α Johann Sebastian Bach - Idagio · 2019. 3. 15. · bwv 1046 est destiné à un important eff...

Transcript of α Johann Sebastian Bach - Idagio · 2019. 3. 15. · bwv 1046 est destiné à un important eff...

-

Johann Sebastian BachConcerts avec plusieurs instruments – VI

Café Zimmermann

α

-

α

-

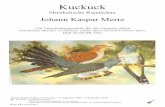

Illustration : Anonyme

Portrait d’une femme tenant une tasse, xviiie siècleHuile sur toile, 81 x 24 cm.

Roubaix, Musée d’Art et d’Industrie

Le commentaire de ce tableau par Denis Grenier est en page 7.

-

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Ouverture n°4 en ré majeur BWV 10691 Ouverture 11’112 Bourrées I & II 2’563 Gavotte 1’454 Menuets I & II 3’205 Réjouissance 2’30 Pablo Valetti premier violon & konzertmeisterAndoni Mercero, Guadalupe Del Moral, David Plantier, Mauro Lopes Ferreira, Maria Gomis violonsPatricia Gagnon, Diane Chmela altosPetr Skalka, Robin Michael violoncellesKate Aldridge contrebasseCéline Frisch clavecinCarles Vallès bassonEmmanuel Laporte, Guillaume Cuiller, Jasu Moisio hautboisHannes Rux, Helen Barsby, Ute Rothkirch trompettesDaniele Schaebe timbales

-

Concerto pour clavecin en la majeur BWV 10556 Allegro 4’037 Larghetto 3’488 Allegro ma non tanto 3’44

Céline Frisch clavecinPablo Valetti premier violon & konzertmeisterDavid Plantier second violonPatricia Gagnon altoPetr Skalka violoncelleKate Aldridge contrebasse

Concert Brandebourgeois n°1 en fa majeur BWV 10469 3’5210 Adagio 3’3411 Allegro 4’0312 Menuet & Polonaise 5’41

Pablo Valetti premier violon & konzertmeisterAndoni Mercero, Nicholas Robinson, Pedro Gandia, David Plantier, Mauro Lopes Ferreira, Maria Gomis violonsPatricia Gagnon, Diane Chmela altosPetr Skalka, Robin Michael violoncelleDavid Sinclair contrebasseCéline Frisch clavecin

-

5

Laurent Le Chenadec bassonEmmanuel Laporte, Jasu Moisio, Gilberto Caserio hautboisThomas Muller, Raul Diaz cors

Concerto pour quatre clavecins en ré mineur BWV 106513 Allegro 3’2514 Adagio 2’0815 Allegro 3’08

Anna Fontana premier clavecin Dirk Boerner deuxième clavecinConstance Boerner troisième clavecinCéline Frisch quatrième clavecin Pablo Valetti premier violon & konzertmeisterDavid Plantier, violon Patrica Gagnon, altoPetr Skalka violoncelleLudek Brany contrebasse

-

Enregistré en février 2004 à L’Arsenal de Metz** & en mars 2010 et mai 2010 au Temple Saint-Jean de Mulhouse

Prise de son & mastering : Hugues Deschaux Direction artistique & montage : Aline BlondiauResponsable de production Alpha : Julien Dubois

Responsable de production Café Zimmermann : Juliette LobryMise en page du livret : Anne Lou Bissières

Photographies : Robin Davies

En résidence au Grand Th éâtre de Provence (Aix-en-Provence), l’Ensemble Café Zimmermann reçoit le soutien du Ministère de la Culture

(Direction Régionale des Aff aires Culturelles)

-

7

AnonymePortrait d’une femme tenant une tasse, xviiie siècle

Huile sur toile, 81 x 64 cmRoubaix, Musée d’Art et d’Industrie

Représentée de face en léger trois-quarts, assise sur un fauteuil dont le dossier recouvert d’un tissu aux accents bleu-vert est sculpté de motifs fl oraux dominés par une rose centrale, la dame au maintien distingué regarde le spectateur droit dans les yeux. À sa droite, sur la table en bois ouvragé, surmontée d’un dessus en marbre turquoise, sont posés cafetière en argent au refl et stanneux et sucrier en porcelaine chinoise. Le précieux liquide vient d’être versé dans la tasse aux motifs fl oraux d’un même esprit ; surprise par le regard « intrus », elle s’apprête à l’agiter pour faire fondre le sucre qu’elle y a ajouté à l’aide d’une petite cuillère en vermeil. Retenue par un bandeau noir, la coiff e aux multiples broderies se marie avec sa chevelure argentée, prolongée par de riches boucles d’oreilles aux gemmes entourées de pierres précieuses. Trois rangs de perles au cou, les yeux vifs, le nez proéminent, et les lèvres esquissant un léger sourire, la dame est vêtue d’une robe au décolleté généreux, agrémentée aux manches de multiples nœuds et rubans, de même que de fi nes dentelles qui se prolongent jusqu’à la taille. Cette tenue recherchée et élégante, cette distinction, marquent le goût de la classe des notables de l’Ancien Régime.

La variété des motifs et textures au rendu exemplaire, d’une perfection qui les fait plus vrais que nature, sans doute un héritage fl amand, ne rompt jamais l’équilibre de la composition dont les diff érents éléments entrent en consonance :

-

8

sous l’abondance se profi le le contrôle de l’artiste, maître de son style et de sa technique, lequel ordonnance leurs interrelations avec sûreté et un certain sens de l’ascèse. Appartenant au même siècle que Jean-Sébastien Bach, sans pour autant s’y rapporter directement, ce tableau peut y être associé ne serait-ce que pour un intérêt pour la structure auquel la France n’est pas étrangère. C’est ainsi que de nombreuses lignes convergeant vers un point central contribuent à unifi er une page qui, malgré un décor élaboré, quoique sans excès, est hiérarchisée dans les moindres détails des plis et replis de la dentelle et des boucles de la coiff e et de la poitrine, cela évoque l’ordre et la rigueur partagés par les deux cultures, française et allemande. Et pour moduler l’eff et sonore du rouge de la robe s’insinuent en se relayant de multiples points de couleur bleutée – tissu du siège, sucrier, tasse – et argentée – cafetière, sucre, rubans et dentelles – notes furtives, subtils échos chromatiques dus au travail d’un orfèvre distribuant avec art « guirlandes » et diamants dans une opulence contenue.

Café ou chocolat ? Le titre demeure muet sur la nature de la boisson dont la forme de l’ustensile ne permet pas de discriminer le contenu. Mais voici que sous les auspices du premier, les musiciens de l’ensemble éponyme s’apprêtent à briser le silence. Énergie, couleurs, miroitements : image et sonorités, tout converge vers une même fi nalité, le plaisir des sens.

© Denis Grenier

ut pictura musicala musique est peinture, la peinture est musique

-

9

Jean-Sébastien Bach. Concerts avec plusieurs instruments, vol. VI

Ouvrant la série des Six Concerts avec plusieurs instruments que Bach, alors au service du prince Leopold d’Anhalt-Coethen, dédie en 1721 au margrave de Brandebourg, grand-oncle du futur Frédéric II de Prusse, le Concerto Brandebourgeois n° 1 bwv 1046 est destiné à un important eff ectif instrumental : deux cors de chasse, trois hautbois et un basson, violon piccolo, deux violons, alto, violoncelle, violone et continuo. Ce que Bach nomme ici « violon piccolo » concertant n’est pas un instrument particulier, mais simplement un violon accordé à la tierce mineure supérieure pour des raisons de sonorité, afi n qu’il se détache mieux des autres. Et pour commencer cette suite de six tableaux évoquant les plaisirs de la cour, voici que le musicien nous invite à participer à une scène de chasse, comme l’indiquent les instruments traditionnellement liés à la nature, les cors, bien sûr, mais aussi les hautbois de la pastorale. On connaît des versions antérieures de certains mouvements de l’œuvre, qui ne s’est constituée qu’au fi l des années. C’est ainsi que le premier morceau, plus ancien, aurait pu servir d’introduction à la cantate « de la chasse », précisément, dès 1713. Dans son état défi nitif, la structure de cette partition amplement développée est très inhabituelle, puisque composée de deux grands blocs, le concerto proprement dit précédant une suite de danses. En trois mouvements contrastés, comme il convient, le concert initial oppose deux morceaux rapides extrêmes, relevant du concerto grosso où dialoguent des groupes instrumentaux, à un ravissant Adagio central faisant dialoguer deux solistes. L’imagination de Bach s’y déploie de toutes parts. C’est, dans le premier Allegro, brillant mouvement avec reprise, la superposition de mètres ternaires

-

10

assénés par les cors sur les mètres binaires des autres instruments, provoquant un joyeux tohu-bohu très savoureux. La ravissante guirlande mélodique ornée de l’Adagio se partage entre premier hautbois et violon piccolo, et c’est ce dernier qui s’approprie la vedette dans le jubilant Allegro, en compagnie d’un premier cor particulièrement virtuose. Le concerto achevé, au retour de la chasse, peut-être, on danse. Ce divertissement est constitué d’un menuet, servant de refrain et encadrant trois couplets, deux trios et une polonaise au centre. L’enchaînement se fait alors très simplement : menuet – trio I – menuet – polonaise – menuet – trio II – menuet. Si le menuet est exécuté par l’ensemble instrumental au complet, les couleurs changent pour les couplets. Le premier trio fait appel aux deux hautbois et au basson sans continuo, c’est-à-dire en formation de plein air, la polonaise au tutti des cordes et du continuo, sans le violon piccolo et dans la nuance piano, le second trio aux deux cors et aux trois hautbois sans continuo. Diversité des coloris, des rythmes, fantaisie le concerto se conclut dans la joie générale.

Comme tous ses contemporains, qu’ils soient musiciens de ville ou de cour, Bach a dû produire de nombreuses Suites. S’il n’en demeure que quatre, on peut penser qu’aussi bien pour la principauté d’Anhalt-Coethen que pour les multiples occasions de fêtes et de cérémonies à Leipzig, le nombre en fut bien plus important. Son ami Telemann n’en a-t-il pas écrit plus de deux cents ? Car non seulement l’époque était friande de ces divertissements, mais ceux-ci avaient surtout le privilège d’évoquer aux oreilles des auditeurs les fastes de Versailles, référence européenne du grand goût. C’est du reste bien ainsi que l’entend Bach, adoptant ici une manière résolument française. Il en bannit l’allemande, et pour éviter tout schéma préétabli, déploie la plus grande liberté dans l’organisation des pièces. La Suite pour orchestre n° 4 en ré majeur bwv 1069 est des quatre la plus opulente par

-

11

son instrumentarium : trois trompettes, timbales, trois hautbois et basson, cordes et continuo. La circonstance pour laquelle elle fut écrite devait appeler un éclat tout particulier, et le musicien mit à profi t les eff ectifs dont il disposait pour écrire sa partition à douze parties réelles. Dans le constant travail de remaniements, de transcriptions et d’adaptations auquel se livre Bach, préoccupé de ne pas laisser disparaître les plus beaux produits de son imagination, il reprend pour le morceau principal, l’Ouverture, les éléments du chœur initial de la cantate Unser Mund sei voll Lachens (Que notre bouche soit emplie de rires) bwv 110, de 1725, lui-même réélaboration d’un original perdu. L’instrumentation vise à varier les coloris, en faisant intervenir les instruments par groupes de timbres. Ainsi s’individualisent le chœur des bois (les trois hautbois et le basson), la fanfare des cuivres avec timbales, et le groupe des cordes, dans des eff ets de polychoralité à la vénitienne. Quant aux deux Menuets, ils ne font appel qu’à des eff ectifs plus modestes, comme il convient à une danse de cour.

L’histoire du Concerto pour clavecin et cordes en la majeur bwv 1053 est celle de remplois et de transformations au fi l du temps, comme il arrive souvent. On ignore tout du concerto d’origine, pour hautbois ou pour fl ûte, remontant très certainement à l’époque de Coethen ; mais on peut aisément le reconstituer à partir de ses remplois ultérieurs. On pense généralement, à juste titre, qu’il s’agissait d’un concerto pour hautbois, et c’est sous cette forme que l’a enregistré l’ensemble Café Zimmermann dans la même collection de Concerts avec plusieurs instruments (volume III, Alpha 071). En eff et, Bach a utilisé plus tard la musique des trois mouvements de ce concerto pour les introduire dans des cantates. Le premier mouvement constitue la vaste et brillante sinfonia introductive de la cantate Gott soll allein mein Herze haben (Dieu seul doit posséder mon cœur) bwv 169, entendue

-

12

le 20 octobre 1726. Et comme toujours, Bach amplifi e, c’est-à-dire que le concerto pour instrument soliste et cordes est devenu un morceau pour orgue et orchestre. Le deuxième mouvement, merveilleuse et si émouvante sicilienne, a également servi à Bach pour constituer l’aria d’alto de cette même cantate. Enfi n, le musicien a repris le troisième mouvement du concerto perdu pour en faire la sinfonia initiale de la cantate en dialogue Ich geh’ und suche mit Verlangen (Je m’en viens plein de ferveur à ta recherche) bwv 49, exécutée le 3 novembre 1726, soit deux semaines seulement après la cantate bwv 169. Sans doute a-t-il été écrasé par le travail en cette période, pour avoir ainsi en si peu de temps réutilisé les trois mouvements de ce concerto. Mais l’histoire ne s’arrête pas là, car plusieurs années plus tard, lorsqu’il produit les concerts du Collegium musicum dont il a repris la direction, il se souvient du concerto pour fl ûte ou hautbois, et le transforme en concerto pour clavecin. Non d’après l’original, mais à partir des transformations opérées pour les cantates, à cela près qu’une fois encore, il amplifi e le discours en enrichissant la texture du morceau. Alors qu’il avait ajouté à l’original trois hautbois dans la sinfonia de la cantate bwv 169, une voix d’alto dans l’aria de la même cantate et un hautbois d’amour dans la sinfonia de la cantate bwv 49, il revient ici à l’eff ectif très réduit des cordes seules, mais certainement dans une réécriture tenant compte des transformations antérieures. Le produit est un pur et admirable concerto pour clavecin et cordes, dont on ne saurait deviner les transformations qui ont présidé à sa rédaction. Œuvre très diversifi ée, où la sicilienne médiane contraste avec l’entrain du premier mouvement, et plus encore l’énergie de l’Allegro fi nal.

Devant l’ampleur de la tâche qu’il avait à aff ronter, d’assurer chaque semaine un nouveau programme de concert, Bach a très certainement fait jouer des œuvres de ses collègues – et il ne manquait pas de concertos ni de suites, à l’époque ! –,

-

13

de même qu’il a pratiqué des transcriptions et adaptations, de ses propres œuvres comme de celles de ses contemporains. Le Concerto pour quatre clavecins et cordes en la mineur bwv 1065 en est l’un des exemples les plus frappants, puisqu’il s’agit d’une adaptation, réalisée vers 1730, donc dans les premiers mois de direction du Collegium Musicum, du Concerto pour quatre violons et cordes en si mineur op. III n° 10 de Vivaldi. Ce concerto fait partie de l’admirable recueil de L’Estro armonico, publié à Amsterdam en 1711, qui avait fasciné Bach au point d’en avoir déjà transcrit cinq autres concertos quelque quinze ou vingt ans auparavant. Forkel, le premier biographe de Bach, qui en a lu la partition, indique qu’il n’a pas pu juger de l’eff et produit, « n’ayant jamais été dans le cas de réunir dans ce but quatre instruments et quatre artistes pour le jouer ». Il est vrai que Bach avait sous la main un bataillon de clavecinistes aguerris, en la personne de ses trois fi ls aînés et des meilleurs de ses élèves. Sans doute exécuté au Café Zimmermann, ce concerto à l’eff ectif si extraordinaire – quatre clavecins brasillant de tous leurs feux ! – dut rencontrer un vif succès auprès des auditeurs, puisque l’on en connaît de nombreuses copies anciennes. Loin de l’original pour instruments à cordes, la nouvelle version de Bach fait miroiter une polyphonie étincelante avec un très léger soutien instrumental, dans un climat qui conjugue à la fois la transparence et la densité. Un chef-d’œuvre !

Gilles Cantagrel

-

1414

Anonymous (18th century)

Portrait of a Woman Holding a CupOil on canvas, 81 x 64 cm

Roubaix, Musée d’Art et d’Industrie

Seated in an armchair upholstered in blue-green fabric, its back carved with fl oral motifs and dominated by a central rose, the lady of distinguished bearing is portrayed full-face, turning slightly and looking the viewer straight in the eye. To her right, on the carved wooden table surmounted by a turquoise marble top stand a silver coff ee pot with a stannous refl ection and a sugar bowl in Chinese porcelain. Th e precious beverage has just been poured in a cup with fl oral decoration in the same spirit. Surprised by the ‘intrusive’ gaze, she is about to stir it with a small vermeil spoon to dissolve the sugar that she has added. Held a black bandeau, the embroidered headdress blends with her silvery hair. Bedecked by rich jewelled earrings and three strands of pearls round her neck, the lady’s face features lively eyes, a prominent nose and a faint smile on her lips. Her refi ned, elegant dress with its generous décolletage, sleeves embellished with multiple bows and ribbons similar to the fi ne lace cascading to the waist, and her distinction mark the taste of the class of notables under the Ancien Régime.

Th e exemplary perfection in the rendering of the variety of patterns and textures—doubtless a Flemish heritage—makes them seem more than lifelike and never breaks the balance of the composition of which the diff erent elements harmonise. Under the abundance, the artist’s control emerges, displaying the mastery of style and technique and organising their interrelations with sureness and

-

1515

a certain sense of asceticism. Belonging to the same century as Johann Sebastian Bach without, for all that, relating directly to it, this painting can be associated with it were it only for the interest in structure, which was not unfamiliar to France. So it is that numerous lines converging on a central point contribute to unifying the image and evoking the order and rigour shared by both French and German cultures. For, despite an elaborate decor—albeit without excess—, everything is organised in a hierarchy down to the slightest detail of the many folds of the lace and the loops of the headdress and bust. And to modulate the sonorous eff ect of the redness of the dress, multiple spots of blue (the fabric of the seat, sugar bowl, cup) and silver (coff ee pot, sugar, ribbons and lace) creep in, relaying each other: furtive notes, subtle chromatic echoes due to the work of an expert artfully distributing ‘garlands’ and diamonds in restrained opulence.

Coff ee or chocolate? Th e title gives no clue as to the nature of the beverage, nor does the cup allow for distinguishing the contents. But here, under the auspices of the former, the musicians of Café Zimmermann prepare to break the silence. Energy, shiammering colours, image and sounds; everything converges to the same end: the pleasure of the senses.

© Denis GrenierTranslated by John Tyler Tuttle

ut pictura musicamusic is painting, painting is music

-

16

Johann Sebastian Bach Concerts avec plusieurs instruments, vol. VI

Opening the set of six Concerts avec plusieurs instruments that Bach, then in the service of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Coethen, dedicated in 1721 to the Margrave of Brandenburg, great-uncle of the future Frederick II of Prussia, Brandenburg Concerto no. 1 BWV 1046 is scored for a large ensemble: two natural horns, three oboes and a bassoon, a violino piccolo, two violins, viola, cello, violone and continuo. Th e violino piccolo concertato specifi ed by Bach is simply a small violin tuned a minor third above standard violin tuning to make it stand out better. And to begin this set of six concertos evoking the pleasures of the court, the composer conjures up a hunt, using instruments traditionally associated with nature, the horns, of course, but also the oboes of the pastorale. Th is work was put together over several years, and earlier versions of some of the movements are known. Th e fi rst one, for example, which is older than the others, is believed to have been composed as an introductory sinfonia to bwv 208, the Hunt Cantata, of 1713. In its defi nitive state, the structure of this generously developed score is very unusual in that it consists of two large blocks: the concerto itself, then a dance suite. Th e initial concert is appropriately in three contrasting movements, fast–slow–fast, as in the concerto grosso, with the instrumental groups conversing in the fast outer movements and two soloists in dialogue in the delightful central Adagio. Bach’s imagination here is extremely fertile. In the opening Allegro, a brilliant movement with reprise, the ternary metres of the horns are superimposed on the binary metres of the other instruments, resulting in a delightful and joyous pandemonium. Th e ravishing ornamented melody of the Adagio is shared between the fi rst oboe and the violino piccolo, before the latter takes the star role in the jubilant Allegro, in

-

17

the company of a particularly virtuosic principal horn. After the hunt comes the dancing. Th e last movement consists of a Menuet, serving as a refrain, framing three contrasting episodes (two Trios and a central Polonaise), which gives the following sequence: Menuet—Trio I—Menuet—Polonaise—Menuet—Trio II—Menuet. Th e Menuet is performed by the full instrumental ensemble, with the colours changing for the episodes. Trio I is for two oboes and bassoon without continuo (out-of-doors atmosphere); the Polonaiseis taken by the strings and continuo, without the violino piccolo and in the piano dynamic; Trio II is taken by the two horns and three oboes without continuo. Th e concerto, characterised by diversity, in its colours, rhythms and imaginativeness, ends in general rejoicing.

Like all musicians of his time, whether employed by a city or by a court, Bach had to produce many suites. Only four are extant, but he must have composed many more than that, not only for the principality of Anhalt-Coethen, but also for the countless celebrations and ceremonies that took place in Leipzig. Did not his friend Georg Philipp Telemann write over two hundred such compositions? Entertainments such as that were very popular during that period; furthermore, they evoked for listeners the pomp of Versailles, which was then the European reference in matters of taste. And so we fi nd Bach adopting a decidedly French manner. He banished the German style, and avoiding any pre-established pattern, showed the greatest freedom in his arrangement of the pieces. Th e Orchestral Suite no. 4 in D major BWV 1069 is the richest of the four in the instruments employed: three trumpets, timpani, three oboes and bassoon, strings and continuo. It must have been written for an occasion that required particular splendour, and Bach took advantage of the forces available to him to score it for twelve real parts. In the constant reworking, transcribing and adapting in which Bach engaged in order to

-

18

ensure that his fi nest creations lived on, he took up for the main piece, the Overture, the elements of the opening chorus of his cantata Unser Mund sei voll Lachens bwv 110 of 1725, itself a reworking of a lost original. Th e instrumentation aims to vary the colours by grouping the instruments by timbre: chorus of woodwinds (the three oboes and the bassoon), fanfare of brass instruments with timpani, group of strings. Th ese are individualised by the use of Venetian-style polychoral eff ects. As for the two Minuets, they require smaller forces, as befi ts a court dance.

Th e history of the Concerto for harpsichord, strings and continuo in E major BWV 1053 is one of reuse and transformation over time, as is often the case in Bach’s works. Nothing is known of the original concerto, for oboe or fl ute, almost certainly dating from Bach’s years at Coethen, but it can easily be pieced together from subsequent reuses. It is generally believed that it was an oboe concerto, and the ensemble Café Zimmermann recorded it in that form in this same series (Volume III Alpha 071). Bach later used the music of the three movements of that concerto in cantatas. Th e fi rst movement is the vast and brilliant introductory sinfonia of the cantata Gott soll allein mein Herze haben bwv 169, which was heard on 20 October 1726. As usual, Bach amplifi es the original piece, with the concerto for solo instrument and strings becoming a composition for organ and orchestra. Th e second movement, a marvellous and very moving Siciliano, was used by Bach as the alto aria in the same cantata, bwv 169. Finally, he took the third movement of the lost concerto for the opening sinfonia of the dialogue cantata Ich geh’ und suche mit Verlangen bwv 49, which was performed on 3 November 1726, two weeks after bwv 169. Bach must have been really inundated with work during that period to have reused the three movements of this concerto within such a short space of time. But that is not the end of the story: several years later, when

-

19

he produced the concerts of the Collegium Musicum, of which he took over the leadership, he remembered the concerto for fl ute or oboe, and turned it into a harpsichord concerto, taking as his basis not the original, but the versions found in the cantatas, once again amplifying the discourse by enriching the texture of the piece. Whereas he had added, to the original three oboes of the sinfonia of bwv 169, an alto voice in the aria of the same cantata, and an oboe d’amore in the sinfonia of Cantata bwv 49, he returns here to the very small forces of strings alone, while no doubt taking into account previous transformations. Th e result is an admirably pure concerto for harpsichord and strings that does not betray the transformations that led to its existence. Th is is a very diversifi ed work, in which the central Siciliano provides a contrast with the lively fi rst movement, and even more with the energy of the fi nal Allegro.

Given the magnitude of his task in having to provide a new concert programme each week, Bach must have included not only works by his colleagues (there was certainly no lack of concertos or suites at that time!), but also transcriptions and adaptations of his own works and those of his contemporaries. Th e Concerto for four harpsichords, strings and continuo in A minor BWV 1065 is one of the most striking examples, being an adaptation, dating from around 1730 (i.e. during his early months as director of the Collegium Musicum) of Vivaldi’s op. III no. 10, the Concerto for four violins, strings and continuo in B minor, rv 580, from the admirable L’Estro Armonico (Amsterdam, 1711), which had so fascinated Bach that he had already transcribed fi ve concertos from it some fi fteen or twenty years previously. Forkel, Bach’s fi rst biographer, who had read the score, admitted that he was unable to ‘judge the eff ect of this composition, for I have never been able to get together the four instruments and four performers it requires’. Bach on the other

-

20

hand had access to a whole battalion of seasoned harpsichordists, including his three eldest sons and the best of his pupils. Probably performed at Zimmermann’s Coff ee House in Leipzig, this concerto for extraordinary forces—four scintillating harpsichords!—must have been hugely successful, judging by the number of early copies still in existence. Very diff erent from the original for strings, Bach’s new version uses sparkling polyphony with a light instrumental support, in an atmosphere that combines both transparency and density. Th is is a masterpiece!

Gilles Cantagrel

-

21

-

22

Anonymes WerkPorträt einer Frau, eine Tasse haltend, 18. Jahrhundert

Öl auf Leinwand, 81 x 64 cmRoubaix, Musée d’Art et d’Industrie

Die von vorne in angedeuteter Dreiviertelansicht dargestellte Frau sitzt auf einem Sessel, dessen mit blau-grün schimmerndem Stoff bezogene Rückenlehne mit fl oralen Schnitzereien verziert ist; den oberen Abschluss dieser Verzierungen bildet eine Rose. In vornehmer Haltung schaut die Dame den Betrachter direkt an. Zu ihrer Rechten stehen auf einem kunstvoll gearbeiteten Tisch mit türkisfarbener Marmorplatte eine zinnern schimmernde Silberkaff eekanne und eine Zuckerschale aus chinesischem Porzellan. Soeben wurde die kostbare Flüssigkeit in eine mit passenden Blumenmotiven verzierte Tasse gegossen und die vom „ungebetenen“ Blick überraschte Dame schickt sich an, diese nun umzurühren, um den Zucker, den sie hinein gegeben hat, mit Hilfe eines kleinen Löff els aus vergoldetem Silber aufzulösen. Die vielfältig bestickte und von einem schwarzen Band gehaltene Haube harmonisiert mit ihrem silbergrauen Haar, genau wie die mit Edelsteinen besetzten Gemmen-Ohrhänger. Die Dame mit dem lebhaften Blick, einer vorspringenden Nase und einem leichten Lächeln auf den Lippen trägt neben einer dreireihigen Perlenkette um den Hals ein großzügig dekolletiertes Kleid, das an den Ärmeln mit vielfältigen Schleifen und Bändern geschmückt ist, sowie auch mit feinen Spitzen, die bis zur Taille reichen. Die ausgesucht elegante Kleidung und das vornehme Erscheinungsbild repräsentieren den Geschmack der Oberschicht der Notabeln im französischen Ancien Régime.

-

23

Die Vielfalt der Motive und Strukturen in beispielhafter, zweifellos fl ämisch beeinfl usster Wiedergabe, in einer Perfektion, die sie echter als in natura erscheinen lässt, stört nie das Gleichgewicht der Komposition, deren unterschiedliche Elemente miteinander in Einklang treten: Trotz der Fülle bleibt der Bedacht des Künstlers deutlich spürbar, der seinen Stil und seine Technik beherrscht und mit Sicherheit und einem gewissen Sinn für Askese über ihre Beziehung zueinander bestimmt. Dem gleichen Jahrhundert wie Johann Sebastian Bach zugehörend, sich dennoch nicht direkt auf ihn beziehend, kann dieses Gemälde mit ihm assoziiert werden, und sei es nur aus Interesse für eine Struktur, das Frankreich nicht fremd ist. So tragen zahlreiche, in einem zentralen Punkt zusammenlaufende Linien zur Vereinheitlichung eines Bildes bei, das trotz eines ausgefeilten, aber von Überladungen freien Dekors einer Rangordnung folgt, die bis in die kleinsten Details der Falten und Schwünge der Spitzen und Schleifen reicht, von der Haube bis vor die Brust. Dies erinnert an den der deutschen wie der französischen Kultur gemeinsamen Sinn für Ordnung und Strenge. Um den volltönenden Eff ekt der roten Farbe des Kleides zu modulieren, schmeicheln sich im Wechsel verschiedenste bläuliche – Polsterstoff , Zuckerdose, Tasse – und silberne – Kaff eekanne, Zucker, Bänder und Spitze - Farbtupfer ein, fl üchtige Zeichen, subtiler chromatischer Widerhall als Ergebnis der Arbeit eines meisterlichen Könners, der kunstvoll „Girlanden“ und Diamanten in gezügelter Üppigkeit verteilt.

Kaff ee oder Schokolade? Der Titel des Gemäldes schweigt sich über die Natur des Getränkes aus, auch die Form des Gefäßes erlaubt keinen Rückschluss auf seinen Inhalt. Doch unter dem Vorzeichen des Erstgenannten schicken sich die Musiker des gleichnamigen Ensembles an, die Stille zu durchbrechen. Energie,

-

24

Farben, Spiegelungen, Bild und Klänge konvergieren alle zu dem gleichen Ziel, dem Genuss für die Sinne.

© Denis GrenierÜbersetzung aus dem Französischen von Maren Partzsch

und Hilla Maria Heintz

ut pictura musicaMusik ist Malerei, Malerei ist Musik.

-

25

„Concerts Avec plusieurs Instruments“ , CD VI

Das Brandenburgische Konzert Nr. 1 bwv 1046 eröff net die Reihe der Six Concerts avec plusieurs instruments, die Bach 1721, damals im Dienste des Fürsten Leopold von Anhalt-Köthen stehend, dem Markgrafen von Brandenburg, Großonkel des zukünftigen Friedrich II. von Preußen, widmete. Es ist für eine große Besetzung geschrieben: zwei Jagdhörner, drei Oboen und ein Fagott, Violino Piccolo, zwei Violinen, Viola, Violoncello, Violone und Continuo. Was Bach hier als konzertanten Violino piccolo bezeichnet, ist nicht etwa ein besonderes Instrument, sondern lediglich eine Geige, die eine kleine Terz höher gestimmt ist als üblich, um sich durch die veränderte Klangfarbe besser von den anderen Instrumenten abzusetzen. Zu Beginn dieser aus sechs Bildern bestehenden und die Vergnügungen bei Hofe illustrierenden Komposition lädt der Komponist zu einer Jagdszene ein; das „Jagdkolorit“ verleihen die traditionsgemäß mit der Natur in Verbindung gebrachten Instrumente, so natürlich die Hörner, aber auch die Oboen. Man kennt frühere Versionen einiger Sätze des erst im Laufe der Jahre entstandenen Werkes. So kann auch das erste Stück, ein älteres Werk, durchaus als Einleitung für die „Jagdkantate“ bwv 208 gedient haben, und zwar ab 1713. In ihrer endgültigen Fassung ist die Struktur dieser umfassend entwickelten Komposition ganz ungewöhnlich, da sie aus zwei großen Blöcken besteht; das eigentliche Konzert geht einer Tanzsuite voran. In drei wie üblich kontrastierenden Sätzen stellt das Einleitungs-Konzert zwei extrem schnelle Stücke nach der Art des Concerto Grosso mit miteinander im Dialog stehenden Instrumentalgruppen einem bezaubernden mittleren Adagio gegenüber, in dem erste Oboe und Solovioline im Zwiegesang miteinander konzertieren. Bachs Einfallsreichtum hat sich hier ausgiebig entfalten

-

26

können. Im ersten Allegro, einem glanzvollen Satz mit Reprise, überlagern von den Hörnern bestimmte ternäre die binären Takte der anderen Instrumente und sorgen so für ein fröhliches und absolut köstliches Tohuwabohu. Die bezaubernde, melodisch verzierte Girlande des Adagio teilen sich die erste Oboe und der Violino piccolo, dann rückt letzterer in den Mittelpunkt des jubilierenden Allegros, begleitet vom ersten, besonders virtuosen Horn. Nach dem Ausklang des Konzerts wird, vielleicht wie auch bei der Rückkehr von der Jagd, getanzt. Dieses Divertissement besteht aus einem Menuett, das ritornellartig drei Couplets umrahmt, zwei Trios und eine Polonaise im Mittelteil. Der Übergang vollzieht sich dann sehr einfach: Menuett - Trio I - Menuett - Polonaise - Menuett - Trio II - Menuett. Das Menuett wird viermal unverändert vom Tutti gespielt, eine Änderung erfolgt bei den Couplets. Das erste Trio bedient sich der beiden Oboen und des Fagotts ohne Continuo, also in der Besetzung für Freiluftensemble, die Polonaise erklingt im Streicher-Tutti mit dem Continuo ohne den Violino piccolo sowie in dem vorgegebenen piano, und das zweite Trio wird von den beiden Hörnern und den sie begleitenden drei Oboen ohne Continuo gespielt. Mit ganz unterschiedlichen Klangfarben, Rhythmen und mit großem Einfallsreichtum endet das Konzert in fröhlichem Übermut.

Wie all seine Zeitgenossen, ob nun Stadtmusiker oder Hofmusikanten, hat wohl auch Bach viele Suiten komponiert. Obwohl nur vier davon erhalten sind, ist anzunehmen, dass die Anzahl der sowohl für den Dienst im Fürstentum Anhalt-Köthen als auch anlässlich der zahlreichen Feste und Feierlichkeiten in Leipzig komponierten Suiten wesentlich höher anzusetzen ist. Hat nicht Bachs Freund Telemann allein mehr als zweihundert Suiten geschrieben? Man war zu jener Zeit ganz versessen auf diese Divertissements, denn diese hatten vor allem

-

27

den Vorzug, die Zuhörer an Pracht und Prunk von Versailles zu erinnern, der Referenz für den grand goût in Europa schlechthin. Dies ist übrigens auch Bachs Auff assung, denn er vertritt hier ganz entschieden den französischen Stil. Den deutschen verbannt er völlig aus seinen Suiten, und um jeglichen vorgefertigten Schemata zu entgehen, nimmt er sich für die Anordnung der einzelnen Stücke die größtmögliche Freiheit. Die Orchestersuite Nr. 4 in D-Dur bwv 1069 ist von den vieren die aufwendigste aufgrund des dort verwendeten Instrumentariums: drei Trompeten, Kesselpauken, drei Oboen und Fagott, Streicher und Continuo. Der Anlass, für den sie geschrieben wurde, verlangte off ensichtlich eine ganz besondere Prachtentfaltung und der Komponist nutzte die ihm zur Verfügung stehende Orchesterbesetzung, um eine Komposition mit zwölf echten Instrumentalstimmen zu schreiben. Während der Überarbeitungen, Transkriptionen und Adaptationen, die Bach unablässig vornimmt, um zu vermeiden, dass die schönsten Ergebnisse seines Schaff ens verloren gehen, übernimmt er für den Hauptteil, die Ouvertüre, die Elemente des Einleitungschors der 1725 verfassten Kantate Unser Mund sei voll Lachens bwv 110; dieser Chor ist selbst schon die Nachschöpfung eines verschollenen Originals. Die Orchestrierung zielt darauf ab, die Klangfarben zu variieren, indem die Instrumente nach Klanggruppen eingesetzt werden. So treten der Chor der Holzblasinstrumente (die drei Oboen und das Fagott), die Gruppe der Blechbläser mit den Pauken und die Streicher mit mehrchörigem Eff ekt im venezianischen Stil eigenständig hervor. Die beiden Menuette setzen nur kleiner besetzte Ensembles ein, wie es sich für einen höfi schen Tanz gehört.

Die Entstehungsgeschichte des Cembalokonzertes in A-Dur bwv 1053 legt Wiederverwertungen und im Laufe der Zeit vorgenommene Umgestaltungen nahe, wie dies häufi g geschieht. Es ist nichts über die Urfassung als originales

-

28

Oboen- oder Flötenkonzert bekannt, das mit großer Sicherheit auf die Zeit in Köthen zurückgeht, aber man kann dies leicht rekonstruieren mithilfe späterer Wiederverwendungen. Es wird allgemein und zwar zu Recht angenommen, dass es sich um ein Solokonzert für Oboe handelte; in dieser Form hat es das Ensemble Café Zimmermann im Rahmen der Reihe der Concerts avec plusieurs instruments (CD III, Alpha 071) aufgenommen. Tatsächlich hat Bach später die drei Sätze dieses Konzertes benutzt, um sie in Kantaten einzufügen. Den ersten Satz bildet die umfangreiche und glanzvolle Einleitungssinfonie der Kantate Gott soll allein mein Herze haben bwv 169, die am 20. Oktober 1726 aufgeführt wurde. Und wie immer erweitert Bach diese Bearbeitung, so dass aus dem Konzert für Solo-Instrumente und Streicher ein Stück für Orgel und Orchester wird. In gleicher Weise hat der zweite Satz, das wunderschöne, ergreifende Siciliano, Bach als Vorlage für die Alt-Arie in der gleichen Kantate gedient. Schließlich benutzte der Komponist den dritten Satz des verloren gegangenen Konzerts, um daraus die Einleitungssinfonie der Dialog-Kantate Ich geh’ und suche mit Verlangen bwv 49 zu machen, die am 3. November 1726 aufgeführt wurde, also nur zwei Wochen nach der Kantate bwv 169. Wahrscheinlich war Bach während dieser Zeit dermaßen mit Arbeit überladen, dass er die drei Sätze dieses Konzerts innerhalb ganz kurzer Zeit wieder verwendete. Aber damit ist die Geschichte noch nicht zu Ende, denn einige Jahre später, als Bach die Konzerte des ihm erneut unter seiner Leitung stehenden Collegium Musicum verantwortet, erinnert er sich an das Konzert für Flöte oder Oboe und schreibt es in ein Cembalokonzert um. Allerdings nicht nach dem Original, sondern nach den Umarbeitungen für die Kantaten, wobei er auch hier den musikalischen Diskurs erweitert, indem er die Textur des Stücks insgesamt bereichert. Während er dem Original in der Sinfonia der Kantate bwv 169 drei

-

29

Oboen hinzugefügt hatte, eine Altstimme in der Arie derselben Kantate und eine Oboe d’amore in der Sinfonia der Kantate bwv 49, kommt er hier auf eine stark reduzierte, reine Streicherbesetzung zurück, aber es handelt sich wahrscheinlich um eine Neuerarbeitung, die vorhergehende Veränderungen einbezieht. Das Ergebnis ist ein echtes und ganz wunderbares Konzert für Cembalo und Streicher, bei dem man die Umänderungen nicht erahnt, die seiner Komposition vorausgingen. Ein breit gefächertes Werk, dessen Siciliano als Mittelteil im Kontrast zu dem temperamentvollen ersten Satz steht und sogar noch stärker zur Dynamik des Schluss-Allegros.

Angesichts des Arbeitspensums, das Bach absolvieren musste, um jede Woche ein neues Konzertprogramm anbieten zu können, hat der Komponist sehr wahrscheinlich auch Werke seiner Kollegen spielen lassen - und zu dieser Zeit mangelte es nicht an Konzerten oder Suiten - ebenso wie er eigene Werke und manche aus der Feder seiner Zeitgenossen umarbeitete oder adaptierte. Das Konzert für vier Cembali und Streicher in a-Moll bwv 1065 ist eins der auff älligsten Beispiele dafür, da es sich um eine Bearbeitung des Concerto für vier Solo-Violinen und Streicher in h-Moll Op. III Nr. 10 von Vivaldi handelt, die er gegen 1730 auff ührte, also in den ersten Monaten seiner Leitung des Collegium Musicum. Dieses Konzert gehört zu der wunderbaren Sammlung L’Estro armonico, die 1711 in Amsterdam veröff entlicht wurde und die Bach so faszinierte, dass er etwa fünfzehn Jahre zuvor bereits fünf andere Konzerte daraus übertrug. Forkel, der erste Bach-Biograph, der die Partitur gelesen hat, vermerkt dazu: „Von der Wirkung dieses Concerts kann ich nicht urtheilen, da es mir nie gelungen ist, vier Instrumente und vier Spieler dazu zusammen zu bringen.“ In der Tat hatte Bach ein Heer bewährter Cembalisten zur Verfügung, nämlich seine drei ältesten Söhne

-

30

und seine besten Schüler. Wahrscheinlich wurde dieses Konzert mit solch einer außergewöhnlichen Besetzung – nämlich vier höchst temperamentvollen Cembali - im Kaff eehaus Zimmermann aufgeführt und es muss bei der Zuhörerschaft großen Erfolg gehabt haben, da unzählige alte Abschriften davon bekannt sind. Weit entfernt vom Original für Saiteninstrumente scheint Bachs neue Fassung eine funkelnde Polyphonie vorzuführen mit einer ganz leichten Instrumental-Stütze; Transparenz und musikalische Dichte gehen hier eine sehr gelungene Verbindung ein. Mit einem Wort: Ein Meisterwerk!

Gilles CantagrelÜbersetzung aus dem Französischen von Gisela Gliem und Hilla Maria Heintz

-

portfolio

www.quodlibet.fr

-

39

-

Alpha 181

-

Production

This is an

http://www.outhere-music.com/

-

Outhere is an independent musical productionand publishing company whose discs are publi-shed under the catalogues Æon, Alpha, Fuga Libera, Outnote, Phi, Ramée, Ricercar and Zig-ZagTerritoires. Each catalogue has its own well defi-ned identity. Our discs and our digital productscover a repertoire ranging from ancient and clas-sical to contemporary, jazz and world music. Ouraim is to serve the music by a relentless pursuit ofthe highest artistic standards for each single pro-duction, not only for the recording, but also in theeditorial work, texts and graphical presentation. Welike to uncover new repertoire or to bring a strongpersonal touch to each performance of knownworks. We work with established artists but also invest in the development of young talent. The acclaim of our labels with the public and the pressis based on our relentless commitment to quality. Outhere produces more than 100 CDs per year, distributed in over 40 countries. Outhere is locatedin Brussels and Paris.

The labels of the Outhere Group:

At the cutting edge of contemporary and medieval music

30 years of discovery of ancient and baroque repertoires with star performers

Gems, simply gems

From Bach to the future…

A new look at modern jazz

Philippe Herreweghe’sown label

Discovering new French talents

The most acclaimed and elegant Baroque label

Full catalogue available here

Full catalogue available here

Full catalogue available here

Full catalogue available here

Full catalogue available here

Full catalogue available here

Full catalogue available here

http://world.idolweb.fr/aeon/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/ricercar/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/fuga-libera/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/alpha/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/outnote-records/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/zig-zag-territoires/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/phi/releases.htmlhttp://www.outhere-music.com/www.aeon.frwww.ricercar.behttp://www.outhere-music.com/rameewww.fugalibera.comhttp://www.outhere-music.com/alphahttp://www.outhere-music.com/outnotehttp://www.outhere-music.com/zigzag

-

Here are some recent releases…

Click here for more info

http://world.idolweb.fr/aeon/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/aeon/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/alpha/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/alpha/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/zig-zag-territoires/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/fuga-libera/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/fuga-libera/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/outnote-records/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/outnote-records/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/phi/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/ricercar/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/ricercar/releases.htmlhttp://world.idolweb.fr/zig-zag-territoires/releases.htmlhttp://www.outhere-music.com/http://www.idolweb.fr/http://www.outhere-music.com/