Phonetic Change in Medieval Greek

-

Upload

davo-lo-schiavo -

Category

Documents

-

view

57 -

download

2

Transcript of Phonetic Change in Medieval Greek

PHONETIC CHANGE IN MEDIEVAL GREEK: FOCUS ON LIQUID INTERCHANGE * anolessou & Notis Toufexis University of Patras, University of Cambridge [email protected], [email protected]

Abstract The present paper aims to propose a methodology for the research of phonetic change in Medieval Greek, and to show, through the investigation of the phenomenon of liquid interchange, that a) the new electronic tools available for the study of Greek can contribute crucially to the research on the distribution of phonetic changes and b) phonetic changes in Medieval Greek are to a large extent regular and conform to cross-linguistic patterns.

1. Introduction Medieval Greek presents no major regular changes, i.e. conditioned changes of the Neogrammarian type, which apply without exceptions (or with explicable exceptions) in all the potential phonetic environments. Thus, whereas the student of the history of Ancient Greek meets with a standard list of regular phonetic changes with precisely describable conditions, which led from Indo-European to Greek or from Proto-Greek to the various Ancient Greek dialects (e.g. /a:/ > /:/ in Ionic and Attic) 1 and even from Attic Greek to the Koine, the phonetic rules of Medieval Greek never seem to apply across the board, resulting in considerable variation both in the texts of the period (Manolessou 2008) and Modern Greek (and its dialects). The reaction of scholars to this issue has up to now been one of hopeful procrastination: to postpone discussion pending a better knowledge of a) Medieval Greek texts and b) Modern Greek dialects. Now it is true that studies of MG dialectology are lagging behind in comparison with those in other countries. However, this is mainly true of theoretical/ structural descriptions of dialects (their phonology, morphology, syntax etc.) 2 . It is not true of dialectal vocabularies, as there exist hundreds of (amateur or not) local glossaries, and a wealth of dialectal attestations for each lexeme of Modern Greek collected in the archives of the Academy of Athens, dated

*

This paper is the outcome of research conducted for the project Grammar of Medieval Greek at the University of Cambridge, funded by a grant from the Arts & Humanities Research Council. For more information see http://www.mml.cam.ac.uk/greek/grammarofmedievalgreek . 1 These changes are described in standard historical grammars of Ancient Greek, e.g. Rix (1992). 2 For a recent overview of theoretical approaches to Modern Greek dialects, see Ralli (2006).

291

and geographically localised 3 . The situation nowadays, therefore, is quite different from the time when the first descriptions of Medieval Greek phonology were written (on which the descriptions of modern handbooks are based cf. the overview of desiderata in Mirambel 1953): it is now possible to track the spread of any phonetic change lexeme by lexeme in the Modern Greek dialects. Roughly the same observation can be made concerning our knowledge of Medieval Greek texts: a very large amount of published texts, both literary and non-literary, not available to earlier scholars is now easily accessible. We also possess better linguistic descriptions of Medieval Greek in general or of specific texts in particular, better tools for textual searches (such as electronic searchable texts, concordances, databases etc.) 4 , all of which were not at hand for those who first tackled the vagaries of Medieval Greek phonology. It is now possible therefore, as it was not before, to examine the spread and distribution of each phonetic change in all major and hundreds of minor medieval texts, from different areas and different periods 5 . Nevertheless, despite the considerable improvement in the available data, the current linguistic scholarship on Greek contains little discussion of specific phonetic changes in Medieval Greek. One reason for this apparent lack might be the fact that the better knowledge of Medieval Greek texts and MG dialects has not brought about the better understanding of the precise (phonetic) conditions/environments of application of a phonetic change (for example, why and but not *; why and but not *; 6 ) that researchers had hoped for. Thus, thorough examination of large amounts of medieval material by the Cambridge Grammar of Medieval Greek has shown that: a) no matter how vernacular a text, from whatever period or area, medieval sound changes are almost never attested with complete normality, i.e. without exceptions. For example, Dig. G III.69 but Dig. G IV.465 ; Chron.Mor. H 6646 but Chron.Mor. H 633; chill.O 279 but chill.O 551; Liv.V 2443 but Liv.V 1429. There is always variation, sometimes more, sometimes less. b) most inherited words which in Standard Modern Greek exist in unchanged form may appear in MedG with the change. For example, the following are all MedG attestations of the

On the contents of the Archives of the Center for Modern Greek Dialects of the Academy of Athens, see Manolessou, Karantzi & Yakoumaki (2004), and on its electronic availability see Academy of Athens (2001) and the website www.academyofathens.gr/ilne (accessed 12/03/2008). An electronic bibliography of local dialectal glossaries is available from the , at http://www.greek-language.gr/greekLang/medieval_greek/bibliographies/idiomatic/contents.html (accessed 12/03/2008). 4 On electronic corpora in historical Greek dialectology, see Manolessou & Toufexis (forthcoming), on available electronic resources in the field of Medieval Greek see Toufexis (forthcoming). 5 With all the caveats, of course, concerning the reliability of written sources of past periods, and especially Medieval Greek, for the representation of authentic linguistic usage (Manolessou 2008). 6 On this specific change (/i/ > /u/ adjacent to labial and velar consonants and s) see Joseph (1979), Moysiadis (2005: 97-103-105) and references therein.

3

292

change e > i adjacent to liquids and nasals, which do not appear so in MG: (1473, Corfu, KONIDARI & RODOLAKIS 1996: 78, 186.3); (1073, Miletos, VRANOUSI 1980: 50, 9.105); (1148, Calabria, GUILLOU 1963: 7, 82.17); (1112, Sicily, CUSA 1868/82: XIV, 410.17); Poulol. 540 app. cr. (); (1581, Andros, POLEMIS 1995: 26, 165.19); MACH., Chron. 81.12 (Pieris/Nikolaou-Konnari); Chron. Toc. 703; Diig. Alex. E 233.3 (Lolos). c) almost any inherited word which in Modern Greek has undergone the change may appear in Medieval Greek without it, even in very vernacular texts: For example, the following are attestations of forms which in MG have undergone synizesis (which dates probably around the 13th c. (Minas 1983: 289)), but which appear in Early Modern Greek texts in unchanged form, although the word itself (and the text from which it is taken) is vernacular: (1635, Nisyros, TSIRPANLIS 1982: 1, 13.3); BERG., Apok. V 27; NOUK., Aisop. Myth. 28.2; (1500, Crete, MAVROMATIS 1994: 1 [], 237.15); , , , , , (1642, Patmos, MICHAILARIS 1998: 1, 193.12). d) there is a vast amount of hypercorrection going on, which means i) that frequently the change is attested only indirectly, through changes in etymologically unjustifiable words, something which makes both electronic and traditional searches for attestations of the spread of the phenomenon very difficult and ii) that the tendency to correct and hide the change in written language is very strong. For example, the following are attestations of hypercorrection of the Northern dialect phenomenon of mid-vowel raising: (1445, Macedonia, BOMPAIRE 1964: 30, 217.30); (post 1356?, Epirus, ALEXOULIS 1892: 1, 277.7); (1618, Serres, ODORICO 1998: 33, 114.3); (1695, Kastoria, MERTZIOS 1947: 2, 212.4). The cause of the variation and of the non-regularity of MedG phonetic change is not that we do not understand the environments, the conditions, and the working of the changes, or that we do not have more precisely geographically and chronologically located information on the spread of the changes. Also, it is not that they are by nature sporadic changes (like metathesis or vowel assimilation). On the contrary, many of them are perfectly regular neogrammarian sound changes, which predictable environments and exceptions (analogical levellings, hypercorrections, posterior loans). Its just that they were arrested in progress. Medieval (and Modern) Greek is an ideal exemplification and documentation of spread of sound change by lexical diffusion. In some areas, in some periods, in some registers, more words are affected than in others. Ultimately, the period of activity of the change is over, before it has covered the totality of the vocabulary. The parallel existence of a learned language as a model could be seen as the ultimate inhibiting factor. Frequently it can be shown that the period of activity of a

293

phonetic change is several hundred years, or that in fact it is still active in Modern Greek, and still being counteracted by the standard language. This of course does not entail that it is fruitless to investigate MedG source texts from the point of view of phonology. First of all, we do need the data in order to rule out the possibility that the conditioning factor is indeed a specific phonetic environment. Secondly, we need up to date descriptions of changes, couched in modern terms, so as to be comparable with the results of research on other languages and to contribute to linguistic theory on phonetic change. And thirdly, we need to have an accurate picture of the various phonetic changes in Medieval Greek not only for use in comparative historical linguistics, but also in sociolinguistics, and textual edition and interpretation. 2. A case study: liquid interchange In order to exemplify concretely the claims made above concerning a) the feasibility and utility of research on and b) the interpretation of the regularity (or non-regularity) of phonetic change in Medieval Greek, in what follows, we will investigate a specific sound change, the so-called liquid interchange, which in fact consists of two different sub-changes: a) b) change of /l/ > /r/ when it is the first member of a consonant cluster (classic examples: > , > ) and change of /r/ > /l/ when another /r/ sound follows in the same word (classic examples: > , > ). We aim to provide as much detail as possible, i.e. by examining all lexemes of the Greek language possessing the appropriate phonetic environments, and checking from both written and oral sources (medieval documents and dialectal data) whether they are attested in changed form or not. The first to have noted and described the phenomenon of liquid interchange is Simon Portius in his grammar of 1638 (Meyer 1889: 10). The phenomenon is of course well-known in the literature on the history of Greek and its dialects, but there are in fact only one and-ahalf article dedicated to it: a detailed setting out of the data by J. Psichari (1905/1930), collecting most known (at the time) instances of the phenomenon from Ancient, Medieval and Modern Greek, and a short attempt at interpretation by G. Shipp (1958), linking it with other dissimilatory phenomena in Greek phonology. We are still lacking, therefore, a modern account which will incorporate a) cross-linguistic data and theoretical phonological accounts and b) the new wealth of information available through the progress of research on Greek and its dialects, as well as the new electronic research tools.

294

2.1. Cross-linguistic and theoretical documentation Concerning the first point, both sub-phenomena of liquid interchange, i.e. dissimilation of consecutive liquids and liquid variation in front of consonants, are well-attested in many languages. The behaviour of Greek, therefore, has to be compared with similar crosslinguistic attestations and the interpretations proposed for them. In detail: The most well-known case of liquid dissimilation is that of Latin, in which the derivational suffix -/alis/ appears as -/aris/ when the stem of the word contains another /l/ (Steriade 1987, Odden 1994 among others): navis nav-alis, natura natur-alis, sol sol-aris, linea line-aris A similar case of dissimilation in specific suffixes occurs in Georgian (Fallon 1993), where the derivational suffix -/uri/, forming ethnic adjectives, appears as -/uli/ when the stem contains another /r/: dan-uri Danish, polon-uri Polish, ungr-uli Hungarian, aprik-uli African Yet a third documented case is the West Indonesian language of the Sunda islands (Sundanese), in which the plural infix -/ar/ appears as -/al/ when the root contains another /r/ (Cohn 1992, Holton 1995): kusut k-ar-usut messy, dama d-ar-ama well, hormat h-al-ormat respect, combrek c-al-ombrek cold All of these phenomena are in fact grammaticalised dissimilations, in that they require grammatical, i.e. morphological information, since they concern specific affixes. The Greek case is somewhat different: it affects consecutive /r/ sounds in the root of words, and does not seem to occur in suffixes or in composition (see below for a more detailed description of the data). A greater similarity to the Greek phenomenon is observable in the sporadic dissimilation of consecutive /r/ sounds in several Romance languages such as Spanish, Catalan, Portuguese and Italian (Lloret 1997, Colantoni & Steele 2005): Lat. cerebrum > Sp. celebro brain, Lat. peregrinum > It. pelegrino pilgrim, Lat. armarium > Port. almario cupboard, Lat. aratrum > W. Cat. aladre plough. A few Romance dissimilated words have also made it into English as loanwords, such as marble ( veldad, Lat. carta > Sp. carta > calta, Lat. populum > pueblo > puebro, Bermudez (pr. name) > Belmudez, Lat. palma > Sard. parma > prama, Lat. plus > Sard. prus, Lat. flamma > Sard. framma. The diachrony of the Romance languages shows a frequent phenomenon of liquid interchange in consonant clusters, which may or may not have survived in the modern standard language. From a theoretical phonological point of view this phenomenon is interpreted as a neutralization of the distinctive feature which distinguishes rhotics from laterals in specific positions (the phenomenon is technically termed positional neutralization of liquids, Rice 2005). The choice of the surfacing liquid (/r/ or /l/) seems to be languagespecific, and connected with the notion of markedness: in each phonological system, one of the liquids is the unmarked one (the most frequent, with the wider phonotactic distribution) and this is the one that is preferred in consonant cluster alternations a result known as emergence of the unmarked in theoretical phonology. This does not exclude the possibility of the reverse change also occurring in the language, but in this case it should perhaps be interpreted as a hypercorrection. In the Greek case, the unmarked consonant seems to be /r/, as there are far more clusters with /r/ + consonant than with /l/ + consonant. This can be (imperfectly) demonstrated by a search in the electronic

296

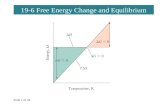

version of the of the Triantafyllidis foundation 7 , through comparing the number of words containing the two types of consonant clusters:Table 1. Frequency of liquid consonant clusters in Standard Modern Greek v z k l m n ks p r s t f x ps Total /r/ + consonant 114 631 264 9 171 272 84 620 363 18 140 0 122 681 216 448 4 4157 /l/ + consonant 36 47 7 4 10 119 0 128 25 3 70 0 20 182 69 6 2 728

It seems again, therefore, that Greek can be brought into line with several other languages presenting similar phenomena, and that such comparative research can shed light on the causality of the change. It furthermore seems that liquid alternations in consonant clusters also possess the potential to become a regular, exceptionless sound change. 2.2 Historical overview Let us now turn to the detailed examination of the two liquid interchange phenomena in the history of Greek. 2.2.1 Classical and Koine Greek here are no attestations of the consonant cluster interchange in Classical literature. The first, and quite rare, attestations of the phenomenon appear in Attic inscriptions, all of which are quite late, dated to the Roman period. Examples are collected in Dieterich (1898: 107), Jannaris (1898: 187), Meisterhans-Schwyzer (19003: 83), Lademann (1915: 119), Schwyzer (1939: 213) and Psichari (1905/1930). Some of these, however, are misreadings of earlier scholars or refer to outdated editions; the most reliable information comes from Threatte (1994: 483):

See http://www.greek-language.gr/greekLang/moderngreek/tools/lexica/triantafyllides/index.html (accessed 12/03/2008). We are fully aware of the methodological constraints of using only one electronically available lexical database; the data presented here can without doubt be enriched with the help of other electronic or traditional resources.

7

297

IG II22242.33, 238/9 AD (< Calpurnius), IG II2 2245.222, 262/3 AD, IG II2 13224.6, 3rd c. AD (< ), gora inv. no. IL 493.27, 3rd c. AD, G III 3531 (early Christian).Interchange in consonant clusters occurs in the papyri of the Roman and Byzantine periods (examples from Gignac 1976: 105): PRyl. 160c, i.7,16 (AD 32), PMich.204.5 (AD 7), POxy 1059 (6th AD). However, liquid interchange in the late Egyptian papyri is more frequent than in any other written documents of any period of Greek, and furthermore it happens also unconditionally, i.e. even outside consonant clusters: , (Pryl 160c, i.10 (AD 32), PMich.310.16 (27 AD), SB 5110 (AD 42). Gignac (1976: 106-7) claims that this frequent interchange of and indicates that there was only one liquid phoneme /l/ in the speech of many writers in the Roman and Byzantine periods. In the literature of this era we also find one or two examples of the dissimilatory change, namely the frequently occurring (< Lat. flagellum) in the NT (Ev. Jh 2.15, Matth. 27.26) and nce (Act. Apost. 27.30 (Sin.)). Summing up this period: both changes begin to appear around the 2nd 3rd c. AD, with isolated exceptions such as which do not constitute prototypical instantiations of the phenomena. It cannot be claimed that the changes possess any regularity, with the possible exception of Egyptian Greek, where there is substratum interference. 2.2.2 Medieval Greek oth phenomena are attested in Medieval Greek, starting from the sporadic attestations of the early Byzantine period collected by Psaltes (1913: 76, 98), e.g. DAI 75.11. /l/ > /r/ in consonant clusters An electronic search of the corpus of Christian Inscriptions (PHI#6 CD-ROM) has shown that a few specific words appear frequently in changed form, therefore the change seems to have been stabilized, for these words at least. For example, the word and its derivatives appears 16 times, the word and its derivatives appears 14 times: TAM II 1142; MAMA 4 195; IK Iznik 576; Corinth 8,1 207; SEG 37:1292; IScM III 194; MAMA 3 514.

298

A search of all /l/ + consonant combinations in the electronic version of Kriaras (1967-) (only up to the lemma ) 8 , plus all data collected by the Medieval Greek Grammar project has given a small corpus of 290 words which potentially could undergo the change. Of these 76 are attested in Medieval Greek as actually having undergone it (percentage 26 %): , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , /, /, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , /, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , . An important note that should be made is that the /l/ > /r/ change is an active change in Medieval Greek, as it has affected not only forms inherited from previous periods, but also medieval loanwords (such as , , , , ). The examination of the words that have not undergone the change shows that they are mostly learned words, such as: , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , . Also some of them are hapax words in the medieval literature, such as: , , ,

.

8

Available under http://www.greek-language.gr/greekLang/medieval_greek/kriaras/index.html (accessed 12/03/2007).

299

There are a number of words which seem to have undergone the reverse change, i.e. changing a /r/ + consonant cluster to a /l/ + consonant cluster: , , , , , , , , , , , , B, , , , , , . These constitute less than 1% of the total words which could potentially undergo the change, i.e. the medieval words which contain a cluster of /r/ + consonant. Furthermore, for some of them alternative causes can be brought forward: for example, the /l/ in (< it. arbitro < lat. arbiter) and its family of words could be attributed to dissimilation with the following second /r/ in the word, or could have been borrowed already containing the /lb/ cluster, as this form is attested in Italian dialects such as Venetian. In this connection it should be noted that most of these words are of foreign origin ( < burrichus, < burgensis, < purgatorium, < veretone). Note also the proper name Bo in the Alexiad < Burkhard (3.10.4.13, ed. Leib). Interestingly, Portius already had noted that it is foreign words which tend to change /r/ to /l/ in consonant clusters, giving the example of < scrima (Meyer 1889: 10). On the basis of the above, therefore, it can be claimed that the reverse /r/ > /l/ change is not a regular phenomenon of Greek, but a hypercorrection or an imitation of Romance models. he medieval data can be complemented through the evidence of MG dialects, from which a further 22 words presenting the change /l/ > /r/ can be added to the above, bringing the total to 98 (percentage 34 %): , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , . Dissimilation Turning now to the second phenomenon, that of the dissimilation of consecutive rhotic sounds, even a cursory examination shows that it is much less widespread than the first. Thus, of a total of 831 words (in Kriaras Lex. and the data collected by the Medieval Grammar project) that could potentially undergo the change, only 30 of them do, again either in MedG source texts or in MG dialects (percentage 3,61 %):

300

, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , /l/ or /l/ to /r/ change in that the liquid constitutes the second member of the cluster, or there is no second liquid in the word. Examples include , . As far as the distribution in Medieval source texts is concerned, it can be stated that there are no sources where the change appears with complete regularity, meaning both that a) the same lexical item may appear in the same text in both the changed and unchanged form and b) different lexical items, both presenting the proper phonological environment for the change behave differently in the same document, one presenting the change and one not. Interestingly, the same picture is presented by Spanish documents of the same period, exhibiting the same phenomenon of liquid interchange (Fontanella de Weinberg 1984). To give one characteristic example, the notary and professional scribe uses in the 154 wills (dated 1506-1532) that are available to us today (ed. Mavromatis / Lambakis 2003) always only the unaltered from of his surname (-); the altered form - appears in these documents only twice: once in the signature of a witness (no. 2 , p. 6) and once in a written instruction of the duke of Candia to himself ( | ..., p. 65). It is obvious that while the sound change was operating in Crete at the time this notary was writing, he chose not to represent it in the written records he is producing. The key factor which seems to increase or decrease the percentage of changed items is register. Thus, again, documents from Cyprus, which are in a more decidedly dialectal character, present both greater regularity in same words, and a wider variety of words which show the change some of the words in the lists provided above are attested only in Cypriot documents (e.g. , ).

301

2.2.3 Modern Greek An electronic search of the /l/ + consonant clusters in the Triantaphyllidis dictionary has given a total of 460 words which could potentially undergo the change. Of these, only 19 words appear in changed form in Standard Modern Greek: , , , , , , , , , , , , , /, , , , , . However, if one turns to the MG dialects, and more specifically to the dialectal archives of the Academy of Athens, an impressive additional 130 words are found, bringing the percentage of SMG words presenting the phenomenon from to 32%, similar to the levels of Medieval Greek: , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , /, ( , > , > ) which would make the total considerably higher. The words that have not undergone the change are almost always either learned new creations or recent loanwords:

302

, , , , , , , , , , , , , etc. On the basis of the above it is possible to conclude that the change is regular in MG, as well, leaving unaffected only the words belonging to higher registers. It must be noted that the change is still active in the dialects, because even comparatively recent loanwords have undergone it, including: revolver > > (Corfu), (Eub., Chios), (Cephall.), (Pont.), (Peloponn.), (Ionia), waltz > > (Naxos), bolshevik > > (Karpathos). Although the sampling of the dialectal material available in the Academy of Athens is unequal (i.e. some areas are overrepresented), it is apparent from the distribution of the changed forms that the phenomenon is stronger in southern dialects, such as Cycladic, Cretan and Dodecanesian. As far as the second change is concerned, that of dissimilation of /r/ to /l/ in the presence of a second rhotic, the data are again similar to the medieval ones. That is, the number of words that could potentially undergo the change, as they contain two /r/s, is very high, about 3400. However, in standard MG less than 10 words appear in changed form, a percentage of less than 0,2 %: , , (marginal), , , , The MG dialects add to this meager number an additional 20 words, which might increase if we investigate dialectal material more thoroughly: (< erba rosa, ), , , , , , , , , (< ), (< ), (< ), < , < renper, < , < , , , , . Again, the presence of comparatively recent lexical items which have undergone the change (e.g. ) shows that the change is still active in MG. As far as one can tell from the examination of the items which have not undergone the change, the limitation to non-learned high register vocabulary is not sufficient here. The change is not apparent also in the following contexts:

303

a) when the word is a compound. For example, none of the hundreds of compounds in -, -, -, - displays the change. he Greek phenomenon operates in a different way from the grammaticalised suffix interchanges seen in other languages. b) when the change would create a consonant cluster disallowed or dispreferred by the phonotactics of Greek, e.g. > *, > ? 3. Conclusions We have investigated two different sound changes in the diachrony of Greek. Both of them involve liquids, the first in consonant clusters and the second in dissimilatory contexts. It has been shown that the detailed examination of the data, with the help of electronic research tools, can help us draw clearer conclusions as to the behaviour of sound changes in Greek: both changes are active for a very extensive period of time (about 2000 years), something that requires explanation. Also, they are both cross-linguistically well-attested changes which can be explained on the basis of known phonological processes. However, in their distribution they are widely dissimilar: while the first change is a potentially regular change, spreading to about one third of the vocabulary of any given period, and arrested primarily in lexical items of higher registers, the second change is a sporadic one, affecting less than 1% of the vocabulary. We hope to have shown that a) the specific change investigated here can provide a useful case study for research on the diffusion of sound change in general and b) the methodology followed for the present research can, and should, be applied to all other sound changes affecting Medieval and Modern Greek. ReferencesAcademy of Athens, (1933-). , . Athens. cademy of Athens, (2001). 23 - . Achil. O = Smith O. L., (1990). The Oxford Version of the ACHILLEID [Opuscula graecolatina, 32], Copenhagen. Alexoulis, A., (1892). , 4 (1892) 275-281. Apok. V = Vejleskov P., (2005). APOKOPOS. A fifteenth century Greek (Veneto-Cretan) catabasis in the vernacular. Synoptic edition with an introduction, commentary and Index verborum, Cologne: Romiosini. Bompaire J., (1964). Actes de Xropotamou. dition diplomatique, Paris. Chron. Mor. = Schmitt J., (1904). The Chronicle of Morea, . A History in Political Verse [...], London 1904, repr. Groningen 1967, Athens 2003 Chron. Toc. = Schir G., (1975). Cronaca dei Tocco di Cefalonia di anonimo: prolegomeni, testo critico e traduzione, a cura di G. Schir, Rome 1975. Cohn A., (1992). The Consequences of Dissimilation in Sundanese. Phonology 9, 199-220. Colantoni L. & J. Steele (2005). Liquid asymmetries in French and Spanish. Toronto Working Papers in Linguistics 24, 1-14. Cusa S., (1868/82). I diplomi greci ed arabi di Sicilia, Palermo vol. 1. part 1, 1868, vol. 1. part 2, 1882, repr. Cologne Vienna: Bhlau 1982. Dieterich K., (1898). Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der griechischen Sprache von den hellenistischen Zeit bis zum 10. Jahrh. n.Chr. Leipzig: Teubner. Dig. G = Jeffreys . ., (1998). Digenis Akritis. The Grottaferrata and Escorial Versions, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1998.

304

Diig. Alex. E = Lolos A. C., (1983). Ps.-Kallisthenes: Zwei mittelgriechische Prosa-Fassungen des Alexanderromans, Teil I, Knigstein 1983. Fallon P., (1993). Liquid Dissimilation in Georgian. Proceedings of the Tenth Eastern States Conference on Linguistics (ESCOL 93), ed. by Andreas Kathol and Michael Bernstein, 105-116. Fontanella de Weinberg, M. B., (1984). Confusin de lquidas en el espaol rioplatense (siglos XVI a XVIII). Romance Philology 37, 432-45. Frigeni, Ch., (2005). The development of liquids from Latin to Campidanian Sardinian: The role of contrast and structural similarity. Toronto Working Papers in Linguistics 24, 1530 Gignac, F. T., (1976). A Grammar of the Greek papyri of the Roman and Byzantine Periods. Vol. I, Phonology. Milano: Cisalpino-Goliardica. Guillou A., (1963). Les actes grecs de S. Maria di Messina. Enqute sur les actes grecs dItalie du sud et de Sicile (XI e-XIV e s.), Palermo 1963. Holton, D., (1995). Assimilation and Dissimilation of Sundanese Liquids. In J. Beckman, L. Dickey and S. Urbanczyk (eds.), Papers in Optimality Theory: University of Massachusetts Occasional Papers 18, 167- 180. Jannaris, A.N., (1897). An historical Greek Grammar chiefly of the Attic dialect as written and spoken from classical antiquity down to the present time, founded upon the ancient texts, inscriptions, papyri and present popular Greek. London/ NY: MacMillan. Joseph B. D., (1979): Irregular [u] in Greek. Die Sprache 25, 46-8. Karaboula D.P. & L. Paparriga-Artemiadi, (1998). (1513-1516), 34 (1998) 9-126. Konidari I. M. & G. Rodolakis, (1996). (1472-1473), 32 (1996), 139-205. Lademann, W., (1915). De titulis atticis questiones orthographicae et grammaticae. Kirchhain: Schmersow. Lemerle P., (1945/46). Actes de Kutlumus. d. diplomatique, Paris, 1945-46. Liv. V = Lendari T., (2007). (Livistros and Rodamne). The Vatican Version. Critical edition with Introduction, Commentary and Index-Glossary. Editio princeps, Athens: MIET 2007. Lloret, M. R., (1997). Sonorant dissimilation in the Iberian languages. In F. Martnez-Gil & A. Morales Front (eds.), Issues in the phonology and morphology of the major Iberian languages, Washington D. C.: Georgetown University Press, 127-50. Mach., Chron. O = Pieris M., Nikolaou-Konnari A., (2003). , . , Nicosia 2003. Manolessou, I., (2008). On historical linguistics, linguistic variation and Medieval Greek. Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 32, 63-79. Manolessou I., Ch. Karantzi & E. Yakoumaki, (2004). ( ) . In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of Greek Linguistics (ICGL 6) Rethymnon [available online, accessed 12/03/2008: http://www.philology.uoc.gr/conferences/6thICGL/ebook/a%5Cmanolessou&giakoumaki&karantzi .pdf] Manolessou, I. & N. Toufexis, (forthcoming). Corpus linguistics and historical dialectology. A case study of Cypriot. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Modern Greek dialects and Linguistic Theory, Nicosia, 14-16 June 2007. Mavromatis, G., (1994). , . (1496-1543), Venice 1994. Mavromatis, G. & St. Lambakis, (2003). , 1506-1533: , , , Herakleion. Meisterhans, K. & E. Schwyzer, (19003). Grammatik der attischen Inschriften. Berlin: Weidmann. Mertzios K. D., (1947). (1695-1699), [ , 7], Thessaloniki 1947, 209-264 Meyer, W., (ed.) (1889). Simon Portius, Grammatica Linguae Grecae Vulgaris, 1638. Paris: Vieweg. Michailaris, P., (1976). (1695-1696) . . . . , 13 (1976), 245-257. Minas, K., (1983). e/, i/ . 12 (1983) 283-9. Mirambel, A., (1953). Essai de phonologie du grec byzantin. In Atti del VII congresso internazionale di studi bizantini 1951 (Studi bizantini e neoellenici), v.1, 303. Moysiadis, Th., (2005). . . Athens: Ellinika Grammata.

305

Nouk., Aisop. Myth. = Parasoglou, G. M., (1993) . . . . Athens: Ermis 1993. Odden, D., (1994). Adjacency Parameters in Phonology, Language 70, 289-330. Odorico, P., (1998). Le codex B du Monastre Saint-Jean-Prodrome (Serrs). B (XVe-XIXe sicles), Paris 1998. PHI#6 = Packard Humanities Institute CD-ROM 6. Also available online at http://epigraphy.packhum.org/inscriptions/ (accessed 12/03/2008). Polemis, D. I., (1995). . 16 ., Andros. Psaltes, S., (1913). Grammatik der byzantinischen Chroniken. Gttingen: Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht. Psichari, J., (1905/1930). Essais de grammaire historique: Le changement de l en r devant consonnes en grec ancien, mdieval et moderne. In Psichari J., Quelques travaux de linguistique, de philologie et de littrature hellniques, 1884-1928. Paris : Belles Lettres, 664-710. [= Memoires Orientaux, Congrs de 1905, Paris 1905, 231-36]. Poulol. = Tsavari, ., (1987). O . K , , thens 1987. Ralli, A., (2006). Syntactic and morphosyntactic phenomena in Modern Greek dialects. The state of the art. Journal of Greek Linguistics 7, 121-159. Rice, K., (2005). Liquid relationships. Toronto Working Papers in Linguistics 24, 3144. Rix, H., (19922). Historische Grammatik des Griechischen. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. Sadler, J. D., (1973). Assimilation and Dissimilation, The Classical Journal, 68, 267-271. Schwyzer E. (1956). Griechische Grammatik. Mnchen: Beck. Shipp, G.P., (1958). The phonology of Modern Greek. Glotta 37, 233-58. Steriade, D., (1987). Redundant values. Chicago Linguistic Society 23, 339-62. Straka, G., (1979). Contribution la description et l'histoire des consonnes L. In G. Straka (ed.), Les sons et les mots, Paris: Klincksieck, 363-422. Suzuki, K., (1998). A typological investigation of dissimilation. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Arizona. Available at ROA. Threatte, L., (1994). The Grammar of Attic Inscriptions. Vol. I, Phonology. Berlin: De Gruyter. Toufexis, (forthocoming). Creating a database for the Grammar of Medieval Greek project. In I. Mavromatis (ed.), Proceedings of the International Conference Neograeca Medii Aevi, University of Ioannina, September 2005 Tsirpanlis, Z.N., (1982). (17-19 .). , 8 (1982), 7-21. Vranousi, E.L., (1980). . . 1: , Athens 1980.

306