The Marginal Utility of Income Richard Layard* Guy Mayraz* Steve Nickell** * CEP, London School of...

-

Upload

jocelyn-houston -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

3

Transcript of The Marginal Utility of Income Richard Layard* Guy Mayraz* Steve Nickell** * CEP, London School of...

The Marginal Utility of Income

Richard Layard*

Guy Mayraz*

Steve Nickell**

* CEP, London School of Economics

** Nuffield College, Oxford

• The marginal utility of income is a central concept in public economics

• The rate at which it declines is a very important number

• Given a CRRA utility function:

the parameter ρ (the coefficient of risk aversion) is a measure of this rate of decline.

• Our purpose is to estimate ρ

Goal

• Our method is very simple.

• First, treat answers (on a 1-10 scale) to the question “Taking all things into account, how happy are you these day?” as a measure of utility.

• Second, relate these answers to income in a cross-section or time-series analysis, and estimate the relevant parameters.

• Of course, the basic problem is how to persuade people that this procedure generates the parameters of interest.

Method

Alternative Methods

• Our method is based on attempting to measure ex-post “experienced” utility, which is what is required in this context.

• Alternative methods of estimating are based on studies of behaviour.

a) choice under uncertainty or b) intertemporal choice.

• Behaviour is assumed to be based on a decision function involving the weighted addition of ex-ante “decision” utility in different states or future time periods.

Problems with Alternative Methods

• Ex-ante “decision” utility often turns out to be systematically different from ex-post “experienced” utility.

• These methods involve dubious extraneous assumptions eg. Intertemporal additivity or expected utility maximization.

• Not surprisingly, they yield a very wide range of estimates of ρ - eg. Those based on choice under uncertainty range from 0 to 10.

• First, the use of overall “judgment” type questions (i.e. how happy or satisfied are you, all things considered?) may be questioned.

• The day reconstruction method (DRM) is an alternative (DRM involves dividing a day into episodes and in each, provide a rating on happiness, worry, frustration, etc. Then aggregate these into a combined score).

• Each has advantages and disadvantages.

• The measure we use is consistent with other meaningful measures of utility.

Measuring utility

• Second, what is the relationship between reported “happiness”, h, and true utility, u ?

• Normalising u so that 0 is the bottom level (extremely unhappy) and 10 is the top level (extremely happy), suppose h=f(u). Assume f’>0.

• Now consider three possibilities:

True utility and reported happiness

• Each individual has their own idiosyncratic interpretation of the scale. Thus the replies are not comparable:

hi= fi (ui)

• If true, it is hard to see how cross-sections yield rather precise relationships between h and variables such as income, employment status etc.

• Also, it is hard to see how, when person dummies are introduced into panel data (thus concentrating on time-series variation for each person), one obtains results which are similar to those generated by a cross-section.

The relationship between u and hFirst possibility

• Individuals use the scale in the same way, but potentially it reflects some non linear transformation of true utility:

hi= f(ui)

The relationship between u and hSecond possibility

Third possibility

• We investigate this, but initially we assume the third possibility.

hi= ui

• Same linear scale:

Data

• We use happiness scores or life satisfaction scores. We renormalise, if necessary, onto a 0-10 scale. If a survey contains both, we average.

• The income variable is total real household income, not equivalised, and sample members are restricted to those aged 30-55.

Reported happiness histogram

0.1

.2.3

0 2 4 6 8 10

HappinessEuropean Social Survey

Data (cont.)

• We use multiple years of four cross-section surveys:

– The US General Social Survey (GSS)– European Social Survey (ESS)– European Quality of Life Survey (EQLS)– World Values Survey (WVS)

• In addition we use two panel surveys:– German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP)– British Household Panel Survey (BHPS)

Data (cont.)

• Because we are estimating a direct utility function, we must include an hours of work variable.

• In addition we include standard controls:– Sex– Age (years + quadratic)– Education (years + quadratic or attainment level

dummies)– Marital status dummies– Employment status dummies– Country Dummies– Year dummies

Strategy

• Maintained model

( )it ith f u

( )it ct it j ijt i ct itj

u g y

individual, time, countryi t c

Strategy (cont.)

• Assuming hit= uit

– Cross-section analysis (assuming ρ=1)

– Panel analysis (assuming ρ=1)

– Estimation of ρ

• Investigation of the form of f

55.

56

6.5

7R

epor

ted

subj

ectiv

e w

ell-

bein

g

0 50000 100000 150000Household income (2004 dollars)

Source: General Social survey 1972-2004. All subjects. No controls.

Reported happiness as a function of income

Fig. 2: The simple cross-sectional relationship between reported happiness and income in the US General Social Survey.

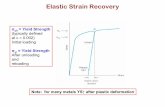

h vs. log y in cross-sections• The result is that reported happiness is approximately linear in

log income.

• Subjects with extreme incomes (5% on either side) deviate from general relationship, but this may reflect yearly blips or measurement problems.

• If we exclude observations with sharp change in reported income, the remaining observations fit the linear relationship well.

• However, introducing a quadratic term suggests a further degree of concavity.

• Panel analysis with fixed effects yields similar results.

-1-.

50

.51

-2 -1 0 1 2

General Social Survey

-1-.

50

.51

-2 -1 0 1 2

World Values Survey-1

-.5

0.5

1

-2 -1 0 1 2

European Social Survey

-1-.

50

.51

-2 -1 0 1 2

European Quality of Life Survey

-1-.

50

.51

-2 -1 0 1 2

German Socio-Economic Panel

-1-.

50

.51

-2 -1 0 1 2

British Household Panel Survey

-1-.

50

.51

-2 -1 0 1 2

German Socio-Economic Panel-1

-.5

0.5

1

-2 -1 0 1 2

British Household Panel Survey

Fig. 3: The partial relationship between reported happiness (y-axis) and log income (x-axis). FE indicates person fixed-effects were included in the regression. The graphs show a consistent near-linear relationship, with some variation in the slopes.

Table 3: Partial regression coefficients of happiness on log relative income and log relative income squared (t-scores in parentheses). Relative income is relative to mean income in country/year. Country/year dummies and other personal controls are included but not shown. Survey Log (y/ym) Log2 (y/ym) General Social Survey 0.70 (14.0) -0.07 (1.7) World Values Survey 0.62 (26.1) -0.09 (3.7) European Social Survey 0.59 (24.9) -0.15 (5.8) European Quality of Life Survey 0.81 (17.4) -0.08 (1.5) German Socio-Economic Panel (no fixed effects) 0.55 (27.2) -0.10 (2.7) British Household Panel Survey (no fixed effects) 0.35 (14.0) -0.06 (2.6) German Socio-Economic Panel (panel fixed effects) 0.36 (11.0) -0.08 (0.1) British Household Panel Survey (panel fixed effects) 0.25 (6.7) -0.10 (3.5)

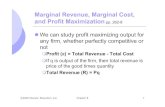

Estimating ρ

• Reported happiness is modelled as linear in a CRRA function with parameter ρ (see eq. 7)

• We plot the log likelihood of the observations as a function of ρ.

• We combine the datasets to produce the overall maximum likelihood estimate of ρ.

• MLE is ρ = 1.26.

Table 4: Maximum likelihood estimates of ρ in different surveys using first the linear dependent variable model, and then ordered logit. 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. Survey Standard estimate Ordered logit estimate General Social Survey 1.20 (0.91-1.48) 1.26 (0.96-1.55) World Values Survey 1.25 (1.05-1.45) 1.26 (1.06-1.46) European Social Survey 1.34 (1.12-1.55) 1.25 (1.02-1.49) European Quality of Life Survey 1.19 (0.87-1.52) 1.05 (0.71-1.38) German Socio-Economic Panel 1.26 (0.90-1.63) 1.15 (0.81-1.49) British Household Panel Survey 1.30 (0.97-1.62) 1.32 (0.99-1.65) Combined estimate 1.26 (1.16-1.37) 1.23 (1.12-1.34) And the answer is that it falls well within the 95% confidence interval of all the individual surveys. Thus, unlike the case with choice under uncertainty, we find that estimates of ρ based on happiness surveys yield a single estimate that is consistent with very different data sets.

Table 5: Maximum likelihood estimate of p in different subgroups (using a standard linear dependent variable model and with 95% confidence intervals in parentheses). Sub-group ML estimate Men 1.22 (1.06-1.39) Women 1.26 (1.11-1.40) Age 30-42 1.27 (1.12-1.42) Age 43-55 1.26 (1.10-1.41) Low education 1.13 (0.85-1.40) Mid education 1.21 (1.01-1.42) High education 1.26 (1.16-1.37) Couples 1.27 (1.11-1.43) Singles (never married) 1.44 (1.13-1.77) Widowed/Separated/Divorced 1.34 (0.85-1.83) All subjects 1.26 (1.16-1.37)

Non-linearity of the h-u relationship

• Our results indicate that, under the assumption that h=u, the estimate of ρ is 1.26.

• This will be an over-estimate if and f’>0, f’’<0, because true utility is then a convex function of reported utility. So, true utility will be a less concave function of income than reported utility.

( )i ih f u

Non-linearity of the h-u relationship

• Indeed, in theory this effect could be so large that true utility could even be convex in income.

• How can we investigate the curvature of f ?

• We focus on the equation

1 1( )

1i

i i i

yh f z

other variables. Note additive function is maintained assumption.iz

The shape of ƒ(u), I

• We use three methods.

(i) Ordered Logit. The ordered logit estimate of ρ is 1.23. The cut points are slightly curved, consistent with

slight curvature of ƒ.

This method relies on the assumption that ε has a symmetric distribution.

-6-4

-20

2

0 2 4 6 8 10

Ordered logit cut points

0.5

11.

52

RM

SE

2 4 6 8 10Mean predicted reported happiness for person

Source: German Socio-Economic Panel.

RMS prediction error as function of predictions2

46

810

12Tr

ue u

tility

0 2 4 6 8 10Reported happiness

Source: German Socio-Economic Panel.

Estimated function linking true utility to happiness reports

.81

1.2

1.4

RM

SE

4 6 8 10 12Mean predicted true utility for person

Source: German Socio-Economic Panel.

RMS prediction error as function of predictions

Fig. 4: Evidence for the concavity of h = f(u) using the German Socio-Economic panel. (i) The top left panel

The shape of ƒ(u), II

(ii) Variance of the Residuals.

Assume true utility, u, has a scale with a constant standard error for test-retest mistakes. Reported happiness, һ, has variable units proportional to measured standard errors based on repeated observations on same person in GSOEP.

The shape of ƒ(u), III

•

• Estimate

• Subst. (2) into (1) and integrate

Plotted in bottom left panel in Fig. 4.

• Use this to correct ρ. After correction, ρ = 1.24.

(1)( ) / o

dhdu

h

log(1 ( ))oo

c h hu u

c

( )1 ( ) (2)o

o

hc h h

The shape of ƒ(u), IV

(iii) The Spline Test.

If ƒ is concave, if we combine the regressors into a single prediction variable, , by running a linear regression and then run separate regressions of reported happiness on the prediction variable in each half of the sample, the slope should be higher for low values of than for high values of

This can be used to compute a measure of the curvature of ƒ.

The corrected measure of ρ is 1.25.

h

h .h

Conclusions

1. We have estimated the elasticity of marginal utility of income with respect to income (ρ) based on measure of experienced utility.

2. We have used six different surveys.

3. We have attempted to investigate the extent to which the results are distorted because reported happiness is non-linear function of true utility.

4. Under our assumptions, ρ is around 1.24.

![[tr]Kullanma kιlavuzuLamba ve cihaz şalterlerini kullanmayınız, hiçbir fişi prizden çekmeyiniz. Evde telefon veya cep telefonu kullanmayınız. Pencereyi açınız ve odayı](https://static.fdocument.org/doc/165x107/604980e5c8c93e6082511cb4/trkullanma-klavuzu-lamba-ve-cihaz-alterlerini-kullanmaynz-hibir-fii.jpg)