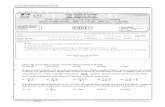

ΕΡΓΑΣΙΑ Greek-Nat-Report-ENG

Transcript of ΕΡΓΑΣΙΑ Greek-Nat-Report-ENG

Preventive Medicine & Nutrition Clinic

Faculty of Medicine University of Crete

Greece

PORGROW NE S T I N SI G H T

PorGrow

A NEST insight EU Project

PPoolliiccyy OOppttiioonnss ffoorr RReessppoonnddiinngg ttoo tthhee

GGRROOWWiinngg cchhaalllleennggee ooff oobbeessiittyy

…….. …….... ……..

GGrreeeekk NNaattiioonnaall RReeppoorrtt

Prepared by:

Caroline CODRINGTON

Katerina SARRI

Anthony KAFATOS

Preventive Medicine & Nutrition Clinic

Faculty of Medicine - University of Crete

PO Box: 2208

Greece

http://nutrition.med.uoc.gr

Acknowledgements The Greek research team of the PorGrow project would like to thank all the

participants who were interviewed and generously gave their time to the project. We

are equally grateful to the team of SPRU, University of Sussex, UK and especially

Professor Erik Millstone and Professor Andy Stirling for their support and guidance

throughout the project.

Disclaimer The results discussed in this report represent the individual points of view of those

interviewed. They are presented in a format that is true to the Multi Criteria Mapping

methodology, and are therefore a consequence of this method, including its

constraints. These results cannot therefore be taken as representing the official

positions of the institutions, organisations or associations in which the individuals

interviewed work.

CONTENTS Executive Summary Section 1 Epidemic of obesity ………………………………………………………………1

1.1 Overweight and Obesity in Adults 1.1.1 Criteria 1.1.2 Prevalence 1.1.3 Age-related prevalence 1.1.4 Severity 1.1.5 Sociodemographic characteristics 1.1.6 Secular trends 1.1.7 Interpretation 1.2 Overweight and Obesity in Children 1.2.1 Prevalence 1.3 Conclusion

Section 2 Estimated Costs of Obesity………………………………..……….…………..….12

2.1 Human Costs: Health Risks and the Burden of Disease 2.2 Morbidity and Mortality in Greece 2.3 Health Care Costs 2.4 Other Economic Costs 2.5 Conclusion

Section 3 Trends in food consumption and physical activity…………………..………..23

3.1 Causal Influences 3.2 Trends in food consumption

3.2.1 Changing food patterns 3.2.2 Shifting dietary habits 3.2.3 Past and Present

3.3 Physical Activity 3.3.1 Patterns of Activity : Adults 3.3.2 Patterns of Activity : Children and Adolescents

3.4 Concluding Comments Section 4 Policy-making institutional structures…………………..………………………36

4.1 Health 4.1.1 Health Care 4.1.2 Public Health

4.2 Food 4.3 Physical Activity 4.4 Concluding Comment

Section 5 Policy debates and initiatives……………………………………………………..42

5.1 Policy commitments 5.2 Policy options 5.3 Initiatives 5.4 Scope and receptivity 5.5 Concluding comments

Section 6 Multi-Criteria Mapping: a Methodology………………………………………47

6.1 Introduction to MCM 6.2 Elicitation framework 6.2.1 Recruiting participants and scoping 6.2.2 The MCM interview

6.3 Methods of Analysis Section 7 Stakeholders and their Perspectives………………………………………….….54

7.1 Deciding which stakeholders or participants to include 7.2 Grouping participants into Perspectives 7.3 Greek participants

Section 8 Options for Addressing Obesity………………………………………………….59 8.1 Introduction 8.2 Scope of Process and Definition of Options

8.2.1 Core Options 8.2.2 Discretionary Options

8.3 Clusters of Options 8.4 Engagement with Predefined Options 8.5 Engagement with Additional Options 8.6 Reactions in Predefined Options

8.6.1 Core Options 8.6.2 Discretionary Options

Section 9 Developing criteria ……………………………………………………….………..79 9.1 Introduction

9.1.1 Principles 9.2 Review of the Criteria

9.2.1 Nuances in the use of criteria 9.3 Grouping of Criteria into Issues 9.4 Weighting process Section 10 Appraising option performance (scoring) ……………………………………...93 10.1 Introduction 10.2 Eliciting scores for options 10.3 Appraisal of options by Issues (groups of criteria)

10.3.1 Societal benefits 10.3.2 Extra health benefits

10.3.3 Efficacy in addressing obesity 10.3.4 Economic impact on public sector 10.3.5 Economic cost to individuals

10.3.6 Economic cost to commercial sector 10.3.7 Economic cost unspecified 10.3.8 Practical feasibility 10.3.9 Social acceptability 10.3.10 Others

10.4 Diversity and uncertainty in option scoring Section 11 Mapping option performance (rankings) …………………………………….113 11.1 Introduction 11.2 The overall picture 11.3 Final mean rankings by Participants and Perspectives 11.3.1 A. Public interest, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) 11.3.2 B. Food chain, large industrial and commercial organisations 11.3.3 C. Small food and fitness commercial organisations 11.3.4 D. Large non-food industrial and commercial organisations 11.3.5 E. Policy-makers 11.3.6 F. Public providers 11.3.7 G. Public health specialists

11.4 Final Rankings by Participants 11.5 Patterns of consensus and diversity

11.5.1 Cluster A. Exercise and physical activity-oriented 11.5.2 Cluster B. Modifying the supply of, and demand for, foodstuffs 11.5.3 Cluster C. Information-related initiatives 11.5.4 Cluster D. Educational and research initiatives 11.5.5 Cluster E. Technological innovation 11.5.6 Cluster F. Institutional reforms 11.6 Conclusions Section 12 Process Evaluation……………………………………………………………..….127 12.1 Evaluation process and Results 12.2 Critical Reflections

12.3 Implications for Policy 12.4 Conclusions

Appendices…………………………………………………………………………………………...132 References……………………………………………………………………………………………137

Executive Summary Rising trends in the prevalence of overweight and obesity worldwide are regarded by the World Health Organization (WHO) as posing ‘one of the greatest public health challenges for the 21st century’ (WHO 2005). It is estimated that overweight (including obesity) affects between 25-75% of the adult population in the WHO European Region. Accumulating evidence, albeit much of it fragmentary, indicates that trends in overweight and obesity among children parallel the global ‘obesity epidemic’ among adults. Within this overall picture the situation in Greece looks particularly alarming. Conservative estimates are that 1 in 5 men and 1 in 6 women in Greece are obese and, in addition, that approximately half the men and one-third of the women in Greece are overweight. For children, consistent evidence points to a pattern of high and rising rates of overweight and obesity starting in infancy. As the prevalence of overweight and obesity increases, concern about the association with morbidity and premature mortality is also increasing. Estimates of the burden of disease due to obesity and the related direct and indirect economic costs are focusing attention on obesity as a public health problem requiring the attention of policy makers and health planners, rather than simply the concern of the individuals affected. Reliable estimates of the current and projected economic and health costs of obesity in Greece are needed to inform policy actions. As it stands, the population health profile of relative longevity and low rates of non-communicable diseases has co-existed paradoxically with the rising prevalence of obesity. However, recent trends in morbidity and mortality data particularly for cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes indicates that this pattern no longer holds. Rising morbidity rates associated with obesity and related diseases have been accompanied by escalating health care costs.

Trends towards more energy dense diets and sedentary lifestyles which are driving the obesity epidemic are as apparent in Greece as elsewhere in Europe. Explanations lie in the complex economic and social developments affecting behavioural patterns of communities over recent decades. These processes are dynamic and ongoing, and require substantial changes in public health strategies. Traditional approaches to preventing and treating obesity have almost invariably focused on changing the behaviour of individuals, but the escalating trend in obesity is poignant testimony to the inadequacy of this approach. There is now a broader consensus that reversing current obesity trends will require a better balance between individual and population-wide approaches and between education-based and multi-sectoral environmental interventions (WHO, 2003). National and local governments and relevant international organisations are being called upon to respond with appropriate actions and collaborations to counteract the rising prevalence of obesity. Addressing obesity is a priority of the EU’s Public Health Action Programme for 2003–2008. Identification and support of effective strategies against obesity is an important prerequisite for community action. A wide range of different kinds of interventions could be attempted to influence different aspects of the production and consumption of foods and levels of physical activity. A single uniform combination of policy options would not be expected to be appropriate for both genders, for different age and social groups, or in different countries. The aims of the PorGrow project were, therefore, the exploration of the consistency and/or variability of the perspectives of key stakeholders towards a range of different options to respond to the growing challenge of obesity, and the cross-national comparison of these perspectives between nine participating member states (Cyprus, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Spain and the UK). A novel and powerful technique called Multi Criteria Mapping

has been used to provide an integrative and comparative analysis of the different perspectives of key stakeholders in nine member states on a broad range of possible types of interventions. This report deals with findings at the national level in Greece; a report on cross-national findings between nine participating member states will follow. The PorGrow project conducted a systematic process to identify key public policy options that might have a bearing on how to respond to the rising trend in the incidence of obesity in Greece. Using a Multi Criteria Mapping (MCM) method, quantitative and qualitative data were gathered from representatives of 20 types of organisations representing relevant stakeholder interest groups. During structured interviews, stakeholders were invited to appraise a set of policy options by reference to criteria of their own choosing. They were also invited to provide relative weight to their criteria, and to provide overall rankings of the policy options in relation to each other. The research team then analysed the data gathered in the interviews, and set the results in the context of the rising incidence of obesity in Greece, the changing patterns of food consumption and physical activity, and the current level of debate about policy responses to obesity in Greece. Participants were asked to compare the performance of seven ‘core’ policy options and up to 13 ‘discretionary’ options. They could also introduce their own ‘additional’ policy options. To appraise these options, participants defined criteria, that is, the factors that they will take into account when evaluating those options. Participants judged the performance of each chosen option against each of their criteria; they assigned a score for every option under each criterion using a linear ordinal scale of their own choosing. The higher the score the more optimistic the performance of the appraised option. Participants were invited to score each option using each criterion by reference to both optimistic and pessimistic assumptions, and to make those assumptions explicit. As a final step, participants weighted the criteria in order of their relative importance. In this process, participants scored and ranked the options in terms of their relative performance against a weighted sum of their criteria. Using a simple formula, the scores under each criterion are multiplied by the criteria weightings to produce overall pessimistic and optimistic relative rankings for all the options.

Multi-criteria mapping is not a procedure that can generate a proven recipe of effectiveness, but it does nonetheless provide a formula with which the challenges of obesity can sensibly be approached. The data gathered in this study, when analyzed in the context of rising prevalence of obesity in Greece, the dominant causes and consequences and the existing policy framework, indicate a critical gap between need and response. We found a broad consensus among the stakeholder representatives who participated in the PORGrow study in Greece that an integrated strategy incorporating a number of policy options would be necessary to bridge this gap. We found a broad favourable pre-disposition to implementing measures geared to (a) improving levels of knowledge and understanding about food, diet, health and fitness and (b) for increasing opportunities and incentives for physical activity, with particular support for policies targeting the young. Although not generally supported, there was also significant advocacy by a few for the creation of a new government body charged with inter-sectoral policy co-ordination. Educational options were considered the starting point for all the other options, with initiatives targeting food and health education in schools in particular being the most favoured option. In the cluster of information-related initiatives, mandatory nutrition labelling and controls on food and drink advertising to children were ranked very poorly by the food industry and the advertising industry representatives, but were more optimistically evaluated by the other participants. Physical activity oriented options were widely supported and appraised with optimism. Changes to town planning and transport policies were considered by most to be significant long-term policies, but ranked very low primarily due to perceived

feasibility and cost constraints. By contrast there was considerable support for improvement in communal sports facilities Perhaps reflecting the relatively muted level of debate to date in Greece, in this enquiry we mapped consistently high rankings overall for the more classic policy options directed ‘downstream’, offering individuals the skills, information and opportunities to make healthier lifestyle choices, rather than options geared to modifying the environment to prevent obesity. These options are familiar, relatively low cost, and likely to have social and health-related benefits independent of their effects on obesity issues. By contrast: - CAP, when commented on at all, tended to be viewed as a given environmental/ institutional constraint and reforms were not considered to be relevant to tackling obesity issues. - Controls on food composition were the most widely favoured in the cluster of options aimed at modifying the supply of and demand for foodstuffs. This was, however, most frequently commented on from a food safety perspective rather than in relation to the obesity- or health- promoting properties of ingredients in processed foods. - In a similar vein, ‘technical fix’ options for tackling obesity (increased use of synthetic sweeteners and fat substitutes, medication to control weight) received scant attention and, when commented on at all, were not considered relevant. - Controls on food supplies through controlling sales of food in public institutions met with mixed evaluations, primarily in terms of social acceptability and efficacy. - Fiscal measures (taxes and subsidies) designed to modify consumer buying behaviour were poorly evaluated by most participants also on the grounds of social acceptability and also efficacy. Pricing tactics were considered to have a very low impact on peoples’ dietary patterns and lifestyle choices. In conclusion: in Greece the case for action on obesity as a public health concern is only now being made, the level of debate on policy options is muted to date, and obesity is incidental to the public health agenda and institutional reforms recently initiated. On a more optimistic note, there are signs that the accelerating momentum concerning policy responses at a European level is meeting with a response in Greece. The considered opinions of experts, stakeholders and policy-makers are critical in informing decision-making on appropriate policy responses to obesity. As such the MCM method provides a novel means of capturing and comparing these evaluations. The PorGrow analyses thus point to support for a portfolio of measures to combat the problem of obesity in Greece as well as an appreciation that political will is an essential pre-requisite.

1

Section 1 Epidemic of Obesity Rising trends in the prevalence of overweight and obesity worldwide are regarded by the World Health Organization (WHO) as posing ‘one of the greatest public health challenges for the 21st century’ (WHO 2005). It is estimated that overweight (including obesity) affects between 25-75% of the adult population in the WHO European Region. Accumulating evidence, albeit much of it fragmentary, indicates that trends in overweight and obesity among children parallel the global ‘obesity epidemic’ among adults (WHO 2000). Within this overall picture the situation in Greece looks particularly alarming, with prevalence rates for overweight and obesity which top the charts in international and European ‘league tables’ for both adults and children. Recent high profile publications for the EU Platform for Action on Diet, Physical Activity and Health (IOTF/IASO 2005) and the European Commission’s Green Paper (2005) show a prevalence of overweight and obesity among men (78.6%) and women (74.7%) in Greece which is the highest reported for all 25 EU countries. Greek children and teenagers share a similar dubious distinction, reported as having among the highest rates of overweight and obesity (over 30%) compared with children in other European countries (ibid). International comparisons such as these are invaluable in focusing attention on the serious nature of the problem in Greece. A basic limitation is, however, that these league tables are generated using surveys of various designs, periods, and methods.1 Indeed, the WHO and the IOTF have highlighted the lack of nationally representative data in many countries as a major obstacle to a more accurate assessment of the scale and trends of the obesity epidemic (WHO 2000; IOTF 2005). For Greece, there is no nationally representative survey data equivalent to the US NHANES or the UK regional surveys (England, Scotland, Wales, and N. Ireland). Estimates of the prevalence of overweight and obesity in the Greek population therefore rely on unofficial sources, primarily surveys reported in scientific journals. The reliability, validity and comparability of existing prevalence data for Greece are thus complicated by heterogeneous study designs, differences in the survey populations and, critically, by whether the BMI calculations (see box) were based on self-reported weight and height data or obtained through direct physical examination. Self-reported height and weight data are valid for identifying relationships in epidemiological studies but, particularly where no validity sub-study has been conducted, are liable to underestimate the problem (Spencer et al. 2002; Brener et al 2003; Gillum & Sempos, 2005). We review here the data available for assessing the prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity among adults and children in Greece.

1 The IOTF clearly states these limitations in all publications and underlines the point that with the limited data available, prevalence rates are not standardized. Unfortunately this cautionary note on interpretation is rarely reproduced in press reports or in secondary citations in scientific papers.

2

1.1 Overweight and Obesity in Adults 1.1.1 Criteria Obesity is defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation to the extent that health may be impaired (WHO). Various measures are used to estimate overweight and obesity, with corresponding threshold values calculated to reflect adiposity and to be related to morbidity outcomes. For adults, the most common is the Body Mass Index (BMI), which measures weight relative to height (kg/m²). This correlates fairly well with body fat content in adults but it is only an approximation of adiposity, because an adult with high levels of lean (muscle) mass will also have a relatively high BMI score. Various (BMI) cut-off points have been used to classify ‘normal’ and ‘overweight’ or ’moderate obesity’. The most widely used is the classification adopted by the World Health Organization (see box) whereby overweight is defined as BMI ≥25.0-29.9kg/m² and obesity as BMI ≥30 kg/m². These standard definitions are mainly derived from populations of European descent (WHO 2000) and different thresholds have been proposed for other populations (eg for Asian populations the lower threshold of BMI ≥23 is proposed (IOTF 2005). Measures of fat distribution, notably waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio, are used in association with/or instead of BMI because the distribution of fat affects the risks associated with obesity. That is, increases in abdominal fat pose a greater risk to health than increases in fatness elsewhere. These measures of central adiposity (see box) are increasingly being used to calculate the risk of obesity co-morbidities. For survey purposes, however, BMI is the main measure of overweight and obesity currently used (Molarius et al,1999). 1.1.2 Prevalence Figure 1 (Appendix Table 1A) shows the differences in prevalence of overweight and obesity in men and women in Greece as assessed by major national and sub-national/regional surveys conducted after 1990. The widely cited IOTF data for Greece of obesity prevalence of 27.5% in men and 38.1% in women are based on the major survey conducted throughout Greece in the mid-1990s as part of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) (unpublished data). The Greek EPIC cohort comprised healthy volunteers recruited from the general population and intentionally included a high proportion of women; i.e. it was not designed as a nationally representative sample. It does, however, provide the largest available data set

Adiposity classifications for adults

BMI (kg/m²). Underweight <18.5 Normal range 18.5-24.9 Overweight 25.0-29.9 Obese ≥30 Class I Moderately obese 30.0-34.9 Class II Severely obese 35.0-39.9 Class III Morbidly obese ≥40 Central adiposity Men Women Waist circumference (WC) Action level 1 ≥94cm ≥80cm Action level 2 ≥102cm ≥88cm Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) ≥0.95 ≥0.80

3

using direct standardized measures by trained personnel. The picture of epidemic levels of overweight and obesity is documented in published data on mean BMIs for men (28kg/m²) and women (26.5 kg/m² at <45-y rising to a mean BMI >30 kg/m² >45-y) (Trichopoulou et al 2000; Trichopoulou et al 2005). Detailed analyses of prevalence data published for the 50-64y age bracket show results which parallel the overall IOTF estimates, with amazingly high combined overweight and obesity rates of ~ 80% for both men and women, and with the prevalence of obesity being much higher in women (42.6%) than in men (29.9%) (Haftengerger et al. 2002). FIGURE 1: Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adults in Greece according to 4 surveys

Men

0102030405060708090

IOTF ATTICA HMAO Crete

>30 25-29,9

W omen

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

IOTF ATTICA HM AO Cre te

>30 25-29,9

A similar cumulative prevalence of overweight and obesity for men (73%) is reported in the ATTICA survey, a smaller but representative random sample for the Attica region of Greece, including Athens (Panagiotakos et al 2004). For women, however, the ATTICA Study shows a much lower cumulative prevalence of overweight and obesity (46%); a gender difference which is in line with most other European countries. Recent analysis of epidemiological survey data for Crete also show the same gender difference (63% in men compared with 39% in women), but lower prevalence levels of overweight and obesity in adults in this southernmost region of Greece (Linardakis, 2005). Data from a nationwide cross-sectional study conducted by the Hellenic Medical Association for the Obesity (HMAO) have recently been made available (HMAO, 2004). This shows the same pattern of higher cumulative prevalence rates for Greek men (67%) compared with Greek women (48%). The scale of the problem overall is similar to that assessed by the ATTICA Study although it is interesting to note that the prevalence of obesity recorded in the HMAO survey is higher than both the ATTICA and Crete regional studies, even although the HMAO prevalence rates are derived from self-reported anthropometric measurements (HMAO 2006).2 Conversely, Eurostat data for Greece, based on the Eurobarometer self-report surveys, give a significantly different picture of the scale of the problem, underlining the need for caution in interpreting prevalence rates derived from self-reported data. Thus the Eurostat data for Greece for 1996 and for 1998-2001 (BMI ≥27 for between 29-30% of adults in Greece) collated in the same period as the EPIC, ATTICA and HMAO surveys, show

2 This may in part reflect the sampling procedure: the HMAO conducted a school-based national survey to determine obesity prevalence in children, and the adults comprise parents/guardians selected via the school cluster sampling. They were asked to weigh and measure themselves, rather than simply report height and weight.

4

significantly lower prevalence rates even allowing for differences in the Eurostat cut-off points (BMI ≥27kg/m²). It does, however, reflect a similar pattern insofar as the prevalence of overweight among adults in Greece is among the highest in the EU, and well above the EU-15 average. The Eurostat data also show higher prevalence of overweight in men (34.9%) compared with women (29.4%) (Eurostat 2002). 1.1.3 Age-related prevalence Analyses of age-and gender-related prevalence data for the different surveys are shown in Figure 2a-c. These analyses show a similar general pattern whereby BMI increases steadily with age, and the prevalence of obesity is higher in men than in women up until late middle-age (~50-y). Thereafter obesity rates tend to be higher in older women than in older men, and the Greek EPIC and ATTICA data show the upward trend in obesity prevalence peaking at a later age in women. Data from the Greek EPIC cohort show a steady rise in prevalence of obesity among men, peaking in the 55-64y age range (32.7% obese and 51.2% overweight) whereas for women prevalence rates overtake men in the 45-54y age group (37.9% for women compared to 29% for men) and the increasing trend for women peaks in the 65-74y age group (a staggering 53.4% classed as obese and 36% overweight) (Trichopoulos et al 2003). The HMAO survey and the ATTICA survey show a similar pattern, but the ATTICA Study reports significantly lower rates of obesity for both men and women in all age groups, and shows the age-specific peak prevalence of obesity in men between 40-59 years old and in women between 50-59 years old (Panagiotakos et al 2004). 1.1.4 Severity Limited data on the severity of obesity are provided in the ATTICA Study, which show that 16% of men and 11% of women were moderately obese (Class I:BMI 30-34.9 kg/m²), and <1% of men and women were morbidly obese (Class III: BMI ≥40 kg/m²) (Panagiotakos et al 2004). Limited data are also available for central adiposity, which provides a good indication of related morbidity risk. Based on self-reported measurements, the HMAO reports that 54.3 % men and 56.5% women had ‘high’ waist circumference (WC action level 1 >94cm in men & >80cm in women). Cross-sectional analysis of a representative sample of Greek adults (n=9669) designed to assess prevalence of the metabolic syndrome (the MetS-Greece Multicentre study) shows a higher prevalence based on direct measurement: 56.8% of the general population were characterized by abdominal obesity at WC action level 2 (>102cm in men and >88cm in women) (Athyros et al, 2005).

5

FIGURE 2: Prevalence of overweight and obesity in Greek adults by age and gender Fig 2a : Greek EPIC cohort

Men

0102030405060

25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65-74 75+

Overw eight Obese

Women

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65-74 75+

Overw eight Obese

Source:Trichopoulos et al. 2004.

Fig 2b : HMAO

Men

0

10

20

30

40

50

20-30 31-40 41-50 51-60 61-70

Overw eight Obese

Women

0

10

20

30

40

50

20-30 31-40 41-50 51-60 61-70

Overweight Obese

Source: Hellenic Medical Association for Obesity (HMAO)

Fig 2c: The ATTICA Study

Men

0102030

40506070

20-29 30-39 40-49 50-59 >60

Overw eight Obese

Women

010

2030

4050

6070

20-29 30-39 40-49 50-59 >60

Overweight Obese

Source: Panagiotakos et al. 2004 [Data in Appendix Table A2]

6

1.1.5 Socio-demographic characteristics A recent analysis of trends in lifestyle-related risk factors in Europe reported that intra-national differences in certain factors, including obesity, surpass international differences (van der Wilk and Jansen 2005). The WHO (2005) has also reported that obesity and related diseases are among the most unevenly distributed health conditions, and that there is a trend towards increases in differences between social classes. There is, however, a dearth of reliable data to ascertain whether and/or to what extent this applies in Greece. Fragments from available analyses of the distribution of several socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics of survey participants according to their BMI classification has shown inverse associations between obesity status and years of education (Trichopoulou et al 2005) and by socio-economic status (Manios et al 2005). The ATTICA Study has reported urban-rural differences in prevalence rates, but these were no longer significant when the higher prevalence of physically active occupations in the rural areas was taken into account (Panagiotakos, 2004). Albeit varying in size, design and significance, a number of studies document overweight and obesity in particular age groups and occupations (Mamalakis and Kafatos 1996), including military personnel (Mazokopakis et al 2004), and University students (Bertsias et al 2003). Together with localized surveys (Gikas et al 2004), and gender-specific studies (Nassis and Geladas, 2003), these reinforce the observed pattern of high prevalence rates of overweight and obesity among adults in Greece. For religious and ethnic minorities there are no data apart from the MetS-Greece survey, which shows that prevalence of abdominal obesity is higher in Greek Muslims than the general population (63.6% vs 56.8% respectively) (Athyros et al 2005). Apart from indigenous minorities (Muslim, Romany), this lack of documentation is of particular concern given the burgeoning growth of newly rooted migrant ethnic communities throughout Greece over the last decade. 1.1.6 Secular trends Available data from the Seven Countries Study in the 1960s show the BMIs of middle-aged men were only 22.8 and 23.3 in Crete and Corfu respectively (Dontas et al, 1998). At this stage there were only 2-5% obese men and 20-22% overweight. Low prevalence of obesity was a feature of the Mediterranean region in those years, partly explained by relatively high physical activity levels (Ferro-Luzzi et al 2002). Studies of adults in Crete (Kafatos et al, 1991;1997), and Athens (Moulopoulos 1987) provide benchmarks against which to document the dramatic increase in the prevalence of overweight and obesity. While the data are too limited to determine the precise trajectory of the rising trend, Greece would appear to be well within the WHO observation that the prevalence of obesity has risen three-fold or more in many European countries since the 1980s. The WHO prediction of future trends is not reassuring, estimating that while the prevalence in the European Region is expected to rise by an average of 2.4% in women and 2.2% in men over five years, some countries might show a faster increase – with Greece being listed alongside Finland, Germany, Sweden and the UK as one of the countries where the rate for men can be expected to rise more rapidly (WHO 2005). 1.1.7 Interpretation Interpretation of available prevalence data is complicated and requires caution. Thus, higher prevalence rates of obesity in women compared with men cited in international comparisons (IOTF) is not supported by other available surveys of adults in Greece. Yet this lack of

7

agreement as to gender differences in cumulative prevalence rates may be more apparent than real, the product of differences in study design and the high proportion of older adults in the Greek EPIC cohort (~70% >45y). Similarly, as illustrated in Figure 3, even the same data classified by (slightly) different age-range categories and an extended age range can give a different impression. Such a difference could be critical, for example, if one were looking at policy options targeting older citizens. As it stands, being based on a representative random sample, the relatively conservative prevalence rates reported in the ATTICA Study provide the best available estimate of the current position in Greece: roughly one in five men and one in six women obese. In addition, approximately half of the men and one-third of the women were found to be overweight. Based on the recent (2001 census) age-sex distribution of the Greek population, the ATTICA Study investigators speculated that 2.4 million men and 1.4 million women are overweight, and 900,000 men and 675,000 women are obese (Panagiotakos et al 2004). FIGURE 3: ATTICA Study: prevalence of obesity (BMI≥30 kg/m² ) by age and gender (a) Panagiotakos et. al. 2004 and (b) for WHO Global InfoBase

(a)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

20-29 30-39 40-49 50-59 >60

Men Women

(b)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

18-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65-74 75-89

Men Women

1.2 Overweight and Obesity in Children Studies examining trends in childhood obesity suggest that it has increased steadily in Europe over the past two to three decades (Lobstein et al, 2004). For Greece, there are insufficient data available on temporal changes to date to determine trends. The few longitudinal and cross-sectional regional studies available, however, do indicate that the prevalence of overweight and obesity has been increasing in the last decades, especially among boys (Mamalakis & Kafatos 1996; Mamalakis et al, 2000; Krassas et al 2001; Magkos et al 2005). Recent reports indicate that the prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents in Greece is now among the highest in Europe (IOTF 2005). This is of particular concern given the vast body of evidence which is amassing on the short term health consequences of childhood obesity and the multiple adverse effects tracking through to morbidity and mortality in adulthood (Reilly et al, 2003; Deckelbaum et al, 2001;Engeland et al. 2004; Goran, 2001), in particular the rising rates of type 2 diabetes and other co-morbidities characterizing the metabolic syndrome.

8

Difficulties in assessing prevalence of overweight and obesity in adults are compounded in children by the variations in criteria used. Simple BMI is inappropriate because it does not take into account the changing weight and height in the growth curves of children and adolescents. Various reference values are thus used to define overweight and obesity in children and adolescents. Up until recently, most surveys used the US CDC or NHANES growth charts (which use the 85th and 95th percentiles as the cut-offs for overweight and obesity respectively) and/or population-specific reference values. Since 2000, the age and gender-specific BMI cut-off points adopted by the IOTF of childhood equivalents of overweight (BMI 25-29.9) and obesity (BMI ≥30) in adulthood have been widely used as the best available basis for international comparisons (Cole et al 2000; Lobstein et al 2004). Some caution is necessary in interpreting the terms used for prevalence. Some studies using the IOTF criteria refer to ‘pre-obese’ as the classification of childhood equivalence to BMI 25-29.9 and ‘overweight’ as equivalence to BMI ≥25 (ie including obese BMI ≥30). Unless otherwise stated, this review uses ‘overweight’ to mean BMI 25-29.9.

Waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio are posited as better predictors of obesity co-morbidities in children than BMI (McCarthy & Ashwell 2006; Savvas et al, 2000.) but there are no standard cut-off points currently in use and the data is relatively scarce.

1.2.1 Prevalence The WHO collaborative survey ‘Health Behaviour in School-aged Children’ (HBSC) provides cross-sectional nationally representative surveys of children and adolescents aged 11-16y based on self-reported data and questionnaires. Analysts of the HBSC survey for 2001-2 reported enormous variation (3-34%) in the prevalence overweight (including obesity) across the 35 countries and regions included in the 2001-2 survey. For Europe the highest prevalence is reported for the UK regions, followed by Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal and Spain (Mulvihill et al, 2006). The smaller 1997-8 survey (involving 13 European countries) reflects the same pattern, with highest rates reported for Ireland, Greece and Portugal (Lissau et al 2004).

The HBSC surveys for Greece, as for most other countries, show marked gender differences, with the prevalence of overweight and obesity being much higher in adolescent boys. Comparative analyses by gender with the WHO Eur-A3 group of countries shows prevalence of overweight and obesity among 15y boys in Greece (20.3% and 2.7% respectively) to be higher than the Eur-A average of 13.1% overweight and 2.5% obese, whereas prevalence among 15y girls in Greece (7.5% overweight and 1.1% obese) was somewhat lower than the Eur-A average of 7.6% overweight and 1.5% obese (WHO 2006).

3 The 27 European countries with very low child mortality and very low adult mortality, designated Eur-A by WHO comprise: Andorra, Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, San Marino, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. However, data for most indicators are unavailable for Andorra and Monaco. Therefore, unless otherwise indicated, averages for Eur-A refer to the 25 countries for which data are available.

9

For 2001-2, prevalence of overweight (including obesity) in 13y and 15y boys was 20.3% and 23% respectively, compared with 12.1% and 8.6% in 13y and 15y girls respectively. Similarly, detailed analyses available for the 1997-8 survey in Greece, which involved 4299 children and adolescents, show 9.1% of all girls and 21.7% of all boys classified as overweight, with corresponding values for obese girls and boys of 1.2 and 2.5% respectively (Karayiannis et al, 2003).

A second major recent study examining the prevalence and trends in childhood obesity is the widely cited IOTF comparative review of a number of surveys conducted in European countries using direct measurement methods (Lobstein et al, 2004; Lobstein and Frelut, 2003). This report showed the highest prevalence (>30%) of combined overweight and obesity among children aged 7-11y in the Mediterranean South: Italy, Malta, Spain, Greece and Cyprus. Among adolescents (14-17y) in these Mediterranean countries the incidence of overweight is much lower (~20%), comparable to reported rates for adolescents in Britain, but still higher than their counterparts elsewhere in Europe.

For Greece the IOTF data are derived from two regional studies: (a) a cross-sectional survey conducted in 2001-2 in the city of Thessaloniki, Northern Greece (Krassas et al 2001), and (b) a longitudinal study in Crete initiated in 1992, involving (2) smaller cohorts of school children (263 boys and 278 girls) from 6y to 16y (Manios et al 2002; Kafatos et al 2005). Figure 4 compares the available prevalence data from the Thessaloniki survey (n= 2,458), a recent evaluation of epidemiological data available for children and adolescents in Crete (n=1,209) (Linardakis 2005) and also the national survey data recently made available by the HMAO (n=18,045)(HMAO 2004). All studies use school cluster sampling and prevalence rates are derived from direct measurement data.

FIGURE 4: Prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents in Greece according to 3 (direct measurement) surveys

6,9

11,7 12,7

2926,6

20,7

27,9

25,3

11,2

7,610 9,7

6,58,9

13,7

3,74,9

16,3

11,1

25,3 25

12,5

20,1

1311,4

4,77,2

13,8

53,6

6,3

1,5

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

HMAO 2-6yrs

Crete 3-6yrs HMAO 7-12yrs

Crete 7-12yrs

Thessaloniki6-10yrs

HMAO 13-19yrs

Crete 13-18yrs

Thessaloniki11-17yrs

Boys Overweight Boys Obese Girls Overweight Girls Obese

[Data in Appendix Table A3]

10

The high prevalence of overweight and obesity shown for very young children <6y in both the HMAO and Crete studies (18-19% in boys and 16-21% in girls) is supported by available data from a recently conducted national survey of infants and pre-school children (n=2514), the Greek Infant Nutrition Survey (GINS) (Manios et al 2005). This study reports a progressive increase with age in the prevalence of overweight (including obesity) from 1-2y to 4-5y, from 11.6% to 18.3% in boys and from 12.5% to 17.8% in girls. Interpretation of this worrying data is complicated by the fact that survey samples include only those attending nurseries and kindergartens. As it stands, given the evidence of morbidity tracking into adulthood, it is serious cause for concern. The HMAO data show the prevalence of obesity lessening with increasing age for both genders to 8.9% for boys and 3.6% for girls in the 13-19y age band, while the prevalence of overweight increases to 20.7% in boys compared to 12.5% for girls. The Thessaloniki data also show a higher prevalence of obesity in the 6-10y age group compared with 11-17y boys and girls. By contrast, the Crete data show a steady increase in the prevalence of obesity among adolescent boys, and a decline only for teenage girls. These indications of alarmingly high rates of obesity are reinforced by analyses of waist circumference (WC) percentiles of children of Crete aged 3-16 y (n=5321) based on data from 3 longitudinal and 4 cross-sectional studies (Linardakis et al 2006), which indicates that the prevalence of abdominal obesity (WC >90th percentile) in boys and girls in Crete is on a par with the USA. The available data thus suggest significant regional variations in the prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents in Greece. ‘North/south’ regional variations (in growth curves) have been documented in Italy (Cacciari et al 2002). Whether the variations observed between studies in Greece to date are a function of study design or measurement sensitivity or socio-demographic factors impacting on regional susceptibility to obesity has yet to be determined. Similar reservations apply to available data on gender and age-related trends. There is, nonetheless, consistent evidence indicating a pattern of high and rising rates of overweight and obesity starting in infancy, with higher levels of overweight and obesity among children compared to adolescents. There is also converging evidence indicating that the prevalence of obesity as defined by BMI is consistently higher in adolescent boys compared to girls. 1.3 Conclusion Despite the piecemeal and fragmented nature of existing survey data in Greece, there is no doubt that the problem of overweight and obesity among adults and children in Greece is serious and appears to be getting worse. The rapidity of this development in Greece within the space of less than a generation presents an enormous public health challenge. Yet to channel concern into effective policy requires reliable and comparable public health indicators. The IOTF (2005) call for adequate monitoring and surveillance systems to ensure realistic assessment of the prevalence and trends in the obesity epidemic has a particular urgency in Greece. It is, in short, a critical requirement for sound health policy and effective policy interventions.

11

Summary of main points in section 1

Greece is regularly shown to top the charts of international and European ‘league tables’ of obesity prevalence among adults and children.

Existing survey data indicates that the problem is serious and appears to be getting worse. Conservative estimates are that 1 in 5 men and 1 in 6 women in Greece are obese and, in

addition, that approximately half the men (2.4m) and one-third of the women (1.4m) in Greece are overweight.

Albeit fragmentary, for children there is consistent evidence pointing to a pattern of high and rising rates of overweight and obesity starting in infancy; higher levels of obesity in children compared with adolescents; and a higher prevalence of obesity among adolescent boys compared with girls.

The rapidity of these developments presents enormous public health challenges. Not least of these is the need for adequate monitoring and surveillance systems to

accurately assess the dimensions of the problem and also to enable effective policy responses.

12

Section 2 Estimated Costs of Obesity As the prevalence of overweight and obesity increases, concern about the association with morbidity and premature mortality is also increasing. Estimates of the burden of disease due to obesity and the related direct and indirect economic costs are focusing attention on obesity as a public health problem requiring the attention of policy makers and health planners, rather than simply the concern of the individuals affected. This section considers these estimated human and financial costs and how they may be impacting on the health profile and pockets of the Greek population. 2.1 Human Costs: Health Risks and the Burden of Disease Overweight and obesity are associated with adverse metabolic effects on blood pressure, cholesterol, triglycerides and insulin resistance: a clustering of complications known as the metabolic syndrome. As such excess weight gain, and particularly abdominal obesity, is also one of the key risk factors for a number of chronic diseases. A vast body of evidence is accumulating on the pathology and health consequences of obesity among children and adults. Recent reviews (WHO, 2002; Lobstein et al, 2004) identify the non-fatal but debilitating health problems associated with obesity to include respiratory difficulties (sleep apnoea and asthma), chronic musculoskeletal problems (including osteoarthritis), and endocrine disorders (including polycystic ovarian syndrome and infertility). The more life-threatening illnesses associated with obesity are:

- cardiovascular diseases (CVD), including coronary heart disease, and cerebrovascular diseases (hypertension, stroke);

- non-insulin-dependent diabetes (NIDDM or type 2 diabetes); - certain cancers, especially the hormonally related (endometrial, breast) and large-

bowel (colon) cancers, and - gallbladder disease.

All these conditions become more prevalent with age and are also more prevalent among overweight people. This translates into an escalation of the burden of ill-health from obesity with age (Lean, 2000; WHO 2002). Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as these are multi-causal and now account for the bulk (>80%) of morbidity and mortality in most developed countries, including Greece. Quantifying the links between obesity and the diseases with which it is associated therefore present complex methodological challenges. That is, there are inherent (statistical) uncertainties due to the number of assumptions needed to calculate the relative risk of obesity as a causal/contributory factor, and also due to the limited nature of the data available (prevalence, morbidity, mortality) for estimating the burden of disease attributable to overweight and obesity4. In terms of relative risk: Table 2.1 presents the best available estimates of the extent to which obesity increases the risks of developing major chronic diseases relative to the non-obese population. These estimates, compiled for the UK National Audit Office, are based on

4 The attributable fraction shows that the burden of disease caused by any risk factor is a function of the prevalence of that risk factor and the magnitude of its causal association with disease, expressed as relative risk. The methodological issues involved in these calculations are reviewed briefly by Mark (2005) and in detail by Mathers & Loncar, 2005.

13

a comprehensive review of international (primarily North American) studies and give a broad indication of the strength of the association between obesity and the main disease types (NAO, 2001). In addition to increasing the risk of ill-health, obesity increases the risk of mortality at any given age. Evidence suggests that for young adults in general the risk of premature mortality (<65y) for someone with a BMI of 30 is about 50% higher than that of someone with a healthy BMI (20-25), and with a BMI of 35 the risk is more than doubled (ibid). There is also a link between mortality risk and duration of overweight; those who have been overweight for the longest are at highest risk (ibid).

Table 2.1 Estimated increased risk for the obese of developing associated diseases taken from international studies

Disease Relative risk Women

Relative risk Men

Type 2 Diabetes 12.7 5.2 Hypertension 4.2 2.6 Myocardial Infarction 3.2 1.5 Cancer of the Colon 2.7 3.0 Angina 1.8 1.8 Gall Bladder Diseases 1.8 1.8 Ovarian Cancer 1.7 - Osteoarthritis 1.4 1.9 Stroke 1.3 1.3

Source: National Audit Office, 2001 (UK) In terms of mortality: WHO analysts attribute 9.6% of deaths among men and 11.5% of deaths among women in developed economies specifically to overweight (WHO 2002). Other studies suggest somewhat lower estimates – eg. that 1 in 13 deaths in the EU are considered likely to be related to excess weight (Banegas et al 2003). Recent analyses in the US of mortality attributable to obesity have produced very wide-ranging figures5, and underline the point that small variations in estimates of relative risk can lead to substantial differences in estimates of mortality attributable to excess weight. While imperfect, efforts to determine attributable fractions do provide useful indicators as to the serious dimensions of the problem. For example, recent analyses in the US estimated that excess weight (BMI ≥25) and physical inactivity (<3.5 hours exercise/week) together could account for 31% of all premature deaths, 59% of deaths from cardiovascular disease, and 21% of deaths from cancer among non-smoking women (Hu et al, 2004). In terms of the total burden of disease: The best available impact indicator to date is the WHO analyses of the burden of disease attributable to selected leading (dietary and lifestyle) risk factors, measured in disability-adjusted-life years (DALY). This is a summary measure used by WHO analysts that combines the estimated impact of illness and disability as well as mortality on population health. As indicated in Table 2.2, for developed economies such as

5 Flegal et al (2005) estimate that there were about 112 000 obesity-attributable deaths in the US in 2000, far lower than the 414 000 estimated by Mokdad et al for the same year (and the 280 000 estimated by Allison et al for 1991). Moreover, as Mark (2005) points out, the assessment of obesity-related disease is further complicated by the issue of statistical uncertainty. Few studies to date include a formal calculation of confidence intervals(CIs), but the 95% CI provided by Flegal et al around the estimate of 112 000 deaths attributable to obesity ranges from 54 000 to 170 000 i.e greater than a three-fold difference reflected within the range. As Mark (2005) concludes, these studies and their disparate findings highlight the importance of continuing to develop more rigorous approaches for estimating obesity-attributable deaths.

14

Greece, 7.4% of the total burden of NCDs (in DALYs) is considered attributable specifically to overweight (6.9% for men and 8.1% for women) (WHO 2002). There is evidently an inter-relationship between the WHO risk factors. For example, elevated blood pressure and elevated cholesterol, each of which is an independent risk factor for CVD, can also be caused or aggravated by weight gain. According to these estimates, overweight and its co-morbidities together exceed the burden of ill-health linked to tobacco and, with dietary inadequacies and physical inactivity, account for approximately one-third of the total disease burden (in DALYs) in developed economies.

Table 2.2 Burden of disease measured in DALYs (%) attributable to selected risk factors

Risk factors Total DALYs (%)

Tobacco 12.2 Blood pressure 10.9 Alcohol 9.2 Cholesterol 7.6 Overweight 7.4 Low fruit and vegetable intake 3.9 Physical inactivity 3.3 Illicit drugs 1.8 Unsafe sex 0.8 Iron deficiency 0.7 Source: WHO, 2002

2.2 Morbidity and Mortality in Greece At first glance, the rising prevalence of overweight and obesity in Greece has not had a readily discernible impact on the health profile of the population. Indeed, along with other countries in Southern Europe, Greece continues to enjoy an enviable reputation for longevity and health that is associated with the beneficial health properties of the Mediterranean diet (to be discussed in Section 3). As such, commentators continue to point out that in Greece and other Mediterranean countries the absolute risk of obesity-related diseases such as cardiovascular disease is among the lowest in Europe (Kromhout, 2001; Haftenberger et al, 2002). This apparent paradox warrants a closer look at the population health data. Life expectancy at birth has continued to increase steadily in Greece and now stands at 75.8y for men and 81.1y for women (WHO 2006).6 Absolute gains in the last 20 years (~3years) have been smaller than other EU countries. Although male life expectancy (at birth and at 65y) in Greece continues to rank among the highest in Europe, women’s life expectancy, from well above the EU average at the beginning of the 1970s, has remained at or below the EU average from the 1980s onwards. This is attributed primarily to relative deterioration in women’s life expectancy at 65y (with the SDR for CVDs in women in Greece >65y being markedly higher than the EU average). The net effect, as shown in Figure 2.1, is that Greece has lost its leading position and since 1995 life expectancy at birth has been at or below the EU-15 average, whereas LE at 65y has been below the EU-15 average since the late 1980s. 6 According to WHO estimates Greeks, on average, can expect to be healthy for about 90% of their lives. On average Greeks lose 7.4y to illness – the difference between LE and healthy life expectancy (HALE). Since women live longer than men, and the likelihood of deteriorating health increases with age, women lose more healthy years (8.2y) than men (6.7y) WHO (2003):

15

Greece EU members before May 2004 EU members since May 2004

Source: WHO/Europe, European HFA Database, January 2006 The extent to which this relative deterioration in LE is associated with the obesity epidemic is a matter of conjecture (considering the numerous factors affecting LE as well as the lack of evaluative studies in Greece). Given the evidence of increased risk of mortality associated with obesity, an effect cannot be ruled out. It is worth noting in this respect that in the UK the average loss of life attributable to obesity has been estimated to be over two years on current UK life expectancy statistics and is expected to rise to over five years as healthy life expectancies increase faster for normal weight than for obese people (UK Department of Health 2005). As in other European countries, cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the biggest single cause of death, accounting for 49% of all deaths in Greece in 2001 (WHO, 2006). CVDs are associated with age in that nearly nine out of ten deaths of this type occur in persons aged 65y or over (Eurostat 2004). As shown in Figures 2.2 and 2.3, the last 25-30 years have witnessed a relative deterioration in mortality rates in Greece from all CVDs from among the lowest in Europe to around the EU average for ischaemic heart disease, to well above the EU average for cerebrovascular diseases (hypertension, stroke). CVD mortality rates in Greece are now considerably higher than in other Mediterranean populations (Italy, Portugal, Spain). Specifically: premature mortality rates (<65y) and standardized death rates (SDRs) for all ages due to ischaemic heart disease have shown negligible changes since the 1980s in Greece, in contrast with the marked downward trend in most other European countries. SDRs for cerebrovascular diseases do show a downward trend, which approximately parallels trends elsewhere in Europe, but at observably higher rates.

Fig 2.1a Life expectancy at birth Fig 2.1b Life Expectancy at 65y

16

Fig 2.3b SDR, Cerebrovascular diseases, all ages per 100.000

Greece EU members before May 2004 EU members since May 2004 Source: WHO/Europe, European HFA Database, January 2006

Greece EU members before May 2004 EU members since May 2004

Source: WHO/Europe, European HFA Database, January 2006 Cancers are the second main cause of death in Greece, accounting for 25% of all deaths. As shown in Figure 2.4, overall cancer mortality rates are consistently below the EU average, and this also applies to cancers linked with obesity (female breast cancer and colon cancer). The notable exception is death rates for cancer of the lung, which have been rising steadily for both sexes and are well above the EU average. This is linked directly with the very high prevalence of cigarette smoking in Greece (>33% adults) (OECD 2005).

Fig 2.3a SDR, Cerebrovascular diseases, 0-64y, per 100.000

Fig 2.2a SDR, Ischaemic Heart Disease, 0-64y, per 100.000

Fig 2.2b SDR, Ischaemic Heart Disease, all ages per 100.000

17

Greece EU members before May 2004 EU members since May 2004

Source: WHO/Europe, European HFA Database, January 2006 Interpreting changes in mortality rates as functions of risk factors or the features of health care systems requires caution, including consideration of the reliability and comparability of death certification practices (Eurostat, 2004). Even so, the data warrants serious concern insofar as trends in CVD in Greece – the primary killer and also the leading cause of death among the obese – do not match the decreasing trend in age-adjusted cardiovascular disease mortality observed in the USA and in most other Western European countries. Recent analyses of secular trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors according to BMI for US adults (based on NHANES surveys from 1960-62 through to 1999-2000) concluded that, with the important exception of diabetes, the prevalence of high cholesterol, high blood pressure and smoking have declined significantly over the past 40 years in all BMI groups (Gregg et al, 2005). The NHANES analysts noted that although obese persons still have higher risk factor levels than lean persons, the levels of these risk factors are much lower than in previous decades (ie obese persons in the US now smoke less and have lower cholesterol levels and lower blood pressure). These changes in risk factors have been accompanied by increases in lipid-lowering and anti-hypertensive medication use, particularly among obese persons (ibid). These results, which indicate that the relationship between obesity and its co-morbidities is not necessarily constant, are consistent with the increase in life expectancy and the declining mortality rates from ischaemic heart disease in the USA (Mark 2005), despite the increasing prevalence of obesity, and may have a bearing on the mortality rate in Greece. For Greece, the relatively static mortality rates for ischaemic heart disease and slacker downward trend in cerebrovascular disease mortality have been accompanied by an escalating burden of clinical care, as indicated by hospital discharges associated with these primary cardiovascular diseases (Figure 2.5). Moreover, an increasing number of cardiovascular patients is expected because of the ageing of the population (Kromhout, 2001), and this is likely to be compounded by age-related trends in obesity and its co-morbidities. Available evidence on the prevalence of CVD risk factors indicates that a high proportion of adults in Greece are at risk (Pitsavos et al, 2003; Efstrapopoulos et al, 2006; Gikas et al 2004). The best available nationally representative survey, the MetS-Study

Fig 2.4a SDR, Malignant Neoplasms, 0-64y, per 100.000

Fig 2.4b SDR, Malignant Neoplasms, all ages, per 100.000

18

(Athyros et al, 2005), reports an age-standardized prevalence of the metabolic syndrome* of 23.6% among Greek adults (with rates being similar in men and women). As to be expected, prevalence increases with age in both sexes (4.8% in the 19-29y age group and 43% for those over 70 years old), and the most common abnormalities for both men and women are abdominal obesity and hypertension. Based on the 2001 Census, the Met-S analysts estimate that about 2.3 million Greeks may have the metabolic syndrome (ibid).

Greece EU members before May 2004 EU members since May 2004

Source: WHO/Europe, European HFA Database, January 2006 Better health care and medication can be expected to mitigate the consequences of CVD in terms of morbidity and premature mortality, but it is as yet unclear whether such gains will be offset by the increasing prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents. That is, there is concern that younger age of onset of obesity may result in longer duration of obesity throughout life, which may increase obesity-related morbidity and mortality (Mark, 2005). Existing evidence indicates that cardiovascular risk factors are now being routinely detected among Greek school-children and adolescents, with worrying implications for their future health (Magkos et al,2005; Bouziotas et al, 2004; Manios et al 2004; Manios et al 2005). Particular concern is focusing on the appearance of type 2 diabetes, previously known as adult-onset diabetes, among obese children and adolescents. Non-insulin-dependent / type 2 diabetes, which is rapidly becoming one of the major non-communicable diseases in Europe, is arguably the most insidious medical consequence of obesity. As one expert analyst has aptly summarized, it is increasingly common, has serious complications, is difficult to treat, reduces life expectancy by 8-10 years and is expensive to manage (Astrup, 2001). It is estimated that approximately 85% of people with diabetes are Type 2, and of these over 90% are overweight (WHO 2006), In turn, the metabolic abnormalities underlying type 2 diabetes predispose to hypertension and CVD.

* Metabolic syndrome is considered present with at least 3 of the 5 identified risk factors; i.e. abdominal obesity, hypertriglyceridaemia, low HDL-cholesterol, high blood pressure and high fasting glucose.

Fig 2.5a Hospital Discharges, Ischaemic Heart Diseases per 100.000

Fig 2.5b Hospital Discharges, Cerebrovascular diseases per 100.000

19

For Greece, the most recent estimated prevalence for 2003 is 6.1%, projected to rise to 7.3% by 2025 (IDF 2003, EC Commission 2006). WHO estimates in terms of numbers point to 853,000 affected in 2000 rising to over one million people (1,077,000) in Greece by 2030 (WHO 2006). The recent ATTICA Study, however, indicates that the prevalence of type 2 diabetes already exceeds predictions at 7.8% of men and 6% of women (Pitsavos et al, 2003). Moreover, as shown in Figure 2.6, there is a steep age-related increase in prevalence in men and women over 55 years of age. Fig 2.6 Diabetes Prevalence in Greece by age group

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

45%

18-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65-74 75-89

Men (n=1416)

Women (n=1407)

Source: ATTICA Study data as supplied to the WHO (2006)

The myriad other disabilities and debilitating conditions associated with obesity are recognized as having a strong negative impact on health status and quality of life, but there is insufficient data available to assess these human costs. As it stands, the current and projected burden of disease in Greece caused by the primary life-threatening conditions associated with obesity leave scant room for complacency.

20

2.3. Health Care Costs As shown in Figure 2.7, developments in the health profile of the Greek population have been accompanied by rising health care costs, which in 2003 totalled 9.9% of GDP (OECD 2005). Public expenditure accounts for just over half of total health care expenditure in Greece (51.3% in 2003) (OECD 2005), making the proportion of health care costs borne by private expenditure among the highest in Europe (WHO 2006). Pharmaceutical expenditure is also relatively high, accounting for ~16% of total health expenditure (OECD 2005).

Greece EU members before May 2004 EU members since May 2004

Source: WHO/Europe, European HFA Database, January 2006

Growth in health spending can be attributed to several factors (ibid). Advances in the capability of medicine to prevent, diagnose and treat health conditions are a major factor driving health cost growth. Population ageing also contributes to the growth in health spending, as does obesity. Estimates from the United States indicate that the cost of health care services is 36% higher and the cost of medications 77% higher for obese people than for people of normal weight (Sturm, 2002), and that these costs grow disproportionately large for the severely obese (Andreyeva et al, 2004; Raebel et al, 2004). As regards the cost burden at national level, reflecting the lack of authoritative evidence on the prevalence and human costs of obesity in Greece, the extent to which total health care costs can be attributed to obesity is not known. Estimates made for other countries, however, indicate that they may be substantial. Recent analyses by the UK National Audit Office (NAO 2001) lists the direct costs of obesity as arising from medical consultations, including hospital admissions, and the cost of drugs prescribed (a) for treating obesity itself and (b) for treating diseases attributable to obesity. Using 1998 figures for England, the NAO estimated the direct costs of treating obesity to be £9.4 million at 1998 prices, mainly due to the cost of consultations with general practitioners. The cost of treating diseases attributable to obesity was estimated to be £469.9

Fig 2.7 Total health expenditure as % of Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

21

million, adding to a total of about 1.5% of National Health Service expenditure in that year. The most significant cost drivers are hypertension, coronary heart disease, and Type 2 diabetes, followed by osteoarthritis and stroke (ibid). The probability that these figures underestimate the direct costs was acknowledged by the NAO, since it excludes potentially high costs such as care for obesity-related stroke patients (ibid). A review made by the UK PorGrow analysts (Millstone & Lobstein, 2006) also points out that these estimates are low compared to the findings of studies undertaken in other countries where, as shown in Table 2.3, the direct costs of obesity have been estimated to lie between 2% and 8.5% of national health care budgets. [If this range applied in Greece, the direct costs of treatment for obesity and its consequences would be between 150 - 853 million euros at 2000 figures*]

Table 2.3 Estimates of the direct costs of obesity to National Health Services.

Prevalence of obesity (BMI>30) Country Year of

estimate

Proportion of total healthcare expenditure

due to obesity At time of estimate

Latest available

USA 1999 8.5% 30.5% 30.5%

USA 2000 4.8% 30.5% 30.5%

Netherlands 1981-89 4.0% 5.0% 10.3%

Canada 1997 2.4% 14.0% 13.9%

Portugal 1996 3.5% 11.5% 14.0%

Australia 1989/90 >2.0% 10.8% 22.0%

England 1998 1.5% 19.0% 23.5%

France 1992 1.5% 6.5% 9.0% Source: House of Commons 2004 as cited by Millstone & Lobstein (2006)

Given that there is a time lag of several years between the onset of obesity and related health problems, rising health care costs are to be expected, particularly in view of the rising prevalence of childhood obesity. An indication of trends is provided by a US study of obesity-associated hospital costs for children and adolescents (6-17y), which showed a three-fold increase over a twenty-year period (1979 – 1999) (Wang & Dietz, 2002). 2.4 Other Economic Costs Evaluation of the indirect costs associated with obesity rely on calculations of lost earnings and/or lost production arising from (a) the premature death of active members of the workforce and (b) from days of medically certified sickness absence attributable to obesity and its consequences. There are currently no such estimates available in Greece. The NAO (2001) evaluation for England for 1998 indicates that these indirect costs might be enormous: an estimation of lost earnings of £2,149 million, of which 61% was due to sickness absence attributable to obesity, and the remainder to premature mortality. Moreover, the NAO analysts considered the amount of sickness absence attributed to obesity *Calculations based on Eurostat (2002) compilations of total health expenditures for 2000 of €10 032 million (8.3% of GDP). Calculations derived from more recent OECD (2005) figures for GDP for 2003 of $225,8 billion USD, and total health expenditure as 9.9% of GDP, give a higher range: 300 million - 1.9 billion USD at 2003 rates.

22

(over 18 million days medically certified absence) to be an underestimate, as it excludes both self-certified and uncertified sickness absence, and takes no account of sickness due to diseases for which the proportion of cases attributable to obesity cannot be quantified, e.g. back pain (NAO, 2001) There are other financial and intangible costs of obesity that are unaccounted for, including the social and psychological effects associated with being obese. For example, excess bodyweight is linked to less chance of finding a marriage partner or a job, and of being promoted, particularly for women (Viner & Cole, 2005). Overweight people are likely to be on lower earnings (perhaps reducing the lost-days-of-work costs) but are more likely to suffer low self-esteem and depression. Psychiatric problems, especially depression, are the largest single cause of disability-adjusted-life-years (DALYs) in developed economies 7 and are also a major cost to the health services and a cause of lost productivity (Millstone & Lobstein, 2006). 2.5 Conclusion Obesity and its co-morbidities are associated with substantial human costs in the form of chronic disabilities, illnesses, and premature mortality. It also has serious financial costs for national health services and for the economy. Data limitations mean that estimation of the burden of disease and the accompanying economic costs attributable to obesity in Greece are matters of conjecture. Concern is, however, warranted by the relative deterioration in life expectancy and by trends in the major diseases associated with obesity – notably cardiovascular diseases and diabetes. (In particular, trends in CVD mortality rates do not match the decreasing trends observed in other Western European countries.) These developments in the health profile of the population have been accompanied by an escalating burden of clinical care. Evidence suggests that many of the risks and complications of obesity are reversible or can be mitigated by even modest weight losses (Astrup, 2001). While the success rate in treating obesity is relatively low (IOTF 2005), there is evidence that adverse consequences /co-morbidities are increasingly being controlled or alleviated through medication and improvements in health care. In view of the rising prevalence of obesity in Greece, there is a pressing need to assess current and projected demands on the health services and respond accordingly. Apart from collateral strategies for those affected, however, the principal challenge lies in halting the upward trend, particularly among children.

Summary of main points in section 2 The various cost dimensions of obesity indicate a strong economic rationale for public

policy action. The population health profile of relative longevity and low rates of non-communicable

diseases has co-existed paradoxically with the rising prevalence of obesity. Recent trends in morbidity and mortality data, particularly for cardiovascular diseases

and type 2 diabetes, indicates that this pattern no longer holds. Rising morbidity rates have been accompanied by escalating health care costs. Reliable estimates of the current and projected economic and health costs of obesity in

Greece are needed to inform policy actions.

7 The WHO estimates that in Greece neuropsychiatric conditions are the second leading cause of DALYs for men (19.5% of total DALYs compared with 24.9% attributed to CVDs) and on a par with DALYs attributed to CVDs for women (24.8%) (WHO 2003).

23

Section 3 Trends in Food Consumption and Physical Activity

3.1 Causal Influences It is generally accepted that weight gain is regulated by gene-environment interactions. That is, obesity develops on the background of a genetic predisposition, and increased susceptibility may occur through interaction with other factors, e.g. fetal programming (WHO,2000; Astrup 2001).The expression of genetic susceptibility, however, depends on environmental factors. Reviews of determinants indicate a high level of evidence and consensus in this respect for the role of behavioural factors, such as low levels of physical activity and high intakes of energy-dense foods, and also some food composition factors, such as high fat content, low fibre content. There is less robust evidence but significant interest in potential determinants (eg breastfeeding, the glyceamic index of foods) and a reasonable consensus that certain elements of the environment are important (eg the built environment, advertising of food to young children, parental and family factors, and the school environment). (WHO 2003; Swinburn et al 2004). Reduced to its most basic equation, excessive weight gain develops in susceptible individuals when energy intake exceeds energy expenditure or, as one analyst aptly put it, ‘when they are exposed to an abundant availability of energy-dense, high fat, palatable foods and a lifestyle characterized by physical inactivity’ (Astrup, 2001). Although many weight-control measures are targeted at individuals, a simplistic approach which focuses exclusively on the behavioural choices of individuals is fraught with moral connotations (gluttony-sloth) and the accompanying risk of stigmatization. More fundamentally, it impedes our understanding of how the rising prevalence of obesity has occurred in our society. The public health perspective as voiced by the WHO and IOTF looks to causal pathways: profound economic and social developments affecting behavioural patterns of communities over recent decades. A ‘causal web’ framework developed by an IOTF working group illustrates the societal influences on obesity prevalence (Appendix Figure A3.1). It points to the complex links between economic growth, technological developments, urbanization and globalization of food markets which are driving changes at regional and local level in areas such as agriculture, health and welfare, education, trade and commerce and thereby affecting food availability, eating habits and habitual physical activity. These processes are complex, dynamic and ongoing (Swinburn et al, 2005). There are, in short, a large number of influences ‘upstream’ affecting an individual’s food choices and energy expenditure which, as the WHO points out, calls for a balance between individual and population-wide approaches, and between education-based and multi-sectoral environmental interventions (WHO 2003). An assessment of policy options for effective interventions requires an understanding of changes in food consumption and physical activity patterns which have fueled the rising prevalence of obesity. This section looks at available data on the trends in Greece.

24