 - 0 0 4 - 0 0 5 3 5 - 1 , Aug 1 9 7 6 . 5 2 . 1 0 (B)

Patent Problems for Electronic 'Engineers (in German) , E. Zipse. F ranzis-Verlag, M u n i c h , W G e r m a n y , 1 9 7 4 (B)

ÇCT Appl icant ' s Guide , General Informat ion for Users o f the Patent C o o p e r a t i o n Treaty , World Intel lectual Property Organizat ion , G e n e v a , Swi tzer land . May 1 9 7 8 ( ? )

Trade Secrets , R. M. Milgrim, Matthew Bender and C o . , Inc . , N e w York , 1 9 7 6 (B) * . ,

U.S . Lags in Patent Law R e f o r m , G. P. Parsons, Spectrum, vol. 1 5 . n o . 3 . p. 6 0 , Mar. 1*^8 (J) · u ' '

Historical Aspects of Patent Systems HERMAN SKOLNIK

/ t J w r f u c r - N e w technolog ies arising from invent ions and d e v e l o p m e n t s have characterized every' k n o w n · c ivi l izat ion s m c e a n t i q u i t y . The c o n c e p t o f invent ion per se, however , evolved s l o w l y , from the grant ing o f franchises in ancient Greece to the granting o f m o n o p o l i e s by Florence and Venice in the I 5 t h ' c e n t u r y . Patent s y s t e m s as w e k n o w t h e m today arose from the laws o f England, France , G e r m a n y , and t h e United States from the 15th to the 1 8 t h ' c e n t u r y and from the more def init ive laws o f tfce 19 th century . T h e past d e c a d e has b e e n marked by the in troduct ion o f an international c lassi f icat ion s y s t e m and the c o n c e p t o f an international patent s y s t e m .

RECORDS -of early civilizations disclose a series of discoveries and inventions. Thousands of years before the

development of writing, which occurred about.2500 B.C., fire and its many applications had been discovered, the wheel had been conceived, animals had been domesticated, tools had been introduced, and humans had engaged in activities such as agriculture, miniflg, metallurgy, construction, and boat building. From the 'dawn of history until humans learned to write, broad-based civilizations were dependent on the discovery of nature's secrets and on technological inventions and improvements.

The pace of discovery and invention, extremely slow through-

Reprinted wi th permission from the Journal of Chemicai Informa

tion and Computer Sciences, vol . 17 , no . 3 , p. 1 1 9 , August 1 9 7 7 ; c o p y

right 1 9 7 7 by the American Chemical S o c i e t y , Washington, DC 2 0 0 3 6 . The author is Manager o f the Technical Informat ion Divis ion

o f Hercules Inc. , Research Center , Wi lmington , D E 1 9 8 9 9 , ( 3 0 2 ) 9 9 5 - 3 0 0 0 ; he is also Editor o f JCICS

out most of antiquity, accelerated appreciably with the emergence and development of the Greek civilization. Some of the many, inventions which came forth during the height of trie Greek civilization were the water clock (Ktesibios); balance, lever, endless screw (Archimedes); surveyor's instruments, water level, screw press (Heron); and others such as the water wheel for pumping water and grinding grain, and the catapult as a military weapon. History tells us that the governing body in Athens granted franchises to those who invented or introduced new products, such as a new dish based on a special recipe invented by a chef.

From the Roman empire, which succeeded the Greek civilization, came the introduction of road construction, public hygiene with the construction of aqueducts and sewers, a completely new concept of architecture, and hydraulic cement for constructing buildings. The hydraulic cement was made possible by the pozzalana sand near Rome-wi th the- downfall of Rome, the quality of this cement could not be matched until the invention of Portland cement in the 19th century.

Over the 13 centuries of the Greek and Roman civilizations, from about 900 B.C. to 400+ A.D., western society was transformed from small agricultural communities to states with Urge cities. This new social structure was based on extensive trade between cities and states and required services (such as water and sewers), transportation facilities, and industries. Thus arose a class of artisans with technical skills and technological knowledge. Even during the Middle Age», frorrr

6 0 I FF Κ T R A N S A C T I O N S ON P R O F E S S I O N A L C O M M U N I C A T I O N . VOL Κ 22. NO 2. J U N F 1979

about the 5th to the* 14th century, which we think of as the Dark Ages, especially from the 5th t6 the 9th,century, inventions continued to come forth, such as fireplaces with chimneys, hot air stoves, the horse stirrup, wheeled plow, horse harness (which led to oxen being replaced by horses for plowing), horseshoes, carnages, with springs for transporting people, canal-lock chamber, windmills\ ship rudder, compass, and weight-driven clock.

By the end of the 43th century, the beginning of the Renaissance, the idea-of inventions was invented. The Mediterranean area, and especially Italy, was dominant during the early part of the Renaissance. Outstanding metal, glass, and textile artisans and gunsmiths were^centered in various cities of Italy, such as Florence and Venice. ^ Tkt first record of a granted patent was that by the Repubbc of Florence in 1421 for a barge fitted with hoisting-gear to load and unload marble. This first granted patent rewarded the inventor with an exclusive three-year monopoly. The Republic of Venice, one of the most industrially and commercially active sites in Europe during t h e Ί 5th century, granted similar monopolies to foster new enterprises. These monopolies were called privileges, and the first was granted by the Senate of Venice to J\>hn Speyer in 1469 for a printing process. By 1550, more than 100 patents had been granted in Venice under its patent law of 1474, which, however, was more like our present concept of copyrights than of patents. «

Industrial and commercial dominance of the Mediterranean area did not last long. Two factors contributed to the diffusion of Italian technology: Italian craftsmen were rWsuaded ©r induced r̂ y lucrative offer* of privileges of rnonopol)t to bring their skills and knowledge to other European states. Religious persecution*and warfare in Italy further stimulated the migration of Italian craftsmen. During most of the period from the 15th through the 17th century, craftsmen and technologists were a highly mobile group throughout Europe and many settled in the -American colonies, going where the rewards were greatest. The granting of monopolies was the primary reward, but the reward was highly localized, and no invention of merit remained confined for long to one locality. Johann Gutenberg's invention of movable type in the 1450s, for example, spread from Mainz, where Gutenberg had his printing plant, throughout Europe within 30 years, all without gain to Gutenberg.

Monopoly, not invention, was the underlying principle of the patent concept, and originally the word "patent ," derived from the Latin titerae patentes, referred to a grant of a special license or privilege ^ y a monarch to a subject, usually of the noble class. English rulers, -over a period of about two centuries, exercised the monopoly principle as a right of the crown to grant charters, commissions, offices, titles, favors, sanctions, and the exclusive right to practice an art or trade; to the .making, using, or selling of a product; and to the regulation of trade.

This practice led to many abuses ancyiampered or prevented the introduction of new industries by anyone not of the favored class. Parliament revolted against the practice of the crown, but the granting of monopolies by the crown did not end until 1623 with the passage of the British act called the

Statute of Monopolies. m One of the main features of the Statute, the protection of inventions, was the major exception to the prohibition against the crown's granting of special privilege. Even 1o this day, English-law considers the granting of a patent to be the prerogative of the crown, i.e., it is a privilege, not a right of the inventor.

In the 1640s, after the crown's monopoly power was eliminated, English patents were granted tor 14 years with the requirement that they be directed to the creation of new

^aciustry. Written description* or drawings were not required. Specifications, written under the^hventor 's initiative, gradually became a relatively common practice. Specifications became a consistent practice, indeed, ^requirement, as à çesult of a patent suit in 1770, and not 6y.statute. In 1852, the British Patent Office ^was established with the assigned responsibility for the granting and publication of British patents. It was not until 1872, however, that the British Patent Office employed scientifically trained examiners; examination for novelty was initiated in 1905.

Patents were introduced in Çermany in 1484 and in France in 1543. Italy and Germany, being divided into small independent states, could offer no nationwide monopoly by which an inventor could be protected -from, infringement beyond the border of the city, except by the maintenance of secrecy. The first step toward a national sysJem was taken by France in 1699 with assignment of the French Royal Academy of Sciences to examine parents if such was required to resolve disputed claims.

Colonial America was predominantly agricultural. Less than ten percent of the population was employed in manufacturing. Because there was a need for new industries, colonial legislatures invoked the exercise of monopoly, but generally without the abuses of the English practice, to encourage manufacturing and to induce European manufacturers to settle in the colonies. The first.patent in Colonial America was granted in 1641 by t+ie Massachusetts General Court to Samuel Winslow for making salt "after a method invented by himself" for a period of ten years provided the process was operable within one year. Salt, being a necessity, was the subject of other granted patents in Plymouth (1641), Massachusetts (1652), Virginia (1660), New York (1661), Connecticut (1691), and South Carolina (1725) , each presumably by a new process, but without the need to prove it. Pennsylvania, which had rhore industries than the other colonies, surprisingly granted no patent until after the Revolution.

The Continental Congress · adopted a resolution in 1783 recommending the enactment by each state of Copyright Acts. All but one state did by 1787. These Acts were superseded by the United States Constitution of 1789 which empowered the Federal government ". . . To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries."

Congress passed the first U.S. Patent Act on April 10, 1790, which granted patents for up to 14 years and placed administrative responsibility for the granting of patents in the State Department. The first board of examiners consisted of Thomas Jefferson-Secretary of State, Henry Knox-Secretary of War,

S K O L N I K . H I S T O R I C A L ASPECTS O F P A T E N T S Y S T E M S 61

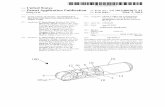

1 NOT.

Ekctrk4 Motor.

Να 7 m HWà Jew 7 , « 6 t

and Edmund Randolph-Attorney General. The Act required inventors to file a specification in writing, a drawing, and, if feasible, a model. The first patent granted under the Act w$s to Samuel Hopkins on July 31 , 1790, for "Making,Pot and Pearl Ashes."

By 1793, 57 patents has been granted. The current num-. bering system for U.S. patents was initiated in 1836; up to then, some 4000 patents had been issued. The number of patents issued per year by the U.S. Patent Office did not exceed 1000 until after 1850. On August 8, 1911, the one millionth patent was issued; the two millionth patent was issued on April 30, 1935; the three millionth patent was issued on September 12, 1961; and on the nation's bicentennial, July 4, 1976, U.S. Patent No. 3,958,115 was issued; this patent covers a "Combination Smoke and Heat Detector Alarm." The four millionth patent was issued on December 28, 1976, covering a "Process for Recycling Asphalt-Aggregate Compositions."

Administration of the 1790 Patent Act became burdensome to the board of examiners and Congress was asked to pass a new Patent Bill, which it did on February 4, 1793, to simplify the procedure and to eliminate the requirement for a patent to be sufficiently useful and important. This Act substantially made the granting of a patent a clerical operation. In 1802, the State Department established the Patent Office and appointed Dr. William Thornton, educated in medicine at Edinburgh, as its first superintendent. The Secretary of State remained the final authority on patent decisions.

The lack of definitiveness in and the ease of obtaining patents under the Patent Act of 1793 resulted in an overwhelming number of court litigations and encouraged Congress to pass a new Patent Act on July 4, 1836. The 1836 Act established the Patent Office and the Commissioner of Patents under the Secretary of State and required the systematic examination of patent applications. The 1836 Patent Act has been described as "a decided jump in advance of

anything . . . that had ever been proposed" and became "the standard practice for the whole world to emulate." The Act required that copies of issued patents be available, and that the patent include a short description of the invention and a statement specifying what was claimed. Patents were granted for 14 years, but the grant could be extended an additional seven years with the approval of the Secretary of State, the Solicitor o f the Treasury, and the Commissioner o f Patents.

That the Patent Act of 1836 was well conceived has been evidenced by the adoption o f its basic principles o f examination for novelty by other nations. The British did not examine for novelty until 1902; the French Patent Law of 1 791, which still is dominant, was primarily a registration system; the German system, which was introduced in 1877, shortly after the integration of the German states in 1871, combined examination for novelty with opposition and annulment procedures.

Subsequent patent legislation in the United States has been concerned for the most part with amplifications and clarifications. The first modification of the 1836 Act occurred in 1837 to allow the patentee who inadvertently claimed too much to file a disclaimer for the excessive portion. So that the Patent Office could handle its increasing work load, which resulted from the increasing number of patent specifications submitted, Congress authorized in 1839 an increase of staff. The 1839 legislation al$o required the publication of a classified list of granted patents. In 1848, the power to extend a patent grant from. 14 to 21 years was vested solely in the Commissioner's office, remaining there until 1861 when this became the right of Congress.

The Patent Act of 1861 extended the patent grant term to 17 years. The Patent Act of 1870, comprising 111 sections, was passed primarily to consolidate the 25 acts and laws that Congress passed between 1836 and 1870. One of the more important parts of the 1870 Act was the authorization for the printing of patents, laws, and decisions. This Act made

62 1 F E E T R A N S A C T I O N S O N P R O I - L S S I O N A L C O M M U N I C A T I O N . V O L . P C 2 2 , N O . 2 , J U N F . 1 9 7 9

printed patents available to the public at low cost. Amendments enacted since 1870, for the most part, have been concerned with matters of procedures, fees, and appropriations for the Patent Office. The Official Gazette was first issued in 1872. After 1880, a model was no longer required except as specifically requested by the Patent Office, such as for perpetual motion devices.

The first U.S. Patent Office classification of patents was initiated in 1830 with 16 classes. Try number of classes was increased to 22 in 1836 and to 36 in 1868. TJie revised classification system of 1872 had 145 classes and that of 1897 had 226^classes divided among 34 examining divisions. Congress passed an Act in 1898 which established the Classification Division and directed it to reclassify all prior art-foreign and domestic patents, and scientific publications. This assignment has yet to^be completed.

By statute, patent classification systems are to serve those who have the responsibility for examining patent applications. Thus, there i$ only one set of classified patents in ' the United States and that is in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Subject matter in U.S. patents is divided into about 350 main classes and 100,000 subclasses. 4 classification index contains about 50,000 alphabetic entries. Outmoded classes which are still active are replaced piecemeal by more modern classes.

Because the classification system is not aligned or in harmony with the disciplines and subdisciplines of science, it Ss necessary to scan hundreds of subclasses to cover a relatively restricted area of scientific interest. The basis for the* major classes is utility or use; the function or effect that is'performed or accomplished and the classification order of priority is as follows (the highest being 1):

1. Process of using the article or material 2. Article or material being used or manufactured 3. Process of making the article or material 4 . Machine for making the article or material 5. Composition or intermediate subcombinations.

Inasmuch as about one-half of the time of a patent examiner in the U.S. Patent Office is spent in the search for references in the prior art, the U.S. Patent Office has concentrated considerable attention on the potential of new information retrieval systems, with research and development annual budgets up to and several times over $500,000. The information retrieval problem still remains to be solved, although partial solutions are provided by Chemical Abstracts, Derwent k*blications (London) and IFI/Plenum Data Co., and by the various classification systems, such as the U.S., British, Gerrrfe^ and, more recently, the International Patent Classification.

Practically every country grants patents for inventior?&ind those which have an examination system also have a classification system. As patent systems evolved'over the past marly centuries, each nation went its own way Vi th differences in m * « \ t laws between nations so great that a universal system His beèfi considered impossible to achieve. * The Paris Conven-t i o n n T i 8 8 3 was successful, however, in establishing the right of priority for multinational filings. There is now a European patent system with a European Patent Office in Munich,

Germany, for examining applications and granting European patents. More than 600,000 applications per year currently are being processed in the various patent offices throughout the world. For example, of the approximately 65,000 patents granted yearly in the United States, about one-third are filed *' also in other nations, actually in four or five other nations on the average. This is an expensive and time-consuming process, as the obtaining of multinational protection requires knowledge of the maze of different laws, procedures, rules, practices, and philosophies of the patent systems of many nations, not to mention the need for translations into other languages. (For a current discussion of the European patenting system, see "Patenting U.S. Inventions Abroad, 1 ' ^his issue, pp. 122- < 125.

Substantial progress has been made in the development and increasing use of the International Patent Classification system. This objective was first initiated shortly after World War II and a working party was organized in 1952. The German patent classification was used initially as the basis inasmuch as many European nations had adopted\>r modified it for their classification systems. Furthermore, the German patent classification system was similar in many respects to that used in the United States in 1 872. Both followed the art orientation, although the U.S. patent classification starting in 1900 was based on function. The International Patent Classification, known now as IPC, as essentially completed in 1966 and adopted arid published in 1968, has some 46,000 subdivisions under eight sections, A through H, and is now being used by most nations either as the sole classification or in addition to their own. The U.S. Patent Office has been including IPC with issued patents since 1969.

Over the past 20 Or so years, there has been considerable activity among patent offices toward internal changes and international cooperation. For example, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland modified their laws to establish a unified patent law for the four countries. Since 1968, as pointed out above, most nations have been vusing the International Patent Classification. The important factor is that patent offices are acutely aware of existing problems and that these problems will be solved most expeditiously and economically through worldwide cooperation. No patent office in any country can cope adequately with the current patent documentation problems, and the ability to cope^ will become increasingly more difficult in the future. The final chapter in the history of patents will not be written until there is a truly international patent system.

B I B L I O G R A P H Y

" 1 7 5 t h Anniversary, U.S. Patent S y s t e m , 1 7 9 0 - 1 9 6 5 ; ' Proceedings, Vol . II, June 1 7 - l j 1 9 6 5 , P.T.C.R.I. Conference , and Oct . 1 7 - 2 0 , 1 9 6 5 , International A ssembl y , Patent Office S o c i e t y , Washington, D.C. , 1 9 6 6 , pp. 5 0 1 - 1 2 0 4 .

"Proceedings o f the International Patent Off ice Workshop o n Informat ion Retrieval ." Oct . 2 3 - 2 5 , 1 9 6 1 , Part II, U.S. G o v e r n m e n t PrinUjig Off ice , Washington, D.Cl, 1 9 6 2 , 2 3 7 pp.

"Concordance: U.S. Parent Classif ication to International Patent Class i f icat ion ," 2nd ed, Nov . 1 9 7 1 , Super intendent o f D o c u m e n t s , U ^ . Printing Off ice , Washington, D.C. 2 0 4 0 2 .

I. C. Baillie, "Where G o e s Europe? T h e E u r o p e a n . P a t e n t / ' J. Patent Office Soc., voL 5 8 , N o , 3 , 1 5 3 - 1 8 5 , 1 9 7 6 .

H I I rjlANSAC"! I O N S O N Γ K O I I S S I O N A 1 C O M M U N I C A T I O N . V O L . P C - 2 2 , N O . 2 . J U N L 1 9 7 9 6 3

1·'. J. Brenner. "The Challenges to the Patent S y s t e m s in the 1 9 7 0 \ , " / Patent Office Soc. vol. 5 3 , No . 7. pp. 4 0 7 - 4 2 2 , 1 9 7 1 . E. J. Brenner. "Patent I aw Revision. How Much D o We Really Need'.'." / Patent Office Soc, vol. 58 . No . 5. pp. 3 0 6 - 3 I 5. 1 9 7 6 . R. J. I ay. "Lull Text Information Retrieval ." ./. Patent Office Soc'.; vol. 5 3 . No . 9 , pp. 6 0 9 - 6 2 0 . 1 9 7 1 . P. J. I eder ico , " f o r e i g n Patent Material." / Patent Office Soe^. vol 5 4 . No . 3 . pp. 1 4 8 - 1 7 3 , 1972 . K T R l PAT 3rd Annual Meeting. Sept. 1 9 6 3 . Vienna. "Informat ion Retrieval-Patent Off ices ," Spartan Books . I . Lansing. Mich., 1 9 6 4 ; 4 t h Annual Meeting, Oct . 1964 , ' "Informat ion Retrieval A m o n g f \ -amining Patent Off ices ," H. Pfeffer. Ed., Spartan B oo k s . 1 9 6 6 . O. R. H. k n o p p , "The World's Major Patent S y s t e m s . " / Patent Office Soc., vol. 5 4 , No . 1, pp. 8 - 1 6 . 1 9 7 2 .

P. M. McDonnel l . "A New Approach to Mechanized Informat ion Retrieval in the U.S. Patent Of f i ce ." / Patent Office Soc, vol. 5 0 , No . 10 .VP- 6 5 1 - 6 5 8 . 1 9 6 8 . W. () . Ouesenberry . "Patent Cooperat ion Treaty. A Start Toward Modernizat ion of a 19th Century S y s t e m , " / Patent Office Soc, vol. 5 0 . pp. 5 0 9 - 5 1 8 , 1 9 6 8 . I. J. Rotk in , " Q u o Vadis- lnternatiowal Patent Class i f icat ion," / Patent Office Soc. vol 5 1 . No. 14 2, pp. 1 2 3 - 1 3 1 . 1 9 6 9 . Yt S. Turner. "Patent Literature," Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, vol 14 . Wiley, N e w York, N.Y. , 1 9 6 7 , pp. 5 8 3 - 6 3 5 . W. Wade, History of tiie American Patent Incentive S y s t e m , " / Patent Office Soc. vol. 5 4 . No. 1, pp. 6 7 - 7 1 , 1 9 7 2 . A'non., "A Patent Search for T e c h n o l o g y Trends ," Chem. Week, pp. 3 0 - 3 1 , July 28 . 1 9 7 6 .

The Plight of the Independent Inventor B Y R O N M V A N D E R B I L T

Abstract-The s i tuat ion o f the i n d e p e n d e n t inventor is compared with that o f a corporate inventor , and the value o f independent inventing is e m p h a s i z e d . Educat ion requirements , supplier pract ices , the not-invented-here a t t i tude , and Internal Revenue Service pol ic ies are said t o hamper the independent inventor . C o m i n g to his support are new assistance for invent ion marketing, inventor-or iented e d u c a t i o n , and the increasing overhead costs o f corporate research and d e v e l o p m e n t .

WHEN one reads an article about the national research and development (R&D) budget ($40 billion in 1977>,

the expenditures of industry, universities, research institutes, and government are listed. But not a word is mentioned about independent inventors to whom the U.S.Patent and Trademark Office grants about 16,000 patents a year.

Are the independents magicians who can invent without R&D? No, it is just one of the many fortuities in the life of the independent innovator. He is largely ignored by the R&D fraternity, the government, and big industry.

It is true that the independent has only practical objectives in mind and uses all the short cuts that he can. But to say that he does no research, or even basic research, is erroneous. An advance in applied research usually is accompanied by some new science or engineering, call it what you may.

Did not the independent Chester Carlson bring forth new science when he invented what we now know as xerography? Did not young Edwin Land, working in a rented room, create a new concept in technology when he produced practical light polarization by means of microscopic crystals oriented in a transparent matrix, the basis of most sunglasses today?

Reprinted w i t h permission from Industrial Research, vol . 2 0 , n o . 2 , p . 1 4 3 , February f 9 7 8 ; copyright 1 9 7 8 b y Dur/ -Donnel ley Publishing Corp . , Ch icago , IL 6 0 6 0 6 .

T h e author is a chemis t retired from E x x o n Research and Engineering C o . ; his address is P.O. B o x 1 1 7 7 , Green V a l l e y , AZ 8 5 6 1 4 , ( 6 0 2 ) 6 2 5 - 1 6 4 1 .

W H O I S A N I N D E P E N D E N T I N V E N T O R ?

First, let us define the independent we are talking about. He or she is basically an innovator who develops new things, about 74 percent of which are of a mechanical nature, based on U.S. patents not assigned. *

In the course of doing so, he may or may not get one or more patents. His product may be entirely new or an improvement of an existing product. Patents are the primary records we have of his accomplishments. Like Edison, the independent publishes little' in the scientific literature.

Differentiation between the independent and the corporate inventor provides additional definition. A major divider is this: The corporate inventor assigns his patents for a nominal fee to his employer, who finances his research; the independent, who finances his own research, owns his patents when issued. Both inventors may be working for someone else, but the independent would be doing research only as a sideline on his own time.

Carlson was employed as a patent lawyer when he got his early patents on xerography. Henry Ford was employed by Detroit Edison when he made his early improvements on the internal combustion engine. Alexander Bell was a'professor of speecrr at Boston College when he invented the telephone. Eugene Houdry, son of a wealthy family, had no j o b when he invented a practical method for the catalytic cracking o f petroleum.

The independent has no income from his inventing unless he is able to market or commercialize one or more o f his inventions. His counterpart in indAistry receives a salary, whether h ê successfully invents or not . Thus, unless he is wealthy, the independent must have other employment or must be in private business while he invents on the side. Most small shops and factories will allow an employee to work on his own time, using his o w n ideas.