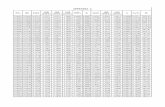

Chapter 10 TABLE

description

Transcript of Chapter 10 TABLE

-

A Mathematician's Take on FM

Part I

Interest Theory (65 80%)1 Interest Rates and Time Value of Money

1. Easy formulas (most of these are denitions/easy to derive):

d =i

1 + i,

v =1

1 + i,

v + d = 1,

i d = id,

d = iv,

and

d < d(m) < < i(m) < i.

2. When given nominal rates, instead of calculating the eective interest rate using ICONV and then calculate (1 + i)n

where n is the number of years, it is much much easier to use the nominal rate directly, i.e.,(

1 + i(m)

m

)nmor(

1 d(m)m)nm.

3. It is important to understand these three formulas,

1 + i =

(1 +

i(m)

m

)m,

1 d =(

1 d(m)

m

)m,

and (1 +

i(m)

m

)m=

(1 d

(m)

m

)m.

Use intuition, not brute force.

4. Continuous interest: = ln (1 + i). 5% compounded continuously means = 0.05, not i = 0.05! Equivalently, we

can also understand it as a nominal rate of 5% convertible continuously/innitely. Formula to memorize:

a (t) = a (0) et. (1)

Here is always a constant, for example, 0.05 mentioned above. It is not to be confused with the instantaneous

force of interest below:

5. Force of interest: (t) = a(t)a(t) is a function of t, and

astart amount

eend time

start time

(u)du = aend amount

. (2)

-

Some a (t) are easy to get given (t), for example, when (t) = mt+n , a (t) = (t+ n)m. (m and n are positive

integers). Also, when a (t) is of the form (1), then (t) happens to be a constantso the previous bullet point is

really just a special case where the force of interest is always a number, for example, 0.05, it is basically a constant

function (of t).

-

2 Annuities

1. Make the best out of STO and RCL features! Trust me, this is the dierence maker! I am surprised that ACTEX

doesn't mention this at all. Practice with your calculator! You calculator is your best friend!

2. Make sure you know how to use the calculator to solve the CF-related questions.

3. Always remember to CLR TVM. CPT N if you are not sure if you did, if Error 1, then you are good to go. Or just

simply CLR TVM again. CLR TVM does not clear CF data, you need to CLR WORK within the CF interface to

do that.

4. For problems that do not have both present and future values involved, there is no need to worry about plus/minus

signs if you are not calculating the interest. When the payment is plus (minus), then the present value or future

value is minus (plus). Edit: after a while, especially after later chapters, it becomes a second nature to get the signs

right, so I guess it does not hurt to train yourself early.

5. Check if it's beginning or end on calculator. Default is end (does not show BGN). My friend, who is an accountant,

said that I should never bother switching between beginning and end, just do everything as if it is end, then multiply

the result by (1 + i) if it is beginning.

anq =1 vni(3)

3 is all you need to memorize for level payments, here is why

Immediate = end = denominator is i = normal: 3.

Due = beginning = denominator is d = two dots: anq = 1vn

d .

Continuous = denominator = bar: anq = 1vn

.

Again, given the same amount of payment, then the present value of due = (1 + i) present value of immediate,

because x =(

x1+i

)(1 + i), think about it.

6. For future values, just multiply dierent versions of 3 by (1 + i)naccordingly.

7. All you need for arithmetic payment problems is this all-inclusive formula:

Panq +Q(anq nvn

i

).

Write it down on scrap paper at the beginning of the exam.

1

Remember, when it is Ia, P = Q = 1, when it is Da,

P = n, Q = 1. When Q 6= 1, make sure you multiply the nvn term with Q too when you break the bracket.

8. We will show that it is intuitively easy to understand

1(

1+g1+i

)ni g . (4)

But you need to rst memorize the perpetuity formula (which is easy to memorize)

1

i g . (5)

Since 5 is positive and has i g at the bottom, we assume that i > g (actually when g > i, the perpetuity divergesand therefore the formula is meaningless). In order for the fraction part of the numerator of 4,

(1+g1+i

)n, to go

to zero when n goes to innity, its numerator should be smaller than the denominator, thus 1 + g is on top, and

1

See 11 for a complete short list of important formulas that you should write down at the beginning of the exam.

-

therefore, 1 + i is at the bottom. The power is n also makes sense because before the rst payment, i.e., when n = 0,

the numerator should zero, so it checks out.

9. Just to emphasize, 5 and etc. is for immediates, it calculates the present value of the total payments 1 period before

the rst payment. Also keep in mind that the nal result is

rst payment1

(1+g1+i

)ni g ,

where the rst payment could be of the form x (1 + g) already.

10. The future value of A at time t1 is twice the future value of B at time t2 does not mean the current value (present

value today) of A is twice the current value of B. It is extremely important that you are always crystal clear about

the time t when you talk about present values and/or future values.

11. ALWAYS distinguish between the interest rate and the actual interest value, do NOT confuse between K% and K,

the calculator uses 5 for 5%, make sure you use 0.05 when you do calculations!

12. If money is deposited constantly at c (t), and force of interest is (t) compounded continuously, then the nal amount

is end

begin

c (t) eend

t(u)dudt. (6)

6 is pretty complicated on the surface, yet it is actually a straight forward formula. It tests your understanding of

1 and 2 greatly. (Courtesy of question 8)

13. If you need x retirement income and you are told that every thousand in the fund will generate k each period, then

you need

xk1000 in the fund. (Courtesy of question 12)

14. Keep in mind that the end of the 10th year is the beginning of the 11th year. Don't just stop at the beginning of the

10th year! When you are drawing a cash ow chart, always go one extra year at the end, just in case. Also, keep in

mind that, on the time axis, n always indicates the end of the nth year, because you start with 0!

15. When a geometrically increasing payment decreases by the same percentage, you have to calculate the new payment

manually, for example, at 10% increase and decrease, we have 100, 110, 1100.9 = 99, not 100, 110, 100. In generalit is x (1 + i)

n, x (1 + i)

n+1, x (1 + i)

n+1(1 i), not x (1 + i)n, x (1 + i)n+1, x (1 + i)n! (Courtesy of question 24)

-

3 Loan Repayment

1. Loan payment at time k: Pk. Notation.

2. Balance after Pk is made: Bk. Notation.

3. Loan amount: B0. Obvious since 0 payment has been made.

4. Interest paid in Pk+1: Ik+1 = i (Bk). Your new payment always pays the interest of the old balance o rst. Key

concept!

5. Principal paid in Pk+1: Rk+1 = Pk+1 Ik+1. Obvious!

6. Balance after Pk+1 is made:

Bk+1 = Bk Rk+1 = Bk (1 + i) Pk+1 (7)

There are two ways to look at the balance after Pk+1 is made:

(a) Old balance subtract the new principal paid, this is straight forward.

(b) The second is a mathematical result, it is counter-intuitive but let us rst look at an example: say we borrow

10 today and we repay 1 year from now, we obviously need to repay 10 (1 + i). The new balance after our

repayment is 0 regardless if we calculate 10 10 (rst way) or 10 (1 + i) 10 (1 + i) (second way). The newbalance is the future value of the loan one period from now, so if we do not pay anything one period from now,

the new balance would simply be Bk (1 + i), but we are going to pay Pk+1, thus Bk (1 + i) Pk+1.

Some usual ways to understand equations involving indices n, k, etc.:

(a) Look at simple examples.

(b) Consider extreme cases like when the index is 0 or .

7. Prospective method: the loan balance after Pk is the present value of the rest payments at the time of Pk. If we

calculated the present value of all the future payments at the time we borrow the money, it would have to equal to

the loan amount, otherwise it's not a fair trade! So then it is simple: consider the new loan balance after payment

Pk a brand new loan that you borrow right after payment Pk!

8. Retrospective balance:

Bk = B0 (1 + i)k

k1

Pj (1 + i)kj

. (8)

ACTEX does a good job explaining this one: if we do not pay anything until payment Pk, then the loan would

grow to B0 (1 + i)k, so to calculate the balance after Pk, when we know that we in fact did make payments, we

would calculate the present value of all the payments at time when Pk is made, so at time k. The rst term of the

summation is P1 (1 + i)k1, because the rst payment grows to P1 (1 + i)

k1at time k. For example, when k = 2,

it would be P1 (1 + i)21

= P1 (1 + i), not P1 (1 + i)2! The last term of the summation is Pk (1 + i)

kk= Pk which

is obviously true, the current value (present value today) of $1 paid today is simply $1. If you accept this analogy,

then the second part of 7 also becomes intuitively true because it would simply be a special case.

9. For Level Payment x, the principal paid in payment t is:

xvnt+1. (9)

Remember, with each payment you make, you pay more and more principal. So clearly, there should be an (n t)somewhere in the power of v, now to remember the extra +1, you just have to realize that you NEVER make a

payment that is 100% principal, so if it was not there, you would be paying xvnn = x principal, so 100% principal,in the last payment.

-

10. For Level Payment x, the interest paid in payment t is: xxvnt+1 = x (1 vnt+1). You do not need to memorizethis one, it is trivial given 9!

11. For Level Payment x, the prospective balance at time k, xankq. Same as above, look at it this way: you have anew loan with n k payments of x left, what is the loan amount?

12. For Level Payment x, the retrospective balance is Bk = B0 (1 + i)k xskq. It is nothing but a special case of 8.

13. Sinking Fund Loan, Loan interest rate: i, Sinking fund deposit rate: j.

14. Sinking Fund Deposit: x = Lsnqj . Simple, because you want xsnqj = L. This can usually be done with a calculator.

15. Term interest payable to the lender: y = Li. Trivial.

16. Total sinking fund payment: z = x+ y = Lsnqj + Li = L(i+ 1snqj

). Trivial.

17. Balance in the fund after payment k: Bk = xskqj . Trivial, but notice that when k = n, you get L which is expected.

18. Principal paid in payment t is x (1 + j)t1

= xv1tj . This is similar to 9, except, there is no n. So memorize it bybrute force, keep in mind the v is based on j not i, because i is only related to the interest!

19. Net interest in payment t: z xv1tj . Obvious, you take the whole payment, subtract the principal (which wememorized by brute force), and you are left with the interest.

20. Another way to calculate net interest in payment t: yBt1j. This is actually easy to understand: y itself is 100%interest, but you make some interest back from your fund in this period too, the interest that you make is Bt1j, sosubtract and ta-da!

21. Do not confuse between the nth year and the nth payment! If the rst payment is made at time 0, then payment

n+ 1 is actually made at the spot where you write n in the time axis.

22. When it is monthly payment but the question asks in k years, make sure you input N as 12k, I made this silly

mistake!

23. Just to emphasize, the loan balance at the end of one year is the present value of all future payments at the end of

one year, not today! Again, present value does not necessarily mean today!

24. APR means annual percentage rate, it is the true interest rate. You calculate the payment with the original loan,

then CPT PMT, then change the original loan to the actual amount (usually something like original (1 2.5%)),CPT I/Y.

-

4 Bonds

1. A bond is basically a series of xed level payments (returns), to the investor x, called coupons, with a huge last

payment, x+R, coupon + redemption.

2. The price of a bond, P , is the present value of all of those

P = xanq +Rvn. (10)

3. r = xF is called the coupon rate, where F , xed, is called the face value, since x and F are both xed, r is xed too.

4. Sometimes the interest rate demanded by investors go up (or down), compared to the xed r, i.e., they will settle

with a higher (or lower) yield per period rate i, which is the interest rate used in 10. The only way to achieve those

while 10 remains equal is by increasing (decreasing) R or decreasing (increasing) P . Usually R is the same as F and

does not change, so we are left with one option: decrease (increase) P . Do not worry if you feel lost here, we will

show that this makes sense intuitively. For example, there is a bond with a face value $5, the buyer of the bond gets

$1 each year for the next 10 years and $5 at the end of 10 years. If you want to impress your boss, then you need

a higher yield per period rate, so paying $4 to get the package would be much better (higher yield per period rate

than paying $5) than paying $6 to get the exact same package (lower yield per period rate than paying $5).

5. The previous bullet point also makes sense mathematically: under the assumption that R = F , 10 is of the form

P = xanq +Rvn

= x1

(1

1+i

)ni

+ F

(1

1 + i

)n

= x1

(1

1+i

)ni

+ Fi

(1

1+i

)ni

= (x Fi)1

(1

1+i

)ni

+ F= (Fr Fi)

1(

11+i

)ni

+ F= F (r i) anq + F. (11)

(a) If i = r, then P stays the same, P = F .

(b) If i > r, i.e., when the demanded yield per period rate goes up (you want to impress your boss, remember?),

the new P is the sum of F and a negative number, so P goes down, P < F .

(c) If i < r, i.e., when the demanded yield per period rate goes down (there is another person that wants to buy it,

so you are willing to settle for less), the new P is the sum of F and a positive number, so P goes up, P > F .

F (r i) anq is called the premium (if positive) or discount (if negative). It is worth mentioning that, in real life,premium bonds usually come with a higher coupon rate than discount bounds, so people are willing to pay for more

than face value just for the big coupons.

6. Callable bonds are bonds that can be redeemed early by THE BOND ISSUER (no more coupons chaps, here is

your redemption and get out of here). It is intuitively true that a callable premium bond gives the minimum yield

to the investor when called at the earliest possible date, because of an early capital lossyou did pay more than

the face value. Would you be happy if I sell you a $10-par bond for $11 (therefore a premium bond) and call it

-

immediately? No, because you just lost a dollar in one second. Another intuitive way to see it is, remember what

we said earlier, in real life, you buy premium bonds for the big coupons, so the more coupons you get, the better.

Although this is not the case in FMwe often see premium and discount bonds that oer the same couponsthis

is because you are only learning the concepts so it is convenient for the books/guides to use the same numbers

(especially coupon rate) over and over. Just think: if things were like this in real life, then who on earth would buy

a premium coupon when they can buy a discount coupon that oer the exact same amount of returns (dollar-wise)?

Similarly, a callable discount bond gives the minimum yield to the investor when called at the latest possible date,

because of a late capital gainyou did pay less than the face value. Would you be happy if I sell you a $10-par

bond for $9 (therefore a discount bond) and call it immediately? Yes, because you just made a dollar in one second.

7. Callable bonds are priced as low as possible, because investors are all prudentthey are afraid that the bond issuer

might call the bond at the worst time (minimum yield rate to the investor), so they want to pay the smallest P !

A callable premium bond is priced as if it will be redeemed at the earliest possible time (if n gets smaller in 11,

then the premium, a positive number, gets less positive, and so P gets smaller). Similarly, a callable discount bond

is priced as if it will be redeemed at the latest possible time. (if n gets bigger in 11, then the discount, a negative

number, gets more negative, and so P gets smaller). If they are not priced in this way, prudent investors will simply

not buy these bonds.

8. The original formula 10 and the premium-discount formula 11 are two ways to calculate the price of a bond. There

is a third formula, the Makeham's Formula, it is in a way similar to 11instead of the dierence between r and i,

we use the ratio of r and i. Here is the derivation, keep in mind that all of our v and anq are based on i, not r, and

also that R = F is assumed as usual:

P = xanq +Rvn

= x1

(1

1+i

)ni

+K

= Fr1

(1

1+i

)ni

+K

=r

i

(F F

(1

1 + i

)n)+K

=r

i(F K) +K

where K = Fvn = F(

11+i

)n. Also, note that this formula is basically 10 except we write xanq in a fancy way.

So you do not really have to memorize this formula, you can just derive it during the exam, assuming you are

comfortable with calculations. But I personally nd this formula cute and decided to memorize it.

9. Assuming R = F , principal of premium or discount paid in period t is F (r i) vnt+1. But wait a minute, this looksjust like 9, except we use F (r i), which is a small number. But it makes sense, because the premium or discount isa (relatively speaking) small number to begin with! Also, notice that, when r > i, F (r i) is positive, because thepremium is positive, and when r < i, F (r i) is negative, because the discount is negative! It is nice when thingscheck out! Lastly, just like 9 and many other t-in-the-power formulas, when given the value of F (r i) vnt1+1, wecan calculate a dierent F (r i) vnt2+1 by F (r i) vnt2+1 = F (r i) vnt1+1 vt1t2 .

10. Make sure you know how to use calculator to calculate date dierence. Price of a bond sold between two coupons:

P0 (1 + i)t tx,

where t = settlement datelast coupon date# of days in this period and P0 is the price immediately after the last coupon date. If you sell thebond to another person immediately after the last coupon date, it would be a brand new bond to that person, the

-

price would be P0 which is easy to compute. However, when the settlement date is in between two coupon dates,

we have two problems:

(a) The bond price (P0) has increased to P0 (1 + i)t(or P0 (1 + ti) if you are asked to use simple interest), because

some time has passed since the bond was worth exactly P0. This part is called the dirty price.

(b) The dirty price uctuates too much, so for appearance purposes, all quote prices take away tx from the dirty

price to obtain the clean price P0 (1 + i)t tx, the clean price is what we use for FM, it is NOT the actualtrading price.

Make sure you know how to use the BOND worksheet on your calculator! The BOND worksheet gives you the

clean price (not using the simple interest), so when the question asks you to nd the purchase price, make sure you

add the accrued interest back on. Also, when the question asks you to use simple interest specically, you have to

calculate P0 (1 + ti) manually and not rely on the BOND worksheet.

11. I am surprised that these did not came up in the rst few chapters, but when the question gives you the value of

vn, say vn = k, yet the bond has semi-annual coupons, make sure you use k2 when you calculate things, because I

am pretty sure that is what you actually need! Also, when the question asks you for the number of yeas a coupon

is held for, always divide your N from the calculator, most likely half years or quarters, by 2 or 4, respectively.

Tricky bastards! My friend says always write down Question #: annually/semi-annually/quarterly(4)/monthly on

the scrap paper and circle it. So something like this,

Question 21, quarterly (4) , should keep those pesky bastards

from stealing points from you.

12. (2005 Exam FM Sample Questions #30) As of 12/31/03, an insurance company has a known obligation to pay

1, 000, 000 on 12/31/2007. To fund this liability, the company immediately purchases 4-year 5% annual coupon

bonds totaling $822, 703 of par value. The company anticipates reinvestment interest rates to remain constant at

5% through 12/31/07. The maturity value of the bond equals the par value. Under the following reinvestment

interest rate movement scenarios eective 1/1/2004, what best describes the insurance company's prot or (loss) as

of 12/31/2007 after the liability is paid?

Insight from this question:

(a) 4-year 5% annual coupon bonds totaling $822, 703 of par value means the coupon is an annual coupon that pays

822703 0.05 = $41135.15 per year for 4 years, this sentence does not tell you about the redemption value yet.Them fancy words!

(b) When you reinvest the coupon payments at the same rate as your bond, and when the redemption rate is par,

then your money is petty much growing at i, like here, 822703 (1.05)4 = 1, 000, 000 which is desired. This ismathematically true, because xsnq + F = xanq (1 + i)

n+ F = (xanq + Fvn) (1 + i)

n= F (1 + i)

n.

(c) But then you might ask, why do I have to reinvest? The yield per period rate i is already at 5%! Because

the coupons that you get do not magically grow according to the bond's yield per period rate i if you do not

reinvestthe x you get from the rst coupon will still be x at the time of redemption if you just let it sit on

your desk!

i. Andrew reinvests at the bond's yield per period rate i, so his original investment is growing at i, so he ends

up with an even over-all yield per period iA = i by reinvesting at i.

ii. Bill reinvests at a rate higher than the bond's yield per period rate i , he ends up with more money than

Andrew in the end, so he achieves a higher over-all yield per period rate iB > iA = i.

iii. Chris reinvests at a lower rate than the bond's yield per period rate i , he ends up with less money than

Andrew in the end, so he achieves a lower over-all yield per period rate iC < iA = i.

-

5 Yield Rate of an Investment

1. The internal rate of return formula is just a special case of the net present value formula:

NPV = C0 + C1v + C2v2 + Cnvn (12)

When you calculate the net present value, i is given so that the left hand side can be calculated. When you calculate

the internal rate of return, the left hand side of 12 is 0 to begin with, you are required to nd v such that the

equation holds. It is nothing but an nth degree polynomial. We are however, only interested in roots that are close

to 1 because v = 11+i is close to 1. Once we solve for v, we can solve for i. The nthdegree polynomial that you are

going to get will be an easy one, it helps to know the quadratic formula and some other simple techniques. But at

the end of the day, you could always nd the answer by trial and error, not recommended but can be a last resort.

2. Know how to use the CF worksheet. When the money at time t1 is reinvested until time t2, the Ct1 entry becomes

0, but the Ct2entry now increases by whatever the total amount of the total payo of the reinvestment is at time t2.

This is very important, you should NEVER keep the Ct1 entry and just add the earned interest to Ct2 . For example,

3. Eective (means actual interest rate +1) rate of time weighted rate of interest is simply the product of eective rate

of interest from equal-length sub-periods,

1 + i = (1 + i1) (1 + i1) (1 + in) . (13)

Notice that in actual exam questions, it may tell you the balance at the end of January 31st, November 30th,

December 31st only, the sub-periods might seem unequal at rst glance, but you can just assume the monthly

interest rate from February 1st to October 30th to be 0, then calculate (1 + i1) 1 1 (1 + i11) (1 + i12).Basically, unless you have negative interest periods and positive interest periods that multiply out to be exactly 1,

like when 0.80 1.25 = 1, the time weighted rate of interest is rarely 0.

4. Dollar weighted Rate of Interest is a little bit more tricky. First, we give the formula for net cashow. Here we do

not care about interest/time value of money at all, it is just elementary addition and subtraction,

Net cashow = End balance Initial balanceNet contribution.

Remember contributions are only deposits (positive contributions) and withdraws (negative contributions) , when

the fund simply drops or increases on its own, we do not count that towards the contribution.

Then, we give the formula for weighted contributions, notice how this is dierent from net contribution because now

we actually care about when these contributions are made,

Weighted contribution =

Ct (1 t) ,

where Ct is the contribution at time t (for example, when the rst contribution is made at the end of the rst month,

when the total period is 1 year, then t = 112 ). Finally, dollar weighted rate of interest given by

Net cashow

Initial balance+Weighted contributions(14)

Keep in mind that in the numerator you subtract the (net) contributions, in the denominator you add the (weighted)

contributions. Do lots of practice because it is very easy to mess up the signs. Word of advice: it is easier to keep

the contributions in a bracket of its own, that way, you do not have to worry about signs too much.

5. Keep in mind that, 13 gives the eective interest rate (1 + i), but 14 gives the actual interest rate.

-

6. Portfolio method and investment year method are pretty straight forward. Just practice with a table until you are

absolutely comfortable with it.

-

6 Term Structure of Interest Rates

1. A zero coupon bond is a bond that does not give any coupons. The nyear maturity quote of a Treasury STRIPzero-coupon bond is the spot rate sn. So 1 dollar today would be worth, n years from now, (1 + sn)

n.

2. Let us look at one simple example,

Year Spot Rate

1 s1 = 2%

2 s2 = 3%

3 s3 = 3.5%

4 s4 = 4%

5 s5 = 4.5%

The price of a four year $1000 par bond with 3% coupon rate, based on the above table, is 301.02 +30

1.032 +30

1.0353 +10301.044 =

965.20.

3. Eective forward rate from time n to time n+ 1 (in, n+1 is called the n-year forward rate) is

1 + in, n+1 =(1 + sn+1)

n+1

(1 + sn)n (15)

The index and power in the numerator are both n+ 1, the index and power in the denominator are both n, so this

should be an easy to remember formula. Notice that a direct result of 15 is

(1 + sn)n

= (1 + i0, 1) (1 + i1, 2) (1 + in2, n1) (1 + in1, n) (16)

where i0, 1 is dened to be s1. 16 makes perfect sense intuitively if you stare at it long enough. It also helps to

realize that the n-year forward rate today is simply the 1year spot rate in year n!

4. One year forward rate for year two means i1, 2. The for year two part is redundant and meant to trick you into

calculating i2, 3 instead. Remember the n-year forward rate is simply in, n+1.

5. One year eective rate during year n is simply in1, n. This is just a dierent way of saying (n 1)-year forwardrate.

6. (Nov 05 #15) You are given the following term structure of spot interest rates:

Term (in years) Spot Rate

1 s1 = 5%

2 s2 = 5.75%

3 s3 = 6.25%

4 s4 = 6.5%

A three-year annuity-immediate will be issued a year from now with annual payments of 5000. Using the forward

rates, calculate the present value of this annuity a year from now.

Insight from this question:

(a) A three-annuity-immediate issued one year from now means the rst of the three payments do not come in until

2 on the time axis.

(b) The question itself is easy to solve, we can simply calculate the current value of the payments and then multiply

by 1.05:(

50001.05752 +

50001.6253 +

50001.0654

) 1.05(c) However, this question and its solution provided by ACTEX raises an interesting issue: how do we calculate

spot rate and forward rate at a future time? The 1-year spot rate n year from now, s (n)1 is simply the

-

n-year forward rate today, in, n+1 =(1+sn+1)

n+1

(1+sn)n . The 2-year spot rate n year from now, s (n)2, must satisfy

(1 + s (n)2)2

= (1 + in, n+1) (1 + in+1, n+2) =(1+sn+1)

n+1

(1+sn)n

(1+sn+2)n+2

(1+sn+1)n+1 =

(1+sn+2)n+2

(1+sn)n . Similarly, (1 + s (n)3)

3=

(1+sn+3)n+3

(1+sn)n . So in general, we have, the k-year spot rate n year from now is

(1 + s (n)k)k

=(1 + sn+k)

n+k

(1 + sn)n . (17)

17 makes perfect sense if we move the denominator to the left hand side and obtain

(1 + s (n)k)k

(1 + sn)n

= (1 + sn+k)n+k

.

Also notice that, when n = 0, that is, when we talk about today, 17 gives (1 + sk)k

= (1 + sk)kwhich is

trivially true!

-

7 Term Structure of Interest Rates

1. Macaulay duration, D (i) = D, is a function of i.2 This is an important concept, you have to remember that you

are dealing with a very complicated function here, not just a number.

D (i) =vC1 + 2v

2C2 + . . .+ nvnCn

vC1 + v2C2 + . . .+ vnCn

=

(1

1+i

)C1 + 2

(1

1+i

)2C2 + . . .+ n

(1

1+i

)nCn(

11+i

)C1 +

(1

1+i

)2C2 + . . .+

(1

1+i

)nCn

, (18)

where Ck's are investment cash ows at time k. It is worth mentioning that, when Ck's are non-negative, 1 D nas shown below, let

(1

1+i

)kCk = ak. Since ak's are positive, we have

1 =a1 + a2 + . . .+ ana1 + a2 + . . .+ an

a1 + 2a2 + . . .+ nana1 + a2 + . . .+ an

= D na1 + na2 + . . .+ nana1 + a2 + . . .+ an

= n.

Usually we write vC1 + v2C2 + . . . + v

nCn = P (i) = P because it is the net present value (the price) of the

investments.

2. Modied Duration,

M (i) = M = vD = P

P. (19)

This is how I remember M = vD, like in sports they have MVPmost valuable player, MVDmost valuable

duration.

3. If you clearly understand 18, then you do NOT need to memorize any of the level payment/bond/zero-coupon bond

duration formulas. They are all easily followed if you write out 18. I will do it for you here, but make sure you do

it on your own.

(a) Level payments with payments x, the duration is

D =vC1 + 2v

2C2 + . . .+ nvnCn

vC1 + v2C2 + . . .+ vnCn=vx+ 2v2x+ . . .+ nvnx

vx+ v2x+ . . .+ vnx=v + 2v2 + . . .+ nvn

v + v2 + . . .+ vn=

(Ia)nqanq

.

It helps that you remember the denominator of D is the price/net present value of the cashow, so the above

formula makes perfect sense.

(b) Bonds with payments x and redemption payment R, the duration is

D =vx+ 2v2x+ . . .+ nvn (R+ x)

vx+ v2x+ . . .+ vn (R+ x)=x (Ia)nq + nv

nR

xanq + vnR.

Again, it helps that you remember the denominator of D is the price/net present value of the cashow, so the

denominator is just the price of the bond! It is very important that during the exam, you must not forget to

multiply R with n.

(c) Bonds with payments x and redemption payment xi , notice that the most common bond satisfying this condition

2

We write D (i) = D to mean that we will use D for Macaulay duration sometimes for convenience, even though it is a function of i really.

-

is just an r = i par bond, the duration is

D =x (Ia)nq + nv

n xi

xanq + vn xi

=(Ia)nq +

nvn

i

anq + vn

i

=

(anq +

(anqnvn

i

))+ nv

n

i

1vni +

vn

i

=anq +

(anqi

)1i

= anq

(1 +

1

i

)i

= anq (1 + i) = anq.

(d) Zero-coupon bonds

D =vC1 + 2v

2C2 + . . .+ nvnCn

vC1 + v2C2 + . . .+ vnCn=nvnR

vnC= n.

Notice that is is also the maximum of the Macaulay duration function, it is achieved precisely when there is

only 1 nal payment. Can you spot when the minimum is achieved?3

4. When you write FM, many duration questions can be solved by simply calculating M = P P once you gure outwhat P is (do NOT plug in i yet), M is usually a nice function because P and P often have common factors andsimplify beautifully. Then once you have M , plug in the given i to get a number, then do D = M (1 + i). The key

point here is you do NOT plug in i in the early steps.

5. It helps to know the Taylor series, it is such a widely-used formula, you might as well memorize it.

f (x) = f (a) +f (a)

1!(x a) + f

(a)2!

(x a)2 + f(3) (a)

3!(x a)3 + . (20)

So we let x = x+ x and let a = x in 20, we obtain

f (x+ x) f (x) = f (x)1!

x+f (x)

2!(x)

2+f (3) (x)

3!(x)

3+ . (21)

And luckily, for FM, we only need the rst two terms of the right hand side of 21

f (x+ x) f (x) = f (x) x+ f (x) (x)2

2. (22)

22 makes sense intuitively, the change of the value of f after shifting x by a tiny x is directly aected by two

things:

(a) The change in x ( means change), but we need to multiply the change in x, x, by the rst derivative, which

is a measure of how a function changes as its input changes.

(b) Half of the square of the change in x, that is, (x)2

2 , but we also need to multiply that by something, seeing it

has a second power, we need to multiply it by the second derivative.

Sometimes, we only need one term.

f (x+ x) f (x) = f (x) x. (23)

Now to apply the above knowledge. Recall that M = P P , so P = MP . Using 19 and 23, we have,

P (i+ i) P (i) = P = MPi = vDPi. (24)3

The minimum is also achieved precisely when there is only 1 nal payment that arrives at time 1, that is, when n = 1.

-

Next, the convexity of a P is dened to be4

=P

P. (25)

So P = P . Using 19 and 22, we have,

P (i+ i) P (i) = P = MPi+ P (i)2

2= vDPi+ P (i)

2

2. (26)

I understand that 24 and 26 are both hard to memorize, but if you go through the derivation above a few times,

and memorize the small formulas (they are the building blocks of the big formulas!) like 19, 22 and 25, it becomes

a lot easier.

6. The duration of a portfolio, in which all investments have the same interest rate shift, is the weighted average of the

durations of the investments. You really do not have the need to memorize this formula, but here it is anyways,

D =k

wkDk

and

M =k

wkMk,

where the wk's are the weights based on the investment amount, so bigger investment = bigger weight, smaller

investment = smaller weight.

wk =PkP

7. Immunization is where you have to keep reminding yourself that P = P (i). Take any random function of x,

f = f (x), as long as it is not too complicated, you should be able to dierentiate it with respect to x to obtain

f = f (x), and then dierentiate it again to obtain f = f (x). Immunization is pretty much just this. Let Astand for asset and L stand for liability, i0 some interest, in order to achieve immunity near i0, we need three criteria,

PA (i0) = PL (i0) ,

P A (i0) = PL (i0) ,

and

P A (i0) > PL (i0) .

It is important to realize that all P , P and P are functions of i, so with the bracket (i0) attached to them, it meansto evaluate these functions at i0. Just like if we have f (x) = f = x

2, then f (x) = f = 2x and f (x) = f = 2, wecan evaluate these functions of x at some point, say x0 = 3, f (x0) = f (3) = 3

2 = 9, f (x0) = f (3) = 2 3 = 6and f (x0) = f (3) = 2. Again, these P , P and P are NOT functions of v, we simply use v because it isconvenientthese functions are functions of i. So remember, always dierentiate rst, then evaluate, because if you

evaluate rst, then you get a xed number and the derivative is automatically 0!

8. We can dierentiate with respect to i but keep the result in v. In fact, if f = vk =(

11+i

)k, then

f =(vk)

=d

di

[(1

1 + i

)k]=

d

di

[(1 + i)

k]

= k (1 + i)k1 = k(

1

1 + i

)k+1= kvk+1 (27)

and

f =(vk)

=d

di

(kvk+1) = k [ ddi

(vk+1

)]= k

( (k + 1) v(k+1)+1

)= k (k + 1) vk+2. (28)

4

Pronounced Gamma, it is the standard letter for convexity.

-

notice how these useful results are completely dierent from f = kvk1 and f = k (k 1) vk2 which are completelywrong and probably what you would have expected. This can be explained by realizing that v is a function of i, soddi (f) =

ddv

dvdi (f) =

ddv (f)

dvdi =

ddv (f)

(v2) which utilizes the chain rule.9. If we are given

PA =

Atvt

and

PL =

Ltvt,

then to achieve immunity, we need

(a) Present value matching:

PA (i0) = PL (i0)

Given

Atvt (i0) =

Ltv

t (i0)

Denition of v

At

(1

1 + i

)t(i0) =

Lt

(1

1 + i

)t(i0)

We evaluate these functions of i at i0 and "match" them

At

(1

i0 + 1

)t=

Lt

(1

i0 + 1

)t.

We dene a new vi0 for easier notation

Atvti0 =

Ltv

ti0 (29)

You do not need to memorize 29 as it is intuitively true and easy to set up. Again, just to emphasize, all

of these make sense only because we are given an interest rate i0. We cannot match two functions without

an input. We can only match two evaluated functions. We will look another example. We cannot compare

f (x) = x and g (x) = x2 in general. We can only compare them if we know what input we are using. When

x = x0 = 0.1, we have 0.1 = f (x0) = f (0.1) > g (0.1) = g (x0) = 0.01. When x = x0 = 1, we have

1 = f (x0) = f (1) = g (1) = g (x0) = 1. When x = x0 = 2, we have 2 = f (x0) = f (2) < g (2) = g (x0) = 4.

-

(b) Duration matching:

MA (i0) = ML (i0)

Denition of M

PA

PA(i0) = P

L

PL(i0)

To evaluate

fg (x0) is (usually, so here) the same as evaluating

f(x0)

g(x0)

PA (i0)

PA (i0)= P

L (i0)

PL (i0)

Because we are already matching present value, so PA(i0)=PL(i0)

P A (i0) = PL (i0)

See 27

At(tvt+1) (i0) = AL (tvt+1) (i0)

Multiply both sides by 1v , we can do this because t starts at 1

tAtvt (i0) =

tALv

t (i0)

Denition of v

tAt

(1

1 + i

)t(i0) =

tAL

(1

1 + i

)t(i0)

We nally get to evaluate and "match"tAt

(1

1 + i0

)t=

tAL

(1

1 + i0

)tEasier notation

tAtvti0 =

tALv

ti0 (30)

30 is similar to 29 except with an extra t, you need to memorize it. Also try to understand the reasoning behind

each .

-

(c) Greater convexity for assets:

A (i0) > L (i0)

Denition of

P APA

(i0) >P LPL

(i0)

Same as above

P A (i0) > PL (i0)

See 28

At(t (t+ 1) vt+2

)(i0) >

AL(t (t+ 1) vt+2

)(i0)

Multiply both sides by

1v2, we can do this because t starts at 1

At(t (t+ 1) vt

)(i0) >

AL(t (t+ 1) vt

)(i0)

We are simply breaking the bracket on both sides

t2Atvt (i0) +

Atv

t (i0) >

t2Ltvt (i0) +

Ltv

t (i0)

Denition of P

t2Atvt (i0) + PA (i0) >

t2Ltv

t (i0) + PL (i0)

Again, because PA(i0)=PL(i0)t2Atv

t (i0) >

t2Ltvt (i0)

Denition of v

t2At

(1

1 + i

)t(i0) >

t2Lt

(1

1 + i

)t(i0)

We nally get to evaluate and "match"t2At

(1

1 + i0

)t>

t2Lt

(1

1 + i0

)tEasier notation

t2Atvti0 >

t2Ltv

ti0 (31)

31 is also similar to 30 except with yet another t, you need to memorize it. But again, try to understand the

reasoning behind each .

10. The price formula for a equal-dividend stock is pretty trivial, it is just the rst dividend, x, multiplied by 5,

x

i g (32)

Notice that,

(a) When g = 0, it means that the dividend is not increasing and stays x forever.

(b) When g > i, 32 is meaningless and useless because the stock price diverges.

11. For the simple liability matching questions, always calculate the longest investment rst because the earlier coupons

of it can go towards the earlier liabilities. Never try to calculate the bond price on paper, use your calculator. The

less calculation you do with pen and paper, the less chance of making stupid arithmetic mistakes.

-

12. Because 29 and 30 are both equalities, sometimes you are asked to solve an immunity question using those two. Two

equations means they can only give you two unknowns. What you need to solve is probably something like thisa = bx+ cyd = ex+ fywhere x and y are unknowns and represent money put into two investments. If you know that the determinant of a

2 2 matrix(a b

c d

)is ad cb. It is then easy to solve a system of equation like this using Cramer's rule:

x =

det

a cd f

det

b ce f

= afdcbfec

y =

det

b ae d

det

b ce f

= bdeabfec

The denominator is always the determinant of the coecient matrix

(b c

e f

), and the numerator is the determinant

of the coecient matrix where the corresponding unknown's coecients replaced by the column vector

(a

d

). Ignore

this if you did not get A in linear algebra.

13. This really belongs somewhere in the beginning, but again, make sure you calculate the eective/nominal rate as

requested, do not calculate one when the question is asking for the other.

14. The full immunization technique is designed to work for any change in the interest rate. I previously thought for

only small changes. I was wrong.

-

Part II

Financial Economics (20 35%)8 General Derivatives

1. A stock index is an average of the prices of stock in a specic group.

2. The spot price is the current price of an asset at any time.

3. Payo is the value of the nancial result at expiration. Prot or net payo is payo less the future value (at

expiration) of any expenses incurred in setting up the nancial structure involved. A zero coupon bond's payo is

the redemption value, its prot or net payo is 0.

4. A derivative is an agreement between two people that has a value determined by the price of the underlying asset

(stock, corn, wine, etc.).

5. Derivatives are used to

(a) Reduce risk (at a cost of reduced prot), called hedging.

(b) Increase risk (in an attempt to prot), called speculation.

(c) Capitalize on loopholes in regulatory systems in order to circumvent unfavorable regulation, called regulatory

arbitrage.

6. Bid-ask spread is the amount by which the ask price exceeds the bid price of the same asset at the same time.

Bid-ask spread is easy if you remember that the investors (who enter into derivative contracts for the three reasons

listed in (5)) are always screwed by the market makersintermediaries or traders who will buy/sell derivatives from

customers who wish to sell/buy: the investors have to buy high at ask price and sell low at bid price.

7. Over-the-counter market is where buyers and sellers transact with banks and dealers rather than on an exchange.

So it is dicult to obtain statistics for its volume.

8. The typical, easy to understand buy-today&sell-tomorrow is called lendingyou pay cash to receive the underlying

asset and late sell it to receive (hopefully more) cash. You are said to have a long position.

9. Short-selling is the exact opposite of lendingyou borrow the asset, sell it for cash, then later buy back the asset

and return it. You will most likely have to pay lease rate, which does not get returned to you, to short sell. You are

said to have a short position.

10. Short-sell can happen for at least three reasons that are not mutually exclusive,

(a) Speculation, you aim to sell high and then buy low to make a prot.

(b) Financing, it is a common way to borrow money.

(c) Hedging, you can oset the risk of owning the stock or a derivative on the stock. Usually done by market-makers.

11. Short-sell has two major issues,

(a) Credit risk, as the short seller, you have an obligation to return the asset. The lender may hold onto your proceed

you received from selling the asset, and also require you to hand over an extra amount, called a haircut. When

you return the asset, say after one period,

Collateral (1 + Repo rate)

-

(where Collateral is basically Proceed+Haircut. Repo rate is also called Short rebate) is returned to you.

Obviously, repo rate/short rebate is lower than the market rate of interest, or even zero when the asset borrowed

is scarce and hard to replace.

(b) Scarcity risk, again, it might be hard to nd someone willing to lend you the asset.

12. Mark to Market is a measure of the fair value of assets or liabilities that can change over time.

13. The margin is a performance bond that can earn interest, NOT a premium. Both buyers and sellers are required

to post a margin with the broker to protect the counterparty against your failure to meet your obligations. If a loss

occurs, you can choose to pay it directly; or allow it to be taken out of the margin balance.

14. Participants are required to maintain the margin at a minimum level, called the maintenance margin. This is often

set at 70% to 80% of the initial margin level.

15. When the margin balance drops below the maintenance margin, the broker would make a margin call, requesting

additional margin. Failing to post additional margin would cause the broker to close the position, and return to the

investor the remaining margin.

-

9 Options

1. Stockholders are typically paid a share of the company's prots called dividends.

2. A forward contract is a contract to buy or sell a specied asset at a designated future time. The forward contract

should specify

(a) Underlying asset. The type and quantity of the asset to deliver.

(b) Expiration date. Time, place and date of delivery.

(c) The sale price.

3. The buyer in the forward contact assumes a long position and the seller assumes a short position. Remember, the

long position holder always benets if the price of the asset goes up, just like in (8), in fact they have the same

prot function. Similarly, the short position holder always benets if the price of the asset goes down, just like in

(9), they have the same prot function.

4. At future exchanges, forward contract can be written for cash settlement in which a net payment is made for the

dierence between the spot price at expiration and the forward price.

5. Let t = 0 and t = T denote the beginning and the expiration of the forward contract. Let S0 and ST denote the

asset prices at t = 0 and t = T . Let F0, T denote the forward price at t = 0 for a forward contract expiring at t = T .

Let r denote the continuously compounded interest rate for the forward buyer and seller. We then have

F0, T = S0erT

and

Prot of long forward = ST S0erT = Prot of short forward.

6. Options:

(a) European: can be exercised only on the expiration date.

(b) American: can be exercised any time.

(c) Bermudan: can be exercised only during specied periods.

7. The price of an option is called the premium, it is, of course, what the option buyer gives to the option seller.

8. Strike price or exercise price is the agreed settlement price.

9. The option buyer is also called the option purchaser. The option seller is also called the option writer. I just use

buy and sell so I do not confuse myself.

Call, can buy if protable

With respect to option Buyer Seller

With respect to asset Buyer Seller

Prot/Position Long Short

(33)

This is how I remember this chart: on the left, we have BBB (long means big), on the right, we have SSS.

Put, can sell if protable

With respect to option Seller Buyer

With respect to asset Buyer Seller

Prot/Position Long Short

(34)

-

This is how I remember this chart: rst row (with respect to option) is the opposite of the previous chart, the rest

stay the same. When you take the exam, you will write down (33) and (34) on your scrap paper right after the exam

begins.

5

10. Regarding the payo and prot graph of options. Since the horizontal axis is the price of the asset at expiration, all

you need to remember is,

(a) When the price of the asset at expiration is low, nothing will happen with a call, so the left part of the payo

graph should be horizontal for both call buyers and call sellers.

(b) When the price of the asset at expiration is high, nothing will happen with a put, so the right part of the payo

graph should be horizontal for both put buyers and put sellers.

(c) It remains to see that, the right part of the call payo graph and the left part of the put payo graph go up

or down for long or short positions respectively because as we mentioned multiple times already: long position

makes money when the price goes up, and short position makes money when the price goes down.

Once you have the payo graph, the prot graph is obtained by a simple vertical shift of the pemium amount, it

shifts up for the option seller (who gets the premium) and down for the option buyer (who pays the premium).

11. An option is in/at/out of the money if the payo would be positive/0/negative if the option were exercised imme-

diately.

12. To see how homeowner's insurance can be viewed as an option.

(a) First realize that it is a put option as no one is trying to buy the underlying asset, the house.

(b) Next realize that, if the value of the house goes down (for example, a re), then the home owner makes money

by selling it, so he is in the short position, so he is the put buyer.

(c) Lastly, the strike price is of course the house price subtract the deductible. It is subtraction, not addition

because in the case that the house suers a small damage, the house owner does not get to claim it, which

means he does not exercise the put, which means the strike price should be lower than the house price.

13. Covered writing, option overwriting, or selling a covered call is the opposite of a cap. Covered put is the opposite

of a oor. We rst use a pair of charts to summarize these four and memorize them with brute force. It is not too

hard, I will explain.

Prot Equivalent

Cap Short Index & Long Call Short Put

Covered Call Long Index & Short Call Long Put

and

Prot Equivalent

Covered Put Short Index & Long Put Short Call

Floor Long Index & Short Put Long Call

Notice that in these charts, the terms long/short with respect to options refer back to (33) and (34). So for example,

long call would be the equivalent of buy call, similarly, long put would the equivalent of sell put.

(a) First Notice how the position with respect to the index (we use stock index instead of the usual word asset here,

you will see why) is always the opposite of the position with respect to the option? So even without knowing

anything, you can recreate the middle column of the two charts:

Prot Equivalent

Short Index & Long Call

Long Index & Short Call

5

See 11 for a complete short list of important formulas that you should write down at the beginning of the exam.

-

and

Prot Equivalent

Short Index & Long Put

Long Index & Short Put

(b) Next, the equivalent option in the last column is always the opposite of the option in the middle, with the

position opposite of the position with respect to the option in the middle (this sentence is long, but it is really

simple and staight forward). So you can ll in some more blanks without knowing a lot:

Prot Equivalent

Short Index & Long Call Short Put

Long Index & Short Call Long Put

and

Prot Equivalent

Short Index & Long Put Short Call

Long Index & Short Put Long Call

(c) Next, cap, is a hat, so it is made by silc (silk). Therefore cap goes into the row with Short Index & Long Call.

The other one is then covered call.

Prot Equivalent

Cap Short Index & Long Call Short Put

Covered Call Long Index & Short Call Long Put

(35)

(d) Lastly, oor, has the exact opposite (literal meaning, not mathematical) prot equivalent of that of capequivalent

to short put, so it goes into the row with long call as prot equivlant. The other one is then covered put.

Prot Equivalent

Covered Put Short Asset & Long Put Short Call

Floor Long Asset & Short Put Long Call

(36)

This may seem long because I wrote out the entire thinking process one step at a time. When you take the exam,

you will write down (35) and (36) on your scrap paper right after the exam begins.

6

14. Now I will try my best to explain the two charts.

(a) A covered call is the opposite of a naked call, which is when you sell a call without owning the actual asset,

you can easily see why this would be dangerousif the price of the asset gets too high, you would be broke

because you cannot provide the asset when the call buyer excersise the option. So to avoid naked call, when

you sell a call, you also buy the asset, then you have a covered call.

(b) A cap is when you short an asset, but you are afraid that when the price of the asset gets too high, you would

be broke because you cannot return the asset when it is time to do so. So to avoid paying too much for the

asset in the future, you buy a call to cover your behind.

(c) Covered put is when you sell a put, but you are afraid that when the price of the asset gets too low, you

will end up spending a lot of money on something that is not worth a lot. So to make the (potential) pain

more bearable, you short the asset. This way, when the asset gets too low, at least you made money from the

short-sale of it.

(d) Floor is just like insurance. You buy an asset, but you are afraid that it will depreciate, so you buy a put to

cover your behind.

6

See 11 for a complete short list of important formulas that you should write down at the beginning of the exam.

-

15. Synthetic forward mimics a long (again, long means the party that makes money when the price of the asset goes

up) forward position on an asset by buying a call and selling a put, with each option having the same strike price

and time to expiration. Net income from the premiums of a synthetic forward is Put (K,T )Call (K,T ). Net costof synthetic forward is the opposite, Call (K,T ) Put (K,T ).

16. Put-call parity is

Put (K,T ) Call (K,T ) = PV (K F0, T ) (37)

(37) makes pefect sense because if you create a synthetic forward with strike price K, then the present value of the

dierence between K and the forward value of the asset should be the same as the dierence between your income

from selling the put and expense from buying the call. When K gets smaller than F0, T , the right hand side becomes

negative. But at the same time, the more you have to pay for the call because it would seem like a really good deal

to you (bad to the call seller), so the left hand side becomes negative too. When K gets bigger than F0, T , the right

hand side becomes positive. But at the same time, the more you get from selling the put because it would seem like

a really good deal to the put buyer (bad to you), so the left hand side becomes positive too.

-

10 Hedging and Investment Strategies

1. Diversiable risk is unrelated to other risks, such as a lightning strike. Undiversiable risk is the opposite, such as

a stock market cash. There exist risk-sharing mechanisms that benet everyone.

2. Catastrophe bonds are bonds that the issuer need not repay if there is a specied event, such as a large earth quake.

Here is an example of tiered risk-sharing.

Policyholder Insurer Reinsurer Catastrophe bond

Note that, an insurer that purchases reinsurance is also called the "ceding company" or "cedant".

3. Arbitrage is the simultaneous purchase and sale of an asset in order to prot from a dierence in the price. It is a

trade that prots by exploiting price dierences of identical or similar nancial instruments, on dierent markets or

in dierent forms. Arbitrage exists as a result of market ineciencies; it provides a mechanism to ensure prices do

not deviate substantially from fair value for long periods of time.

4. An option spread is a position consisting of only calls or only puts.

(a) Bull spread is what you do when you expect the market value of an asset to increase. Remember it by realizing

that you simply buy low and sell high (which in a way agrees with the word increase, just remember that buy

comes before sell). You can do it with both call and put.

(b) Bear spread is what you do when you expect the market value of an asset to decrease. Remember it by realizing

that you simply buy high and sell low (which in a way agrees with the word decrease). You can do it with

both call and put.

5. A box spread is simply two synthetic forwards. It builds a zero coupon bond. Done in an attempt to lower taxes.

6. Buy collar is buy low put and sell high call. Sell collar is buy high call and sell low put.

(a) Remember this by noting that the sum of the two options is always the opposite of the position with respect

to the collar. It is always the opposite of what you would expect.

i. buy low + sell high, you expect the result to be sell because there is more sell, but it is actually buy low + sell high = buy collar.ii. buy high + sell low, you expect the result to be buy because there is more buy, but it is actually buy high + sell low = sell collar.(b) The high one is always the call because call sounds similar to collar.

(c) The collar can be used to hedge the price of a purchased asset.

-

Part III

Appendix

11 List of Formulas to Write Down at the Beginning of FM

(t) =a (t)a (t)

astart amount

eend time

start time

(u)du = aend amount

Panq +Q(anq nvn

i

)anq =

1 vni

Call, can buy if protable

With respect to option Buyer Seller

With respect to asset Buyer Seller

Prot/Position Long Short

Put, can sell if protable

With respect to option Seller Buyer

With respect to asset Buyer Seller

Prot/Position Long Short

Prot Equivalent

Cap Short Index & Long Call Short Put

Covered Call Long Index & Short Call Long Put

Prot Equivalent

Covered Put Short Asset & Long Put Short Call

Floor Long Asset & Short Put Long Call

I Interest Theory (65-80%)Interest Rates and Time Value of MoneyAnnuitiesLoan RepaymentBondsYield Rate of an InvestmentTerm Structure of Interest RatesTerm Structure of Interest Rates

II Financial Economics (20-35%)General DerivativesOptionsHedging and Investment Strategies

III AppendixList of Formulas to Write Down at the Beginning of FM