A Word from Our President T - Communicantes Report Communicantes 201… · Ukraine is quite a...

Transcript of A Word from Our President T - Communicantes Report Communicantes 201… · Ukraine is quite a...

-

1F o u n d a t i o n C o m m u n i C a n t e s ◆ a n n u a l r e p o r t 2 0 1 3

A Word from Our President

Annual Report 2013 of the Foundation Communicantes

ΚοινωνοῦντεϚ/CommunicantesταῖϚ χρείαιϚ τῶν ἁγίῶν κοινωνοῦντεϚ (Rom. 12,13)

ContentsA Word from Our President 1Crisis in Ukraine (and in Europe) 2Communicantes’ Mission 5+7

Projects 2013 6 About Communicantes 8

This year Communicantes is celebrating its 40th anniversary. Of course, we will do this in our own down to earth manner. Continuing a mission which was set out by our founder Jan Bakker s.s.s., Com-municantes pursues an ideal of connect-ing Church and believers in Eastern and Western Europe. Since January, we do this from our new office in Tilburg.

Our motto embodies this mission. It is present in the John Donne meditation ‘No man is an island’, in the writings of the Roman Catholic mystic Thomas Mer-ton and in the 2003 apostolic adhortation Ecclesia in Europa of the recently canon-ised Pope John Paul ii. They emphasise in their own right oneness, solidarity or unity of the European continent.

Europe is not very much in vogue and many find it difficult to decide wheth-er there is too much or too little of Eu-rope today. Looking at the standoff be-tween Ukraine and Russia, one thing is certain. There is not enough Europe to as-sert Ukraine’s drive for dignity and free-dom or to tackle Russian assertiveness.

There are many critics of Europe. They make up a curious ensemble of ultra-na-tionalist right-wingers, on the one hand, and of anti-American, anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist (former) leftists, who play down Western values and achieve-ments, on the other. Sharing a profound disdain for the Western world as it is, they claim it became far too dominant, liberal, relativist, ideologically intolerant or far too religious still.

By the way, a lot of them have a soft spot for President Vladimir Putin’s Rus-sia. In Putin they see a tough leader, who advocates a seemingly straightforward national-moral agenda. Others praise his defiance of the us and its allies.

Unfortunately, many Christians too have grown weary of Europe.

It will be challenging for Communi-cantes to promote a positive role for Christians in Europe and for various rea-sons. With Ecclesia in Europa, however, we have a mighty weapon in our armoury.

Professor Nico Schreurs,President of Communicantes.

-

2 F o u n d a t i o n C o m m u n i C a n t e s ◆ a n n u a l r e p o r t 2 0 1 3

To ask ourselves now what kind of les-sons we may draw from the crisis in Ukraine is quite a hazardous task. After all, seven months of real and artificial chaos have passed and, still, the country remains in limbo over whether the future will be freer and more democratic.

Let us go back for a moment to that eventful month of November 2013. Pro-tests erupted all over the country against President Viktor Yanukovych’s decision to pull out of an association deal with the European Union. Soon, they developed into a popular movement. Its aim was to remove the corrupted president and his cronies from power.

When peaceful protesters occupied Independence square in the centre of Kyiv, the EuroMaidan was born. Eventually, police violence was answered by the pro-testers, culminating in 88 deaths within 48 hours at the end of February 2014.

Clinging on to his winner-takes-all politics and formal democratic pro-cedures, as did his Russian supporters, President Yanukovych would not budge. Before fleeing to Russia on 22 February, he did not make one single concession.

Although the EuroMaidan protest in Kyiv was preceded by smaller Maid-ans, for example following the cover-up of a brutal rape in July 2013, the large scale and nationwide anti-government dem-onstrations came as a surprise. In recent years, the general mood in Ukraine had been rather passive and low. It seemed to exclude real political change.

Feelings of stagnation, hopeless-ness and impotence can be traced back to a variety of causes: the economic crisis, increasing poverty, ever higher levels of corruption and repression, and the quali-ty of public services steadily decreasing.

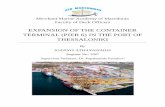

Crisis in Ukraine (and Europe)What Does the EuroMaidan Mean to Us?

Independence square in Kyiv

on 20 February 2014: the worst

fights for the possession of the Euro-

Maidan are over.

Within 48 hours 88 protesters

and police officers

died.

-

3F o u n d a t i o n C o m m u n i C a n t e s ◆ a n n u a l r e p o r t 2 0 1 3

The disappointment surrounding the 2004/2005 Orange Revolution was yet another reason for apathy. After all, the Orange Revolution carried with it great expectations, a promise of a radical break with the past, but ended in great disillu-sion. In fact, the rivalry between protest leaders, President Viktor Yushchenko and Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, un-dermined the new government and pre-pared the advent of Viktor Yanukovych.

In spite of a poorly developed civil so-ciety and the fact that more and more people felt intimidated into submission, it was clear to see that the November pro-tests touched a nerve among a large part of the population. Ukrainians took to the streets to claim a better future for them-selves and their country.

Unlike ten years earlier, this pro-test was more of an all-Ukrainian phe-nomenon. The Eastern-Western Ukraine antagonism, which until then explained much of the country’s balancing act be-tween Europe and Russia, played a less important role then.

All over Ukraine people were pre-pared to risk their future, even their life. Participation in any protest could have resulted in something relatively harm-less like receiving a fine, having your car confiscated, losing your job or being ex-pelled from university. More serious con-sequences were imprisonment, battering, torture or even death.

Churches have been vocal in the pro-tests against the Yanukovych govern-ment too. Like in 2004/2005 the Ukrain-ian Greek Catholic Church, its believers and the Ukrainian Catholic University gave moral support, but many other con-fessions and religions joined in. Roman and Greek Catholic Church leaders ex-pressed their discontent with the current government.

Patriarch Filaret of Kyiv of the un-canonical but important Ukrainian Or-thodox Church expressed his support. At a press conference in March he remind-ed his audience that when his ‘Church stopped praying for the government... the government fled.’ The Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate claimed the moral high ground when it declared itself neutral. While the Church leadership in Moscow more or less adapted itself to state policies, believers, priests and individual

Greek Catholic Father Mychailo Dymyd gives a blessing to a passer-bye at the Independence square in the centre of Kyiv. Dymyd became one of chaplains of the EuroMaidan. In spite of intimida-tion and threats, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church has been a big inspira-tion and moral support to the anti-gov-ernment protests, which took off at the end of November 2013.

-

4 F o u n d a t i o n C o m m u n i C a n t e s ◆ a n n u a l r e p o r t 2 0 1 3

bishops on the ground detached them-selves from the official line and became agents of change.

The Lutheran pastor of the Kyiv Saint Catherine’s church, Ralf Haska, came to fame, when he put himself as a human shield between protesters and riot police. There were many other acts of religiously inspired bravery.

On a larger scale the presence of Roman and Greek Catholics, Orthodox, Muslims and Jews was a testimony to a spirit of mutual respect and tolerance. Meanwhile, the Kremlin tried to frame the protests as a fascist and anti-Semite coup, to some degree successfully. Rus-sian propaganda keenly presented the

right-wing Freedom Party (Svoboda) as the embodiment of the protest. This claim, however, was rebuked by leading figures from the Jewish community, like Josef Zisels, who in turn accused Russia of or-chestrating anti-Semite transgressions.

Unfortunately, the participation of Or-thodox priests in the EuroMaidan protests was taken as an opportunity for the quite famous Roman Catholic Word on Fire website to argue against married priests. Apparently unaware of the many Oriental Catholic Churches, the website published a picture of a priest with the caption: ‘Why I don’t want priests to mar-ry.’

Since married priests are common in the Greek Catholic Church this could not and did not happen in Ukraine. Ro-man and Greek Catholics stood firmly side by side.

The Churches have done well during the Ukraine crisis. Taking care of the spiritual needs of the activists they were bold and courageous enough to point the finger at real issues, notably the corrupt-ed government of President Yanukovych and its lack of respect for the people who brought it to power.

The pro-European stance of the Churches and of many Ukrainians, be they believers or not, is an expression of a profound desire for a dignified life, rule of law and an end to corruption. Yet, the atti-tude towards Europe remains ambivalent. Especially, the ‘moral dictates’ and politi-cal liberal ideology of Europe do not go down well. Partly, this attitude is based on misunderstandings and prejudice, partly on real differences of opinion.

Among Ukrainians, there exists a genuine will to change. They need our sympathy and, above all, our support in building a better future, even if their ide-als do not exactly match our own.

Makeshift hospitals and dormitories were created in church buildings in the centre of Kyiv, like the famous Michae-livsky monastery. Doctors and nurses volunteered and carried out their work in difficult circumstances.

-

5F o u n d a t i o n C o m m u n i C a n t e s ◆ a n n u a l r e p o r t 2 0 1 3

With the clear intent to reshape our original mission of building bridges between the Roman Catholic Church in the Netherlands and in Eastern Europe, Communicantes has embarked on a road towards the exchange and dialogue pro-gramme Communicantes 2.0.

The overall goal is to focus on coun-tries of Eastern and of Western Europe (the Netherlands) and to create a live-ly conversation between believers and Church organisations. At the centre of this discussion is the following question. How and to what extent can our Catholic, Christian or religious identity become a moving force, when we as believers want to actively contribute to the public welfare (bonum commune) of Europe?

An important incentive for doing so is the appeal of the recently beatified Pope John Paul ii in his apostolic adhor-

tation Ecclesia in Europa (2003). There, Pope John Paul very much insisted on the special role of Europe in world history and of Christianity as its main engine.

And very much like our saintly Pope and true to our mission, we want to in-tegrate an ecumenical dimension in our exchange and dialogue programme. Per-haps it will even become possible, here and there, to look at the interreligious dialogue as well.

Drawing on Jewish, Greek and Roman cultural heritage, Christianity came of age in a specific region: Europe. This is why the late John Paul ii so strongly reminded Christians, Churches and the Roman Catholic Church in particular to remain aware of their vocation in Europe. Catholics, the Pope emphasised, must ac-tively contribute to the wellbeing of all.

Communicantes’ Mission “2.0”On Being a Christian in Europe in Our Century

»»» continue on page 7 »»»

On the evening of 24 November 2013, these newly-weds came to the Freedom pros-pect in Lviv to profess their love and their desire to see Ukraine make a step closer to Europe.

-

6 F o u n d a t i o n C o m m u n i C a n t e s ◆ a n n u a l r e p o r t 2 0 1 3

Projects 2013•

Europe – Scholarships for participants of various European networks: * the European Alliance of Catholic Women’s Organisations (Andante) * conference of the European Society of Women in Theological Research (eswtr) * the Argau Summer University of the Commission of the Bishops’ Conferences of the European Community (comece). – Small scholarships for exchange and study trips.

Belarus

– Ecumenical volunteers’ programme of the Greek Catholic Church in Vitebsk. – Roman Catholic Caritas Grodno: prison rehabilitation programme.

Hungary – Lithuania – Romania – Ukraine

– Councils of Major Superiors of Women Religious: * informal training * secretarial costs * strategy planning * scholarships for sisters. Latvia

– Youth pastoral care programme of the Sisters of the Eucharistic Jesus (sje).

Lithuania

– Caritas Lithuania’s programme for victims of women’s trafficking. – Study programme for permanent deacons. – Training and retreat centre Guronys of the sisters Sje.

Moldova

– Psychological training course for lay volunteers, religious and priests. Ukraine

– Catechetical Bureau of the Greek Catholic Church: education programme. – Greek Catholic Church: training of army chaplains. – Environmental Bureau of the Greek Catholic Church: education programme. – Management training programme for school directors. – 6th Ecumenical Social Week for the promotion of the Catholic social doctrine. The total amount of grants-in-aid was slightly over € 110,000.

* A representative sample.

-

7F o u n d a t i o n C o m m u n i C a n t e s ◆ a n n u a l r e p o r t 2 0 1 3

Catholic social thinking should be their preferred multi-tool.

In the same time, Pope John Paul ii insisted, Catholics are called to dialogue and exchange, which are means to create a greater unity among all people of good will in Europe. Thus, the Christian voice may sound more eloquently and more convincingly. However, this conversation about themes like war and peace, recon-ciliation or welfare state is not limited to the ecumenical and interreligious dia-logue but includes nonbelievers as well.

The quest for Europe is closely related to the question of Catholic or Christian identity. If we ask ourselves, how we as

Christians may contribute to Europe we must ask ourselves, of course, what Eu-rope means to us. This, however, is a re-flexive question, which points back at us. Because Christianity grew up in Europe and because we are very much a part of Europe ourselves, we must ask: Who are we as Catholics, as Christians?

Our aim is to facilitate a well-informed and active discussion. We want to invite believers, who take an interest in issues surrounding the relation between Church and society, Church and world. They may be active as professional at uni-versity, in a church organisation or as volunteer.

This was a deliberate choice, which explains why the focus of our Commu-nicantes 2.0 programme is not limited to intellectual exchange. The spiritual di-mension and the way in which ideas and inspiration are put into practice will re-ceive broad attention as well. Head, hart and hands are our focal points.

This programme should last for one year at the end of which three things should have become clear. 1. The indis-soluble connection between Europe and Christianity. 2. The reality that different confessions and regions (East and West) give distinctive sometimes contrasting answers to how that connection should look like. 3. How responsibilty is trans-formed into concrete action.

Hopefully, at the end of this sum-mer, we have a clear idea of what theme we will discuss, how and with whom.

Constructief en wederzijds Constructive Collaboration and

Mutual Understanding Konstruktive und wechsel seitige

Verständigung

‘Europe today must not simply appeal to its former Christian heritage: it needs to be able to decide about its future in conformity with the person and mes-sage of Jesus Christ.’ Pope John Paul II in ‘Ecclesia de Europa’, nr. 2.

-

8 F o u n d a t i o n C o m m u n i C a n t e s ◆ a n n u a l r e p o r t 2 0 1 3

Goal of CommunicantesSince 1974, the foundation Communicantes has been promoting exchange between Dutch Roman Catholics and believers in Central and Eastern Europe. Acknowledging that these contacts are necessary to express our common Christian faith, our core values re-mained: understanding, respect and dialogue. To achieve its goals Communicantes actively promotes the exchange of believers from East and West and acts as an intermediary be-tween projects from the Roman and Greek Catholic Churches and grant giving charities. Support is mainly directed at activities in the field of pastoral care in its broadest meaning.

Board MembersProfessor N. Schreurs, PresidentFather F. Kuster s.s.s., SecretaryH.A.A. van Bemmelen, TreasurerG. van Dartel M.Div.Father B. Schols s.s.s.Father J. Stuyt s.j. Llm (until 18 October)J. Wortelboer

StaffAdvisor

Paul Wennekes M.Div.Communication and Projects Frans Hoppenbrouwers M.Div.

Contacta Stichting Communicantes

Postbus 6016 5002 aa Tilburg

t 013–5423782e [email protected] www.communicantes.nlr 22.57.912 iban nl58ingb0002257912 bic ingbnl2a

kvk 450.55.777

Independence squarein Kyiv, 11 December 2013.

Protesters resist the Berkut riot police by the force of

the crossalone